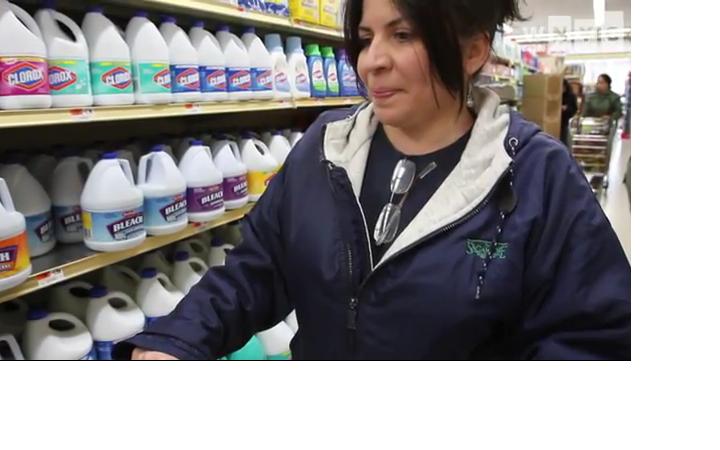

In our new series On the Brink: The New Face of Poverty, meet Yolanda Cotto, an unemployed mother of three who is facing homelessness as she, like many Americans, grapples with supporting her family and tries to get back on her feet.

With tears rolling down her cheeks, Yolanda Cotto, 53, recently sat in the front row of a packed courtroom in the Bronx Housing Court writing two money orders and a check totaling $2,000 that would enable her to keep the Bronx co-op she has called home for 30 years.

Only two years ago the fiery mother of three, with a Master’s Degree in psychology and a model resume, could never imagine being in this situation: unemployed, on public assistance and defaulting on maintenance fees for the two bedroom co-op on Seward Avenue she bought in 1982, paying only $1,800.

“You work all your life,” Cotto said, her voice cracking. “And then you wind up like this. I just don’t understand. I can’t get it. I can’t get it why I can’t get a job.”

Outside the Bronx Housing Court, the Dow was inching upward, and the economy was showing strong signs of recovery. But for Cotto and many other New Yorkers escape out of poverty remains a daily struggle.

The Bronx native, who has worked in managerial positions for various non-profits and the city for 30 years, is one of more than 120,000 New Yorkers who lost their jobs from March 2008 to November 2009. Today, Cotto remains one of over 361,000 unemployed New Yorkers. Based on her disposable income, she is among the 20.1 percent living below the poverty line.

Falling Out of the Middle Class

Cotto’s descent from the middle class began in 2009, when she was laid off from a position with the city’s Department of Education ensuring children with special needs were matched with proper resources. She earned $79,000 annually.

“It was April 17, and I knew something was not right cause we usually have a cabinet meeting,” she said. “I was told I didn’t have to attend that meeting.”

Cotto was laid off due to budget cuts. She immediately started receiving unemployment benefits, $405 a week and $376 in food stamps. That largely helped cover her monthly maintenance fee of $1029 for the co-op, groceries, as well as other expenses, such as transportation, which can add up to $120. But soon she had to dip into other resources.

“I took everything out of my pension, I absorbed all resources,” Cotto said. “I have nothing.”

She took $15,000 out of her retirement fund, the maximum she could pull out before turning 59. And in December, the unemployment benefits were replaced with public assistance, a much smaller sum of $283 every two weeks.

The hardest days are those when she’s reminded of the things she could once easily provide but no longer can: a movie ticket for her 12-year-old son; a gift to her 37-year-old daughter’s newborn girl; help with college expenses for her 22-year-old daughter.

Cotto said she is currently unable to make a profit by selling shares in her co-op building due to terms of her contract.

At 53, Cotto is too young to retire and too old to climb the ladder from the bottom. She has had trouble finding jobs suited to her skills and experience. In the past two years, Cotto applied for around 20 positions, from telemarketing to cashier to case worker. She has been regularly checking job postings online as well as dropping off her resume at various day care centers in the Bronx.

Marisa Di Natale, director of policy research for Moody’s Analytics, said people like Cotto are in an especially tough situation.

“The people that have been out of work for a very long time tend to be more disproportionately older,” Di Natale said. “That’s sort of double stigma against them. Employers may not want to hire people that have been out of work for a long time, but they also may prefer to hire someone that’s right out of college and is cheaper.”

Cotto received her Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology from Fordham University in 1983 and began working in East Harlem as an intake officer for The New York Bilingual Institute, which provided vocational training and employment assistance to its clients or the area’s residents.

She earned a Master's degree in psychology from the College of New Rochelle in 1993.

On a recent sunny afternoon, she stood on Third Avenue in the South Bronx. It’s a block with housing projects on one side and a building with three public schools on the other side. Cotto worked here as the director of the Beacon Community Center until 2003.

To a passer-by it might seem like any other building in the neighborhood, but to Cotto it holds what she said were the best memories of her life.

“This was one of my biggest accomplishments,” she said. “I was here for 13 years. It was a wonderful place to be. Wonderful.”

The school-based centers were first opened in neighborhoods with high crime rates in the 1990s. Eighty still exist today in the city, providing tutoring and sports classes for kids and parenting skills for Moms and Dads outside school hours.

“I grew up in this neighborhood,” Cotto said, referring to her childhood home only a short distance away. “I was a little girl. I went to school around here. So, for me giving back was one of the best things that could happen to me in my life.”

“I don’t leave this house. I don’t go anywhere,” Cotto said. “My highlight is going to the supermarket. And that’s my daily activity every other day. I’m basically here and sometimes I just pace the house.”

Mimi Abramowitz, professor of social policy at Hunter College, said inability to find a new job can have a detrimental impact on people’s psyche.

“We’re a very work oriented culture,” Abramowitz said. “Most of us get our identity from work. People are devalued if they don’t have that identity.”

Uncertainty Prevails

Before her court appearance in February, Cotto despaired over how to come up with the money she owed her co-op. She feared the judge might evict her if she was unable to prove she could cover her $6,000 debt, which she accrued after failing to pay monthly maintenance fees of $1,029 for several months, beginning in 2009.

“I have no idea how I’ll get the money,” Cotto said at the time. “I might be homeless.”

The day before her court appearance, Cotto received two money orders from her sisters and a check from her ex-husband.

Her two sisters and friends pulled together once again and in the second part of February came up with the rest of the money she owed in maintenance fees for her co-op.

Still, the relief is only temporary: This month, Cotto needs to come up with the regular maintenance fee of $1029.

The one thing that keeps Cotto busy is the daily struggle to survive.

“Now I still have to look at how I am going survive the month of March,” she said.

Video and photos by Jennifer Hsu/WNYC