Malcolm Bowman, an oceanography professor from Stony Brook University in Long Island, recently stood at the snow-covered edge of the Williamsburg waterfront and pointed toward the Midtown skyline. "Looking at the city, with the setting sun behind the Williamsburg Bridge, it's a sea of tranquility," he said. "It's hard to imagine the dangers lying ahead."

But that's his job.

He said that as climate change brings higher temperatures and more violent storms, flooding in parts of the city could become as routine as the heavy snows of this winter. We could even have "flood days," the way we now have snow days, he said. Bowman and other experts say the only way to avoid that fate and keep the city dry is to follow the lead of cities like Amsterdam and Saint Petersburg and build moveable modern dykes. Either that or retreat from the shoreline.

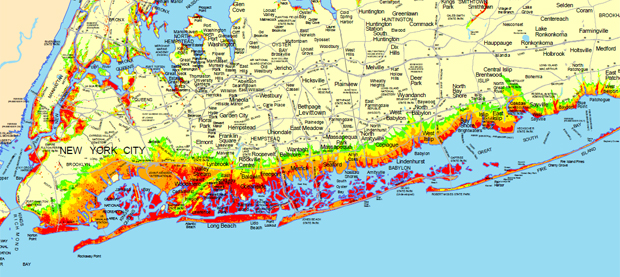

Higher sea levels will give severe storms much more water to funnel toward the city. Bowman pointed first north, then south, to depict surges of water coming from two directions: through Long Island Sound and down the East River and up through the Verrazano Narrows toward Lower Manhattan. The effect could be worse than anything seen before.

![]()

Neighborhoods vulnerable to storm surge (Courtesy of NYSEMO GIS)

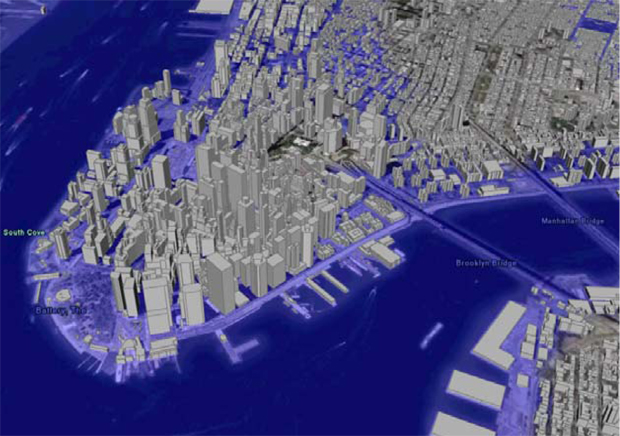

“Straight across the river, we could expect the FDR Drive to be underwater. We would expect the water lapping around Wall Street," he said. "We could see vital infrastructure, hospitals, sewage treatment plants, communication conduits all paralyzed by flooding with seawater, which is very corrosive.” (SEE IMAGE BELOW RIGHT)

The city got a glimpse of such destructiveness with the December Nor'easter of 1992, when massive flooding shut down the PATH train and the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. Again, in the summer of 2007, a flash storm dumped so much rain so quickly that most subways stopped running. Afterward, the MTA removed 16,000 pounds of debris from its tracks and spent weeks repairing electrical equipment.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s Panel on Climate Change said an increase in the number of such devastating storms is “extremely likely.”

John Nolon, a Pace University law professor with an expertise in sustainability law, said city officials have done a good job of at least describing the problem. “A lot of New York City is less than 16 feet above mean sea level," he said. "Lower Manhattan, some points are five feet above sea level. These areas are vulnerable and New York City knows it. Compared to other cities, which are only now beginning to wake up to this issue, I think New York City is much further ahead.”

But what to do?

David Bragdon, Director of the Mayor's Office of Long-Term Planning & Sustainability, is charged with preparing for the dangers of climate change. He said the city is taking precautions like raising the pumps at a wastewater treatment plant in the Rockaways and building the Willets Point development in Queens on six feet of landfill. The goal is to manage the risk from 100-year storms – one of the most severe. The mayor’s report says by the end of this century, 100-year storms could start arriving every 15 to 35 years.

Klaus Jacob, a Columbia University research scientist who specializes in disaster risk management, said that estimate may be too conservative. “What is now the impact of a 100-year storm will be, by the end of this century, roughly a 10-year storm,” he warned.

Back on the waterfront, Bowman offered what he said is a suitably outsized solution to this existential threat: storm surge barriers.

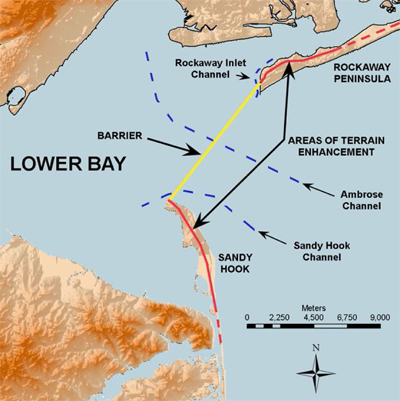

They would rise from the waters at Throgs Neck, where Long Island Sound and the East River meet, and at the opening to the lower harbor between the Rockaways and Sandy Hook, New Jersey. Like the barriers on the Thames River that protect London, they would stay open most of the time to let ships pass but close to protect the city during hurricanes and severe storms. (SEE IMAGE BELOW)

The structures at their highest points would be 30 feet above the harbor surface. Preliminary engineering studies put the cost at around $11 billion.

Jacob suggested a different but equally drastic approach. He said sea level rise may force New Yorkers to pull back from vulnerable neighborhoods. “We will have to densify the high-lying areas and use the low-lying areas as parks and buffer zones,” he said.

In this scenario, New York in 200 years looks like Venice. Concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have melted ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica and raised our local sea level by six to eight feet. Inundating storms at certain times of year swell the harbor until it spills into the streets. Dozens of skyscrapers in Lower Manhattan have been sealed at the base and entrances added to higher floors. The streets of the financial district have become canals.

“You may have to build bridges or get Venice gondolas or your little speed boats ferrying yourself up to those buildings,” Jacob said.

David Bragdon is not comfortable with such scenarios. He’d rather talk about the concrete steps he’s taking now, like updating the city’s flood evacuation plan to show more neighborhoods at risk. That would help the people living in them be better prepared to evacuate.

He said it's too soon to contemplate the "extreme" step of moving "two, three, four hundred thousand people out of areas they’ve occupied for generations," and disinvesting "literally billions of dollars of infrastructure in those areas." On the other hand: "Another extreme would be to hide our heads in the sand and say, ‘Nothing’s going to happen.’”

Bragdon said he doesn't think New Yorkers of the future will have to retreat very far from shore, if at all, but he’s not sure. And he would neither commit to storm surge barriers nor eliminate them as an option. He said what’s needed is more study—and that he’ll have further details in April, when the city updates PlaNYC.

Jacob warned that in preparing for disaster, no matter how far off, there's a gulf between study and action. "There’s a good intent," he said of New York's climate change planning to date. "But, you know, mother nature doesn’t care about intent. Mother nature wants to see resiliency. And that is questionable, whether we have that.”