Less wealthy, more racially diverse: That's the donor profile for elections in New York City, where a system of matching small campaign donations with public funds allows minorities and lower-income individuals greater influence than in state elections without a similar system, according to a new study.

Published Monday, the report from the Brennan Center for Justice and the Campaign Finance Institute (CFI), entitled “Donor Diversity Through Public Matching Funds”, compares the 2009 City Council elections with the 2010 State Assembly elections.

The city's system matches campaign donations at a 6-to-1 ratio, up to the first $175 a person contributes to a participating candidate. No such program exists at the state level, although State Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, a Democrat, introduced a bill to establish one in April.

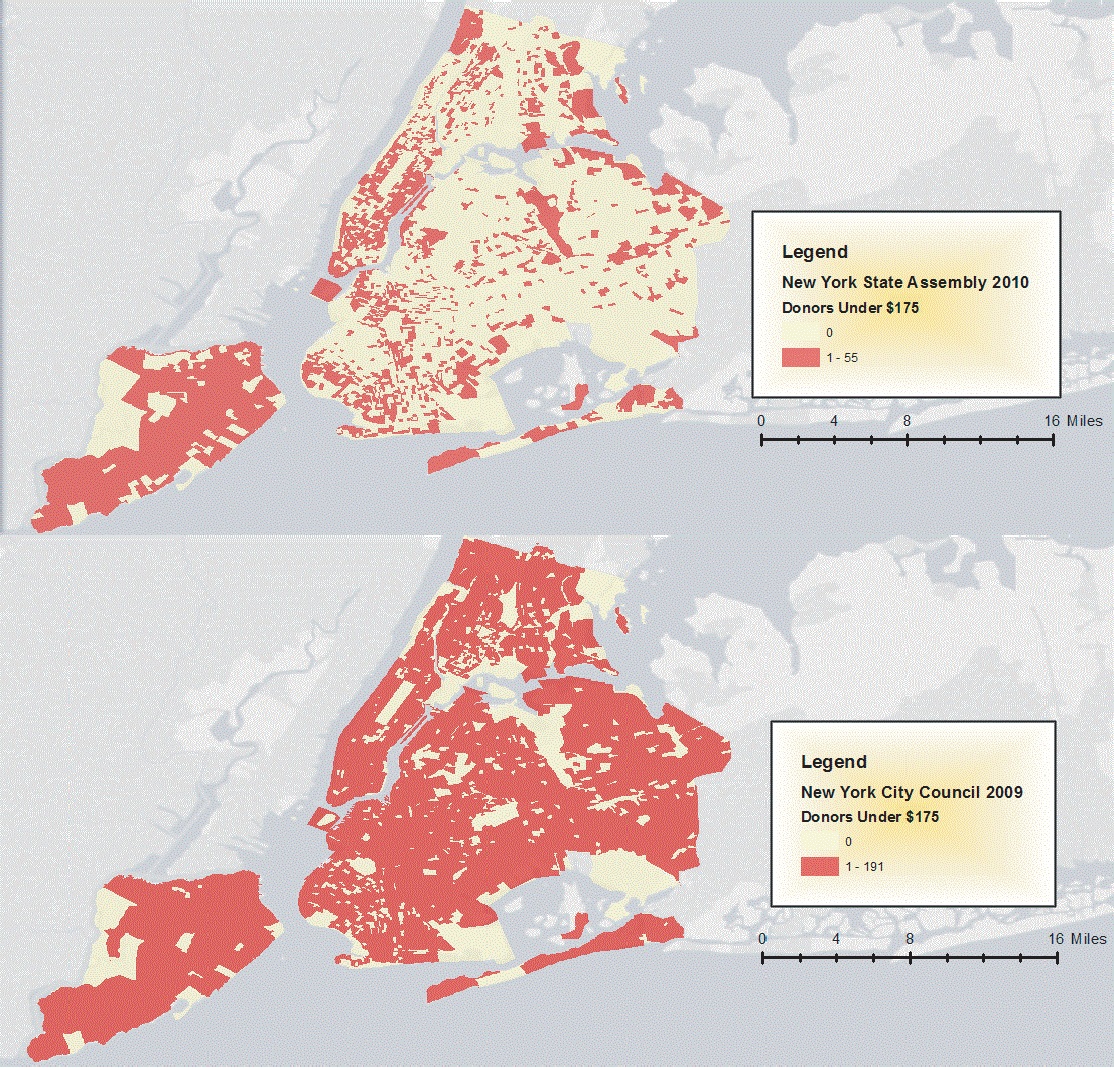

In their analysis, CFI and the Brennan Center found that 90 percent of census block groups in the city were home to a small donor (giving $175 or less) in the 2009 City Council elections, whereas small donors came from only 30 percent of census block groups in State Assembly elections the following year.

NYC census block groups with at least one small donor, 2010 State Assembly v. 2009 City Council

Source: “Donor Diversity Through Public Matching Funds” (CFI / Brennan Center)

"Almost everyone in the city, from the richest of neighborhoods to the poorest, lived within a city block or so of someone who contributed to the 2009 City Council elections," the report says. "The donors looked and lived like the neighbors in everyone's neighborhoods, because they came from literally all over the city. This was not even close to being true for the donors in the 2010 New York State Assembly elections."

The poor and predominately black neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn was home to 24 times more small donors for City Council elections than State Assembly elections. There were 23 times more small donors from Chinatown, and 12 times more in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx, all neighborhoods with large minority populations.

"Matching funds give city candidates an incentive to look actively for small contributions," the study reads. "As a result, the donors who gave to City Council candidates in 2009 came from a broader swath of less wealthy and more racially diverse neighborhoods than did the donors to candidates for the State Assembly in 2010."

City politicians confirmed the study's findings with anecdotal evidence.

"I'm in a community, the south Bronx, where there aren't a lot of people with great personal wealth," State Senator and former City Council member Jose Serrano said in an interview with the Brennan Center. "This is a working class community, and my neighbors can't drop $1,000. But being able to raise $10, and with the match being so significant, really made these small donors very important."

Serrano says that once he ran for State Senate, where there are no matching funds, his campaign had to lean much more heavily on well-heeled donors and people outside of his district.

Another fan of the system? Governor Andrew Cuomo, who in his 2012 State of the Union speech proposed adopting a state-level matching funds program to be modeled after the city's.

Do you know 50 people with $2,000?

From a potential candidate's perspective, the main argument for matching funds is that you don't need to have a lot of rich friends in order to run for public office.

From a voter's perspective, the main argument for matching funds is that they incentivize candidates to talk to more of their constituents; spend more time on the ground in their districts; and generally owe less to specific individuals with deep pockets than to the community as a whole.

"Our representatives spend most of their time now thinking about a very small set of people's problems and how to solve them because of the way our campaigns are funded," said Zephyr Teachout, an election law professor at Fordham University.

In 2005 Teachout explored running for Congress in Vermont, where Bernie Sanders was vacating his seat to run for Senate. The state has no system of matching contributions.

Teachout was told that she'd need to raise $100,000 before the press would take her seriously. "My first job then, according to all the professionals I talked to, was make a list of everybody I know who could give $2,000, and try to get to 50."

"It's an interesting project. Everyone should try it."

After all, what sort of people have $2,000 to contribute to a congressional campaign?

"Imagine being a public school teacher in Bushwick who may have a lot of amazing ideas," Teachout said. "Do you think they have 50 friends with $2,000 to spare?"

Teachout's experience was that being a "viable" candidate had less to do with ideas than money; matching funds are supposed to shift the balance back in the other direction.

"I would spend my day thinking about gun control because gun control was an issue that was really important to my wealthy New York City friends," Teachout said. "It's not a big deal in Vermont. I felt myself trying to solve the questions that were not the questions of my would-be constituents."

The price tag for taxpayers

Conscience do cost, though.

Further analysis from the Campaign Finance Institute showed that matching funds costed New York City $25 million in the 2009 elections. Introducing a similar system at the state level and assuming an uptick in small donations as a result, CFI estimates that it would cost about $79 million.

For that reason, Mike Long, chairman of the New York State Conservative Party, is not a fan.

"I don't believe taxpayers should have to fund individuals' campaigns that they don't agree with or don't support," Long said. "New York State has enough problems as it is."

That it would placing undue burden on the taxpayer is Long's primary objection to matching funds, but Long also cites possible corruption as a reason to avoid implementing the system elsewhere.

"Matching funds have turned into a business where people who run for office wind up hiring their own family members, wind up buying all sorts of computers and equipment, et cetera, then the campaign is over, they lose, and they're the beneficiary of all the office equipment. And the taxpayers paid for it."

Long also identified New York City Comptroller John C. Liu as an example of how the system can be abused. Liu, who's been collecting donations for a potential 2013 mayoral run, has been dogged by allegations that his campaign funneled money from wealthy donors, way over individual contribution limits, through "straw donors" who would contribute smaller amounts. This would help disguise any wrongdoing and allow the campaign to take advantage of matching funds.

But Liu's campaign came under fire before the matching funds program kicked in, which won't be until 2013. For all the small donor contributions Liu received, no public money has been given to his campaign — perhaps a sign that the system works.

That's not enough of an assurance for Mike Long. "I'm very pleased that they caught him, but I'm sure it's been done by many City Council candidates," he said.

Despite the approval of Governor Cuomo and the support of Assembly Speaker Silver, a bill to implement matching funds for the state appears to be DOA in Albany. Republican Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos has declared opposition to the legislation, and Mike Long has his back.