The NYPD lost 23 of its own in the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center. Since the attack, another 29 have died from health issues related to their exposure to Ground Zero contamination and hundreds more have been granted 9/11 health-related disability. This week, supporters of the landmark Federal 9/11 Health and Compensation Act brought the badges belonging to the 29 NYPD officers to the nation's capital.

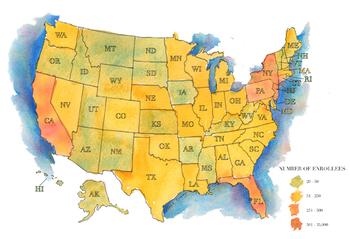

Also known as the Zadroga Bill, named for one of the NYPD officers who died after the attack from 9/11 health related casues, the legislation would fund health care for all the first responders and volunteers as well as eligible Manhattan residents. The 9/11 Health registry so far is tracking the ongoing health if some 71,000 people who had some exposure to Ground Zero contamination.

Advocates say they hope to get the 9/11 health bill through the Senate in this current lame duck session of Congress. They still need one or two Senate Republicans to vote for the bill but say they have the vote of at least one Repulican, incoming Illinois Senator Paul Kirk, who voted for the bill as a member of the House. The House has passed the bill earlier this year.

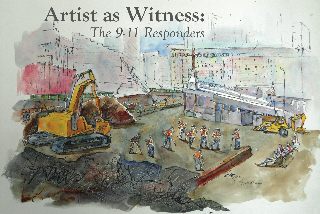

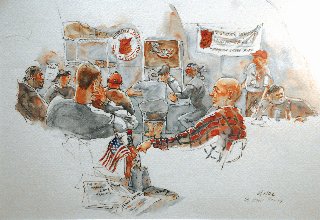

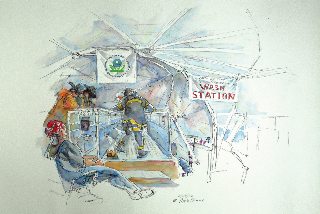

Along with the badges, the bill's backers put a series of paintings on display in the Russell Senate Office Building rotunda that depict the challenging Ground Zero Recovery effort that went on for months.

Aggie Kenny makes her living as a courtroom artist. At a recent showing of her work depicting the Ground Zero first responders at the NYPD Museum, Kenny said she simply wanted to be a witness with an unflinching eye.

"It had everything to do with just watching and just immediately copying down what I saw just as I suppose a reporter would in their notebooks," Kenny said.

Kenny is used to sketching the world's most sinister bad guys as they pass through the federal courts of Lower Manhattan. Yet after September 11, she was moved to approach the Salvation Army for a very different kind of assignment — capturing in ink and waterscolors the action of the recovery effort. Her artistic documentation took place in March and May of 2002.

"I was very used to working with a lot of hubris around and people watching and I can focus on my work and be unaffected by the surrounding activity," said Kenny.

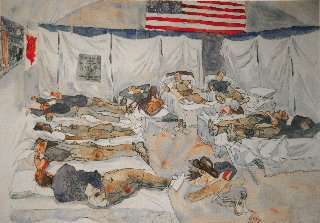

She recalls a massive tent on the site first responders dubbed the Taj Mahal where they would go to eat and sleep. "When I first walked in to the Taj, I had the sense of a cathedral almost and I was struck by the quiet," recalled Kenny. "Everything was quiet and almost gentle."

Kenny's most poignant recollections and images are of first responders when they weren't working.

"I saw the personal side of these responders when I went and watched them sleeping," said Kenny. "They would come in from the pile. These men would just literally collapse on the cots and there were teddy bears by them. Their shovels and all their equipment were on their sides and there were little posters on the wall from Brownie troops and children from around the country."

For years, her 9/11 work remained packed away in her home and garage. Kenny knew she didn't want to sell it, but it was a fellow courtroom artist who gave her the idea that this work could help make the case in Washington for passage of the 9/11 First Responder Health bill. And now, installed in the Capitol along with the shields of 29 police officers who died from exposure to Ground Zero contamination, is "Artist as Witness: The 9/11 First Responders."

Catherine McVay-Hughes is with Community Board One in Lower Manhattan. At the showing at the police museum, she but Kenny's work in an important historical context.

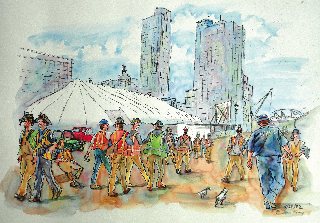

"This picture here is dated May 2002. We knew that the dust, in huge quantities of dust in the air was an issue," McVay-Hughes says. "Look at these workers, these first responders raking through the rubble, looking for evidence, looking to see what they could find. None of them are wearing any protective gear at all," said McVay-Hughes.

McVay- Hughes said the value of Kenny's work is not just commemorative. She says the images are sad to look at because they depict just how ill-prepared the first responders remained even months after the attack.

"And also really important here is you see them working and sleeping and eating near the burning fires," she said.

McVay-Hughes said this week's display in the Russell Building, which was organized by U.S. Senator Kirsten Gillbrand, is a graphic reminder of the human toll of the recovery effort. The timing of this display is strategic.

"Anyone who will be voting on the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act will have to walk by the 29 shields of the police officers that have died in the line of duty due to their exposures to 9/11," reason McVay Hughes.

Artist Kenny is gratified that the work that she put away for years is now surfacing at a critical time. "No way did I ever think when I was at Ground Zero that my sketches could somehow help the responders, " she says.