1962 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award

"Race Relations in America," is the self-proclaimed theme of the 1962 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award winners. The prize, whose mission is to recognize works of social justice, goes to three books, Black Like Me by John Howard Griffin, The Forbidden Man, by Gina Allen, and Anti-Slavery: The Crusade for Freedom in America by Dwight Lowell Dumond.

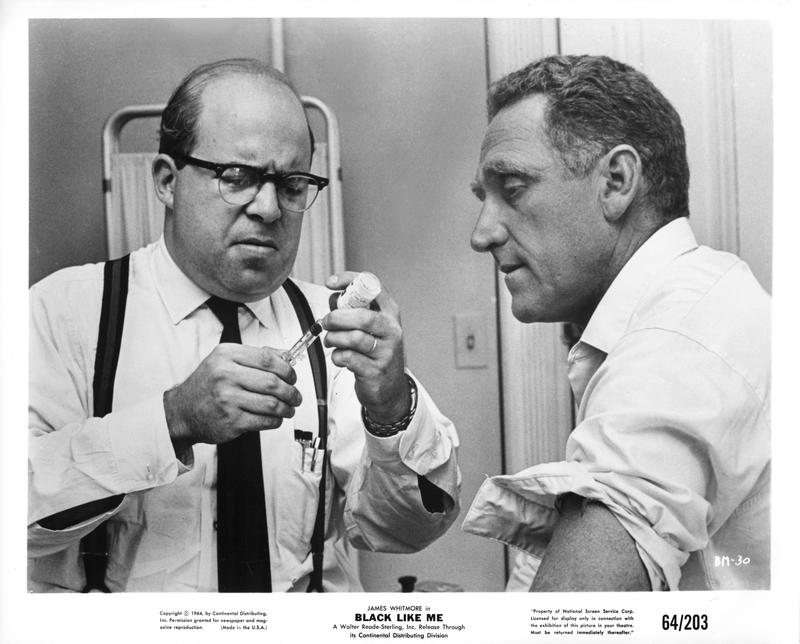

As the books represent three different genres (memoir, novel, and work of history) the host has a difficult time getting the conversation going. Gina Allen speaks of her novel being about how "barriers lead to a lack of understanding, and in the lack of understanding you have the germs of hate." Dumond, a professor of history, starts out with a rather dry exposition of the anti-slavery movement, before characterizing the institution itself as "a form of social insanity." Griffin, the most well-known of the three, whose "stunt" of having a dermatologist to darken his skin so he could travel throughout the South as a black man, is a more passionate, voluble witness.

Griffin describes the hardship of simply having nowhere to eat, to get a glass of water, or answer any other bodily needs, of the dread he felt leaving his room, of having to think very carefully before taking any action, with the threat of violent consequences lurking behind the most innocent impulse. Of blacks and whites in America he proclaims, "We know nothing whatsoever about each other!" Allen refers to an apparently common phrase of the time, the "hate stare" blacks encounter from racist whites. She also points out how racism destroys white families and as well as black. Dumond speaks of the brain drain the South has suffered for many years as any white with the conscience or intelligence to question the system of apartheid is forced to leave.

There is still, in 1962, a widely-held belief that the Negro is genetically inferior. Much time is devoted to debunking these and other myths. Griffin speaks of how, when hitch-hiking, he was invariably asked about the black man's enormous sexual appetite. The conversation, with its conspicuous lack of black representation (this in a year that saw the publication of James Baldwin's Another Country) is a well-intentioned but disturbing snapshot of the white literary community trying to formulate a response without engaging the very people whose predicament is being discussed.

Gina Allen (b. 1918) was the author of many books and articles. The Forbidden Man was her first novel. Kirkus Review called it:

An earnest, angry and often moving novel about integration in the Spanish-White-Negro-town in the southwest…There is a touch too much melodrama and too many side plots in this story, but the author has right, knowledge and indignation on her side, and the central scenes, of a Negro teacher at bay among the disturbed from an even more disjointed background, are frequently stirring.

Dwight Lowell Dumond (1895-1976) taught for many years at the University of Michigan. Anti-Slavery was his magnum opus. As the university's memorial tribute notes:

Dumond's antislavery publications were cited in oral argument by counsel for the plaintiffs in the school segregation cases to supplement their written briefs.

John Howard Griffin (1920-1980) was a novelist, journalist, and social activist. It is hard to overstate the impact Black Like Me had in a time when the inequities of the South were not widely reported and, even when done so, not widely believed. Something about the bizarreness of Griffin's self-willed transformation, perhaps the very urgency such a drastic act implied, made his revelations more than mere muckraking. Jonathan Yardley, book critic for the Washington Post, recalled its effect when revisiting the book fifty years later.

I was 21 years old, newly graduated from Chapel Hill. I had written sympathetically about the emerging black protests for the student newspaper, but I was deeply ignorant about the truths of black life in America. That it took a white man to begin my awakening is, in hindsight, distressing, but Griffin's story managed to put me in a black man's shoes as nothing else had. …"Black Like Me" had a transforming effect on me, as apparently it did on innumerable others. That it has remained in print for more than four decades is testimony to its continuing influence, in great measure because it is taught in high schools and colleges.

Fittingly, the last word is given to Griffin, who states, "We don’t have a race problem in the United States, we've got a problem of racism."

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

WNYC archives id: 150268

Municipal archives id: LT9452