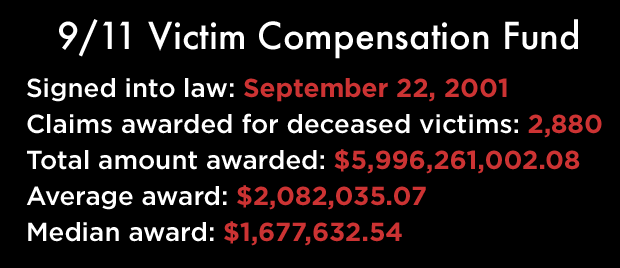

What if someone you cared for vanished forever, and you were handed a check for their expected lifetime earnings? In effect, that’s what happened to thousands of people whose loved ones died in the attacks of September 11, 2001. Never before in American history, and never since, has the government made payments to the families of the deceased, as it did through the 9/11 Victim Compensation Fund.

William F. Burke, Jr., was firefighter. Salman Hamdani, a lab technician and an aspiring doctor. Katherine Wolf, a pianist who worked as an executive assistant. All New Yorkers, they died on the same day, in the same place.

The government offered their survivors the same deal: collect a check for all the money your loved one might have made if they had lived, absolutely tax-free. And give up your right to bring a lawsuit.

Money, An Uncomfortable Gift

It still doesn’t sit well with Mike Burke, Billy Burke’s brother.

It still doesn’t sit well with Mike Burke, Billy Burke’s brother.

“It wasn’t like just a gift to the families, because everyone felt so horrified and sorry for what had happened,” Burke said. “It was basically an airline bailout bill. You know, protect them from suits that people feared would cripple, destroy the industry.”

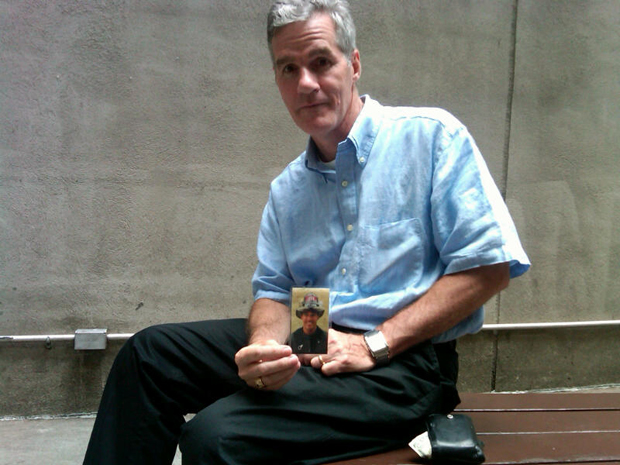

Burke is a soft-spoken man, with pale, almost watery eyes, very much like the portrait of his late brother that he keeps in his wallet (Photo right).

Almost from the moment he learned of his brother’s death, money came to Burke – not as a comfort, but as a burden. A few days after the attacks, Burke walked with his brother Jimmy through a family assistance center on Pier 94 on Manhattan’s West Side.

Everywhere the Burkes turned, someone wanted to honor Billy with a donation.

“There was organizations, Japanese organizations, Jewish organizations, organizations from everybody, just handing us checks. Five hundred, a $1,000,” Burke said. “It was a weird situation.”

After all, Billy was the hero, the one who tried to help a quadriplegic man escape from a burning building, and paid the price at age 46.

After Billy died, his life insurance went to some old girlfriends, to whom he’d stayed close. There was no wife, and no kids, so Billy’s five siblings -- all adults -- applied to the fund. Burke said there was little debate. Two of his brothers who were lawyers saw a lawsuit as a non-starter.

“The money was being distributed, and Billy would have wanted us to have it. Nobody went out and bought convertibles with it,” Burke said.

Burke used his portion to make a down payment on a home in Riverdale. The Burkes also set up a college scholarship fund in Billy’s name.

Money When They Needed It

Financial need, not moral uncertainty, determined Talat Hamdani’s attitude toward the fund. After her son Salman died at age 23, she stopped teaching school. Her husband, Selim, stopped going to his deli. They didn’t pay their mortgage.

“We were not bringing home any money at all,” Hamdani said. “And he was behind on his store rent also.”

Hamdani is a short, stout woman with hennaed hair, and plenty of charisma (Photo left). It’s hard to imagine that for months after the attack, she was in denial about her son’s death. Hamdani was completely unwilling to participate in the fund, until money worries forced the issue.

“We were financially definitely stressed out because we were not performing at all,” Hamdani said. “And when they said we have like three months left or something, my husband decided that we should apply, and I did not object.”

A family friend who was a lawyer, helped the Hamdanis with the application. But when the check came, they were disappointed. The award was for the minimum amount: $250,000.

A family friend who was a lawyer, helped the Hamdanis with the application. But when the check came, they were disappointed. The award was for the minimum amount: $250,000.

The Fund’s Special Master, Kenneth Feinberg, had calculated Salman Hamdani’s future earnings based on the fact that he was making $35,000 a year as an entry-level lab assistant.

But Salman Hamdani had planned to become a doctor, and Selim Hamdani prepared to contest the award, gathering papers that showed Salman was applying to medical colleges and had taken the MCAT exam.

Talat Hamdani showed up for the hearing with a letter for Feinberg, but then broke down, and asked her attorney to read it.

“And I remember I said, ‘The burden befalls a mother to prove the worth of her child,’” Hamdani said.

Feinberg listened, and responded by nearly doubling the award, to around $500,000.

The Hamdanis used the money to pay their debts. Talat moved with her two surviving sons to Long Island. She’s now raising money for a medical school scholarship fund in Salman’s name, and has become an activist on issues relating civil liberty and religious freedom.

She SAID the money from the Victim Compensation Fund was absolutely critical.

“I would give it up even today to get my son back. But it was a great help. Not even a small help. A great help,” she said.

Money to Look After

Katherine Wolf was 40 when she died. And from the start, her husband, Charles Wolf (Photo right), intended to be clear-eyed and methodical about the Victim Compensation Fund.

“First of all, I knew this wasn’t for the value of my wife's life. I knew that right up front, and I never looked at it that way,” said Wolf, who has curly gray hair, and wears glasses that magnify an already piercing gaze.

Wolf saw the program as a chance to have the same kind of justice you might get through a wrongful death lawsuit, but without going to court: compensation for shattered dreams.

“We saw ourselves with nice Manhattan apartment with view, with some space,” Wolf said. “We weren’t over top. But we wanted to be able to go out to dinner where we wanted to go out to dinner, whenever we wanted to.”

Today, Wolf does eat out a lot, mainly because he doesn’t like cooking for one. He still lives in the same rent-stabilized apartment he and Katherine shared. He works from home, doing direct sales with Amway.

Wolf won’t say how much money the fund awarded to him. Aside from buying a new car, he spent little on himself, and instead went shopping for a money manager.

“I went through and very carefully started interviewing different sorts of investment firms. I will not mention names. But I can tell you this: some of them came back with such god-awful proposals that it was insane,” he said.

Eventually, Wolf got a referral from a friend, and signed up with a little-known company which he trusted. “One of those firms that the big CEOs go to,” Wolf said.

There have been ups and downs. Wolf lost a lot of money on a Lehman Brothers bond in 2008. But, by and large, he said, the income from his investments has more than fulfilled the promise of the Victim Compensation Fund – to replace Katherine’s lost income.

And for Wolf, the money itself has become something to care for, even to nurture.

“My wife was gone -- she had been blown to smithereens. I was not going to blow this money,” Wolf said.

Charles Wolf, Talat Hamdani, and the Burke siblings are just three of the 2,880 claimants who lost a loved one, and were awarded almost six billion dollars in taxpayer money.

In the report he delivered to Congress, Special Master Kenneth Feinberg pronounced the Victim Compensation Fund a success. More than 98 percent of those eligible participated. Only a handful of families sued the airlines.

But Feinberg has also written that the formula was “defective.” He found valuing life to be an almost impossible task. “The family of the stockbroker and that of the dishwasher,” he wrote, “should receive the same check.” Or no check at all.

The Victim Compensation Fund, he says, is not a model that should be repeated.

Burke, Hamdani and Wolf all said the money raised questions for them, even though they accepted it.

“Loking at it from the Muslim perspective, there is a clause in Sharia law that if blood has been shed and victim's family are willing to be compensated, it is allowed,” Hamdani said. “And this is what that was. The only thing is, our government paid it out. Does that make the government accountable? That is another debate but it came in handy.”

And in the end, there is no way to put a price on life.