New York is a city of specialists from foodies to academics, laborers to shopkeepers. Every Wednesday, Niche Market takes a peek inside a different specialty store and showcases the city's purists who have made an art out of selling one commodity. Slideshow below.

Keur Djembe

568 Union St.

Brooklyn, NY 11215

Ibrahima Diokhane was having a terrible morning last Saturday. He was tired and, on the drive to his store, Keur Djembe ('House of Drums' in Wolof), he received a traffic violation.

He was in such a foul mood that he refused to come out of his basement workshop until a friend stomped loudly on the sidewalk grate above. Scowling, the 54-year-old immigrant from Senegal unlocked the door.

Surrounded by djembes — West African drums —of all sizes, Diokhane sat on a low stool and was soon persuaded to demonstrate the wide range of sounds his djembes are capable of making. Diokhane's hands rapidly fluttered over the instrument he had built himself, with materials imported from Senegal, and in short order his mouth flipped from an angry frown into a disarming smile. "It's therapy," Diokhane said after the last beat. He laughed. "I feel great, seriously, I forget about the little ticket for now."

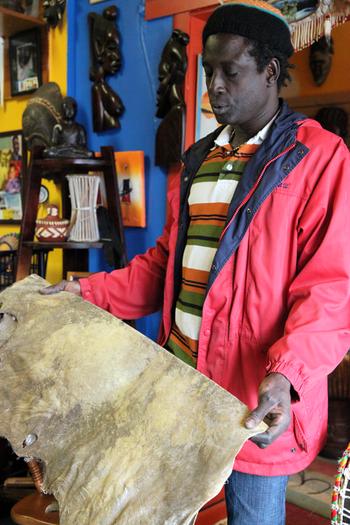

Diokhane was soon pulling various djembes off the shelves of Keur Djembe, which he opened in 1998.The tops ranged from velvety soft to rough, taut textures. When beginners come to the shop, he suggests a drum made with female goat skin, because it's thinner, and he'll send them home with a pat of shea butter for moisturizing the drum skin.

In his workshop downstairs, Diokhane keeps swatches of skins that he imports from Senegal. He cures and bleaches the skin before stretching it onto the mahogany wood shells, then tunes the drum with nylon ropes — the only part of the drum he purchases in the U.S. The large djembes costs $350, and the baby sized ones are $25.

It was never Diokhane's plan to become a drum retailer in the U.S. After immigrating in 1980, he worked many odd jobs — a baker, a taxi driver, a street vendor — and oddly enough it was while selling clothes on the street that he built his reputation as a drum-maker. He took a drum to work and played to pass the time vending, and there he got noticed.

"People start coming to my apartment asking for the guy who makes the drums. I'm like, 'it's me,' and drums start popping up my house like fruit!" he recalled.

His landlord offered him the retail space he still occupies, below his apartment. According to him, no one has ever complained about the noise coming from the shop. Diokhane, now a father of seven, chalks his trajectory to fate. He claims to be completely self-taught, and to have sold his first drum at the age of 12 after dropping out of school — constructed from a coconut shell and shark skin he found on the beach. "The drum making is just something God put in my hand, it's a gift of God," he said.

In New York these days, most of Diokhane's business is repairing drums and giving lessons. He sells drums every so often, but many of his days at the shop are spent with window shoppers like Salim Rahman, who stopped for a break while distributing brochures for a Chinese food restaurant. Rahman learned to play drums in Bangladesh, and his eyes hungrily digested the wealth of instruments crammed into Keur Djembe's small space. He knelt and beat on two small djembes, playing them like he would a tabla.

Outside of djembes, Diokhane has a few Middle-Eastern, Japanese and South American drums for sale. But djembes are the most popular because of the amount of tones it produces, and its volume, Diokhane believes. "This is an instrument, let me tell you, even if a little baby, pass through right now here, they will make mom stop, that's the djembe."

Where did you learn how to make drums?

2:25 Well drum making it comes to me, it's just, I'm born with it. Because when I was a little boy you can say by four or three years I started stretching skin. In cans, I'd go find cans of tomatoes, or cans of fruit, I just picked it up and skinned it--put the skin on there and stretched it. It was just something, I could just stretch any skin, put it somewhere and start banging on it, and start hearing the music. And from there, I just making drums. After I drop out of school, 12 years old, because my mom could not afford to do nothing for us, something told me to go to the beach and when I'm at the beach I'm swimming, playing, whatever, helping people, after they give me the fish, I always get some shark fish, left over, because they don't eat that fish, so I take the shark fish, and usually you have a coconut tree there by the beach. I used to take the (coconut) shells, take the shark skin put them on the shell and make drum with it. And I used to sell them! Little drums I used to make them, the tourists started seeing them, I used to have a little stick and started playing like this. (Demonstrates) And they say 'wow, you make this?" I said 'yeah,' and I started selling them on the beach. They used to give me anything, a quarter, some people maybe a dollar. I was a little boy and I remember when I go home my mom is so happy because I started to have a little job making drums.

Interview with Ibrahima Diokhane

Where did you learn how to make drums?

Drum making, it comes to me, it's just, I'm born with it. Because when I was a little boy, you can say by four or three years, I started stretching skin in cans. I'd go find cans of tomatoes, or cans of fruit, I just picked it up and skinned it — put the skin on there and stretched it. I could just stretch any skin, put it somewhere and start banging on it, and start hearing the music. And from there, I just start making drums. After I drop out of school, 12 years old, because my mom could not afford to do nothing for us, something told me to go to the beach and when I'm at the beach I'm swimming, playing, whatever, helping people, I always get some shark fish, left over, because they don't eat that fish. So I take the shark fish, and usually you have a coconut tree there by the beach. I used to take the [coconut] shells, take the shark skin put them on the shell and make a drum with it. And I used to sell them! Little drums, the tourists started seeing them, I used to have a little stick and started playing. And they say 'wow, you make this?" I said 'yeah,' and I started selling them on the beach. They used to give me anything, a quarter, some people maybe a dollar. I was a little boy and I remember when I go home my mom is so happy because I started to have a little job making drums.

What's special about African drums?

They're the best drums. African drumming is me, Ibrahima. It's therapy. What I tell people is, 'your hand is moving but your brain is playing.' It's any music — if your brain doesn't sing what you're playing, your hand will not do it. My therapy part is first to teach people balance, the left side of your brain to the right side of your brain, and two, it helps people with relaxation, because I teach people how to relax, sit right, and make them forget their problems sometimes, when they come out of the office or home, want to be somewhere else.

Who are your customers?

My customers are lovely. All colors: white, black, Japanese, Jewish, Indians, anybody has a drum, their drum comes here I fix them, I'll fix any drum. I got a lot of kids coming from Israel, they buy my djembes, bring it to Israel. I got a lot of guys coming from Japan, even when their drum breaks in Japan they bring it here, I fix them. I got a lot of customers in the Haitian community, I have the West Indian community, in Brooklyn, all the white boys playing drums, in schools and hippies, they're all here. As long as you love the music, you're welcome to come.