New York is a city of specialists from foodies to academics, laborers to shopkeepers. Every Wednesday, Niche Market takes a peek inside a different specialty store and showcases the city's purists who have made an art out of selling one commodity. Slideshow below.

This Niche Market was suggested by WNYC listener Brad Klein.

Retrofret

233 Butler Street

Brooklyn, NY 11217

When Mamie Minch was looking for a new steel guitar, she knew exactly what she wanted — an old one.

"I wanted something that could sound warm and really tiny and growly, and depending on how you held it and how you used it you could get a lot of different sounds out of it," said the Blues and American roots musician.

After two years of hanging out at Retrofret in Gowanus, Brooklyn, a shop specializing in vintage, rare and unusual fretted instruments, she got a call that the store had found her match. It was a 1937 National Duolian Resophonic with 14 frets, and to this day, four years later, she gets excited every time she picks it up.

That instrument was one of over 500 vintage pieces lovingly displayed in Retrofret's loft space, located on a nondescript block dominated by a sanitation truck repair shop. Customers have to ring a bell, walk up a flight of stairs and across part of a roof in order to enter the store.

Founder and owner Steve Uhrik, 56, got hooked on strings early. As a young kid one day he just picked up a mandolin in his house and began fiddling.

"I immediately started taking it apart to improve upon it," he said.

During high school, Uhrik honed his trade under the watchful eye of Sam Eisenstein, a master violin restorer whose shop was right next to Carnegie Hall.

He played in several bands, but his true interest was always instruments as objects, particularly historical ones, he said, his eyes resting a moment on the instrument display cases that once stood in Eisenstein's shop. Soon after graduating from Brooklyn Technical High School, he started his own repair business.

As Uhrik built a reputation repairing guitars, people started bringing him their old instruments to sell, and retail ultimately became a large portion of his business. But the shop still has a busy workshop, where Minch is in charge — she became a luthier at Retrofret after buying her guitar. Everyone working at Retrofret seemed to be a musician of some kind — ranging from classical to jazz to revival rock.

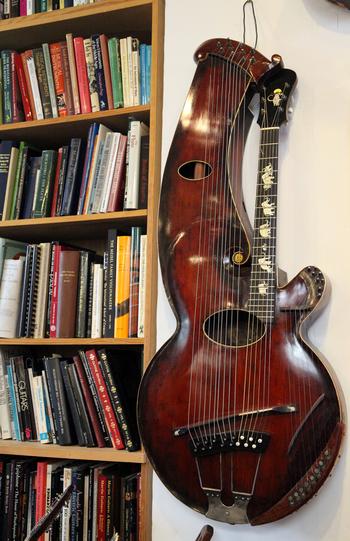

Customers include local and international musicians, who are searching for a specific sound, and guitar collectors. There are also institutions, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that want to display an instrument reflecting a very specific moment in time, like a Stroh violin (which has a giant horn jutting from its side — an early mechanical attempt at amplification). Some of the most unique instruments at Retrofret are essentially pieces of folk art, such as a 1905 dulcimer inside of which the maker glued bible verses.

With a few exceptions, the instruments Uhrik sells are pre-1975, and many date much earlier. Right now he thinks the oldest is a late 17th century French hurdy-gurdy (part keyboard and part violin, you rotate a crank and there's a wheel with rosin on it that rubs the strings).

In addition to nylon and gut stringed guitars, banjos, ukuleles and random musical oddities, Retrofret also sells electric guitars. Indeed, Uhrik has one of the earliest made — a 1935 Gibson that was part of a run of only 97. That piece costs a pretty penny, about $10,000. But Uhrik didn't seem to care if it ever sells; he's pretty attached to it.

Retrofret founder Steve Uhrik playing a Stroh violin. (Photo: Sarah Kate Kramer)

How did Retrofret start?

As a kid I always had an interest and real fascination with old mechanical things — phonographs and radios and that sort of thing. One of the real gifts for me is I ended up going to Brooklyn Tech and there I had access to machine shops and wood working shops for the first time, so as I wanted to play guitar I started building my own stuff and rebuilding broken guitars.

Were you in a band?

Yeah, several bands over the years, but I had more of a fascination with the technical end of things, the instruments, old instruments. I had a real interest in history, like civil war stuff as a kid. My mom had gotten me this double album, one album side was blue and the other was gray, and it was all civil war band music but played on original instruments and I think that really connected me to music and history.

Is there growing demand for vintage instruments?

Seems to be. It's an interesting market. We have some people who come in who want to buy an instrument that was made in the year they were born, if it was 1955, or 1965, that's sometimes a motivating factor for a collector. You have folks in my age category who owned certain instruments years ago when they weren't worth tens of thousands of dollars and want to recapture that now that they're more solvent, more stable, and then there's a whole group of people, especially in this neighborhood in Brooklyn, who are active musicians, who are recording and gigging, and they realize that old instruments just sound different, they smell different, they feel different and they enjoy bringing that to life.

What are some of the rare instruments you have?

The real stand-outs for me personally: In 1935 Gibson produced and shipped 97 electric guitars — among the first electric guitars — I have one of them here. For me, that's kind of rare and very cool. Back in the mid-40s, Hammond made a monophonic synthesizer, designed as an add-on for church music, kind of imitates a voice, maybe flesh out the choir a little bit, we have one of those. That was a hip find for me. There are things I'd never seen before that come in here. A Weymann super-jumbo guitar from about 1910 designed to flesh out a mandolin orchestra — a pre-electric instrument, so if you want to make it louder you have to make it bigger. An early 19th century key bugle — I've had brass experts in here who asked "how do you even hold it to hit the keys?" It's such a wacky and arcane design.

The guitar music in the outro was performed by Retrofret's George Aslaender.