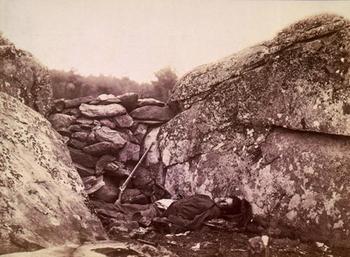

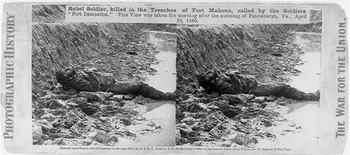

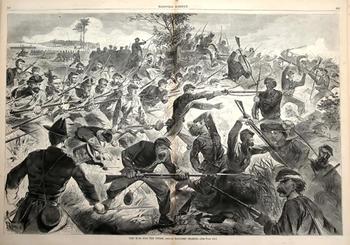

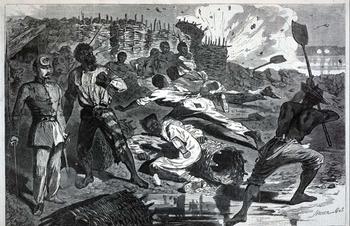

Many of the images we know of the Civil War come from the photos of Mathew Brady. Brady and his assistants recorded the rigidly posed generals and the battlefields scattered with bodies. But very few people at the time actually saw Brady's pictures – and those who did were horrified. Illustrators like Winslow Homer (later famous for his land- and seascapes) did things the photographers could not: take audiences right into the action, behind enemy lines, and up a tree with a sharpshooter. Produced by Studio 360’s Jonathan Mitchell.

Slideshow: Mathew Brady and Winslow Homer

Music Playlist

-

Graceland

Artist: Paul SimonAlbum: GracelandLabel: Warner Bros / Wea -

Expedition

Artist: Joseph TrapaneseAlbum: Indie - Music for Independent FilmLabel: Blue Bonsai Music