Art in Public: Stuart Davis on Abstract Art and the WPA, 1939

This live dedication of four Works Progress Administration (WPA) murals in WNYC’s Studio B is most notable for the comments of abstract artist Stuart Davis, the only one of the murals’ creators in attendance.

Unlike the other two speakers, the architect Eugene Schoen, and New York State Director of the Federal Art Project, Audrey McMahon, Davis takes the opportunity to speak bluntly about art and politics. His concrete points, cranky tone, and flat American accent stand in stark contrast to the other speakers’ empty officialese and “cultivated,” anglicized vowels. The brief silence following his comments, along with the gradual smattering of sparse applause they receive, is also nothing like the heartier responses elicited by all other segments of the program.

In a ceremony clearly designed to be light and “festive,” according to the announcer, Davis squarely addresses the elephant in the room: the fact that pending legislation to extend and expand federal arts funding is under heated attack at the moment, sentiments he expressed, more formally and less unexpectedly, a year and a half earlier, discussing the legislation on WNYC’s weekly Forum of the Air broadcast. At both events, Davis also finds time to lambast various members and practices of the art establishment, one of many social and political debates occasioned and encouraged by the WPA’s establishment in 1933. Even the agency’s name was a lightning rod, and was changed a month after this broadcast, from the Works Progress Administration to the Work Projects Administration.

Sandwiched between three contemporary classical music selections performed by the WNYC Concert Orchestra, the speakers all take the opportunity to praise the WPA, its ideals and accomplishments. Only Davis mentions the embattled legislation, also taking the opportunity to decry the pernicious role of private patronage, and the suppression of abstract art by “certain reactionary museum-critic-dealer combines in the United States,” which he compares to Hitler’s. Considering endangered arts funding, he also finds “grim humor” in Congress’s recent appropriation of $2,500 for a White House portrait of “ex-President Hoover.”

Following him, McMahon forges on nonetheless in bland institutional style, certain, she says, that all WPA artists, as well as “hundreds of our sponsors and the public of this great station,…are heartened as we are by the enthusiasm which has been expressed here.” As for the role of abstract art, its use here, she says, “demonstrates the practical approach taken by the Federal Arts Program to all types of art. We believe that all directions in painting have value, but only when used in relation to the architecture and purpose of the room or the building in which they are planned,” a regimented view also expressed by Schain. The next day's New York Times coverage [1] quoted more of the project’s PR, which states that abstract works “are particularly suited for use in a modern broadcasting studio, where everything must contribute to quiet and the uninterrupted function of the broadcast… [because such a style] does not serve as a distraction, but…actually exercises a soothing influence on the observer, through the proper use of form and color.”

Such proscriptions reflect the flux and struggle around the issue of abstract art during the previous two decades, a state of affairs reflected in the lives of Davis and two of the other muralists: Byron Browne and Louis Schanker. These men, half a generation younger than Davis, one a champion of the purely abstract, the other working somewhat representationally here, were engaged in long-term, active protests of major museums for their neglect of abstract work, both before and after this unveiling. Schanker’s first showing, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1935, took place within a year of his own participation in one such protest against the same institution. Browne, after adopting abstraction at age 20, claims to have later destroyed all his earlier work. When some of it won a prestigious prize a year later upon his graduation from New York’s National Academy of Design, he famously rejected it, in protest of the school’s refusal to embrace modernism. A few years after this broadcast, he picketed the Museum of Modern Art.

All three men grew up in Northeastern cities, studying art at an early age. All completed several murals during their lifetimes, taught at various New York art schools, and were active in the WPA early on. Browne was a member of the first artists’ union and his participation in the American Avant-Garde movement helped make New York City a world art center. Schanker was a major printmaker in the 1930s and one of the earliest woodcut artists to make abstractions; he was also a sculptor. The fourth and oldest artist, John von Wicht, was born in Germany two decades before Browne, the youngest. Von Wicht’s work encompassed mosaic, illustration, and book and architectural design as well. His turn-of-the-century, Old World training was both more classical and extensive than the other men’s, and he had completed his first abstract works only two years earlier, in middle age. Yet Von Wicht’s mural is a pure geometrical abstraction, an outgrowth of the work of Wassily Kandinsky, according to New York Times art critic Edward Alden Jewell, who links Browne’s mural, in contrast, to the style of Piet Mondrian. Of all the works, Schanker’s is the most representational -- with easily discernible musical images -- and Jewell praises this one most.

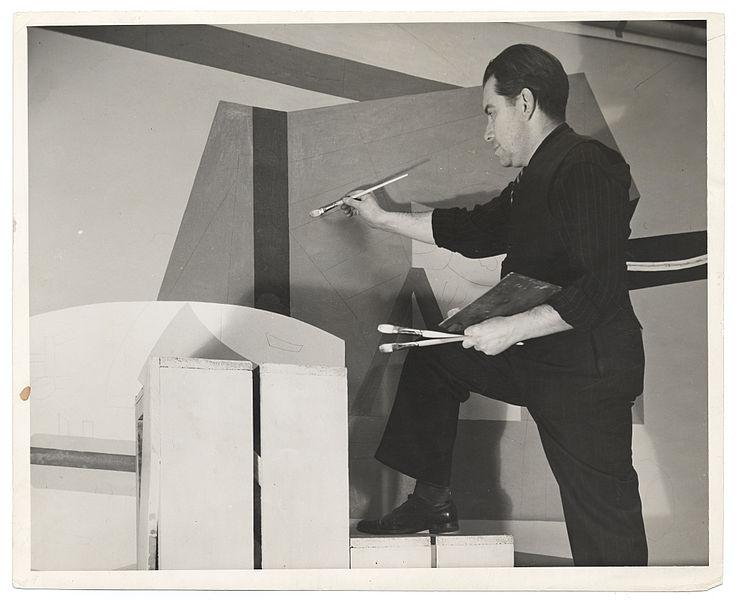

This may be partially because the PR for the series, as Jewell notes, stressed music as its unifying theme, using analogies that seemed to the reviewer “sometimes forced or lugged in.” One he takes issue with is Davis’s characterization of his own approach as “symphonic.” Considering his mural in this light, Jewell describes its development of a theme as “ragged, episodic, and incoherent.” He does, however, own that, among the other abstract pieces, Davis’s is the most original. The work is also alone in its lack of clearly man-made shapes and a sense of relative balance. It seems, instead, a unique collision of the organic and the inorganic, the half-known and the unknown, its startling composition suggesting less a unified plane than the schemata of an urgent object (or three) engaged in some mysterious process. Davis’s notes for the piece describe his intention to create "a series of formal relations which are identified with musical instruments, radio antenna, ether waves, operator's panel, electrical symbols, etc.” Davis also believed that radio transmissions manifested “the essence of abstraction.”

Davis, a painter, printmaker, cartoonist, and graphic designer, was born to artists in Philadelphia in 1892. He was one of the youngest painters to exhibit in New York’s controversial 1913 Armory Show and went on to become a singularly influential American modernist painter, tireless art advocate and popular educator. Exploring urban realism, cubism, collage, and decorative styles, as well as, most notably, abstraction, though he regretted that his work had been "typecast" by the term, claiming that every piece had its source in observed reality: "I paint what I see in America; in other words, I paint the American Scene." In a 1943 Art News interview he listed items "which have made me want to paint…: the brilliant colors on gasoline stations; chain-store fronts, and taxi-cabs; …synthetic chemistry;…Rimbaud; fast travel…electric signs;…5- & 10-cent store kitchen utensils; movies and radio…." Much of what he saw, and painted, also included commercial posters, packaging, and typography, inspiring later critics to cite him as an early Pop-art pioneer. His love of jazz also contributed to the rhythms and compositions of his work, including WNYC’s mural. Abstract art, Davis comments here, “has already modified the shape and color of most of the products of industry,” and has made an “important contribution…to our modern conception of the real world.”

For the mural, Davis was paid hourly for about two months of work, for a total of $335, materials included. The murals were executed in WNYC’s Studio B during what the Assistant Program Director, Seymour N. Siegel, recalled as a “hot, sticky summer.” Their completion marked the “finishing touches” of several years of revamping and expanding of the station, which had begun limited broadcasting in 1924. It’s noted here that the installation and construction of the new studios and transmitter in the late 1930s were also completed with WPA labor. It’s not noted that the WPA had also paid for the 35-piece orchestra playing that night, as well as at least a dozen other WNYC music ensembles. In 1936 the WPA underwrote half of WNYC's broadcast hours, and its support was credited by Siegel with changing Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s mind about closing the station two years before. Since that time, WNYC had flourished and the relationship had changed, so in closing, McMahon thanks the Mayor for aiding the station’s growth from “a one-room studio to the outstanding city-owned radio station in the United States.”

A few years later, Davis wrote:

An artist who has traveled on a steam train, driven an automobile, or flown in an airplane doesn't feel the same way about form and space as one who has not. An artist who has used telegraph, telephone, and radio doesn't feel the same way about light and color as one who has not. An artist who has lived in a democratic society has a different view of what a human being really is than one who has not. These new experiences, emotions, and ideas are reflected in modern art, but not as a copy of them.

In 1947, Life magazine, previously among abstract art’s detractors, published "Why Artists Are Going Abstract: The Case of Stuart Davis," a seven-page feature, in which Davis patiently explains, "the aesthetic is a well-known formula among American artists…so well known that it is continually used in popular media such as posters and smart advertising layouts." By 1954, Time magazine was calling him "American as bourbon on the rocks," an artist whose works "echo the clash and clatter of 20th-century American life." Yet two years later, Davis was still being called on to defend the realism of abstraction. Appearing on the television show "Night Beat," he said, “realism doesn't include merely what one immediately sees with the eye at a given moment -- one also relates it to past experience... one relates it to feelings, ideas. And what is real about that experience is the totality of the awareness of it. So, I call it 'realism.' But, by 'realism' I don't mean it's a realism in any photographic sense -- certainly not."

Davis died in New York in 1964, preceded by Browne in 1961, and followed by von Wicht in 1970, and Schanker in 1981. Davis remains the best known.

A year after his death, Davis’s mural, 7-feet-2-inches by 11 feet, now valued at "$60,000 to $100,000," according to The New York Times, went on three-year loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it remains to this day. The Times’s coverage reports that the removal and maneuvering of the gigantic three-panel work through several inadequate doorways produced “some tense moments.” By then, the work had been out of view for some time, obscured by a curtain in what had become the newly christened television studios of WNYC’s Channel 31. Schanker’s mural is still in the Municipal Building, hanging in a hallway on the 25th floor. Von Wicht’s is displayed on the third floor of the Brooklyn Public Library Grand Army Plaza Branch. Browne’s was damaged and is in pieces in the basement of City Hall under the auspices of the New York City Design Commission.

[1] Abstraction and Music, 8/6/39, by Edward Alden Jewell

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

Note: Some poor audio quality due to condition of transcription disc.