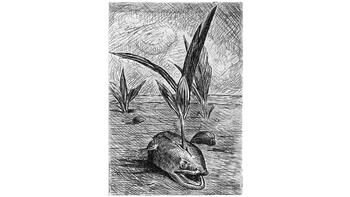

Eels should be the token food for Thanksgiving, argues author and artist James Prosek. Turkey may be the food most associated with the holiday now, but eels were a crucial component of the pilgrims' survival during their first brutal year in the New World.

The pilgrims landed at Plymouth in the fall of 1620, but by March of the following year, half of their group had perished from starvation and disease. After the Native Americans decided to declare peace with the pilgrims, Squanto went fishing and brought back as many eels as he could carry.

“Really it’s the eels that kept the pilgrims from starving,” said Prosek. “And it was for the Indians, as well as for early colonists, and important source of nutrition.”

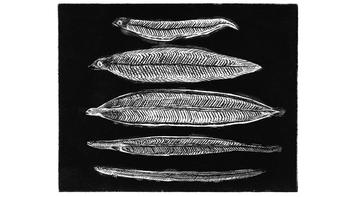

One of the best times to catch eels is in the early fall, when American freshwater eels begin their migration to spawn in the Sargasso Sea, about 1,500 miles east of Bermuda. The eels that make the trip have usually spent between 10 and 30 years living in fresh water.

“Almost nothing is known about the life history of the eel beyond that because we’ve never witnessed adult eels spawning in the Sargasso Sea,” Prosek said. “But we know they spawn out there because we’ve netted the babies drifting on the surface of the ocean.”

This year’s eel run was impacted by the tropical storms that swept through the East Coast recently. The migration normally corresponds with the hurricane season because elevated water levels make it easier for eels to get out to sea, said Prosek, whose book Eels: An Exploration, from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World’s Most Mysterious Fish is out in paperback on Tuesday. The stages of the moon and tide levels also play a part in triggering the mass move.

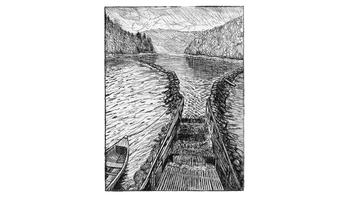

In Hancock, New York, along the Eastern branch of the Delaware River, Ray Turner has been operating an eel weir, or fishing trap, for about 25 years. (He is pictured below, standing in the weir.) He says this year’s rains brought unprecedented high water.

“We’ve had probably 10 to 15 feet of water over the top of the fish trap at least 16 times this year,” said Turner. “I haven’t even an idea what’s actually happened as far as the eel migration is concerned.”

The eel weir is composed of two long stone walls that form a "V." At the vortex on the downstream side is a multi-tiered wooden trap. Prosek, who has helped Turner rebuild the stone walls in the spring, explained that this year’s flooding has caused the eels to slide right over the weir. As a result, Turner said that his store, Delaware Delicacies Smoke House, will focus on selling other smoked goods, like trout and cheese, this year.

Prosek notes that eel populations have declined in general due to factors like changing water temperatures and the construction of dams. He’s heard reports of migrating eels getting caught in the turbines of hydroelectric dams, causing brownouts.

“Historically, before the major decline in eel populations, hundreds of millions of eels would be running down East Coast rivers to the Atlantic Ocean,” said Prosek. “It’s just amazing to see — just like ropes of eels slithering down river. And sometimes even coming out of the river to get around obstacles. They can cross over land on wet nights. As long as their skin is moist, they can breathe cutaneously through their skin.”

Strange attributes like that have made the slimy, slithery fish the focus of myths and folklore around the world.

Preparing eel requires caution, though.

“Eel is always served cooked because the blood has a neurotoxin,” Prosek said. “Cooking the eel neutralizes the neurotoxin.”

He added that ambitious fisherman should be careful not to get the blood into eyes or open wounds.

For those who are less motivated to prepare the fish themselves, below are a few recipes for using smoked eel. Also, check out a slideshow of Prosek’s etchings for his book, as well as his photos of Turner’s eel weir.