The Activist Tom Mooney, on Death Row, Is Pardoned

This dramatic live broadcast from 1939 is a seminal moment in American jurisprudence and political history: the pardon of Tom Mooney, a tireless labor activist wrongly condemned to death in 1917 for a fatal bombing, after he served 22 years in prison.

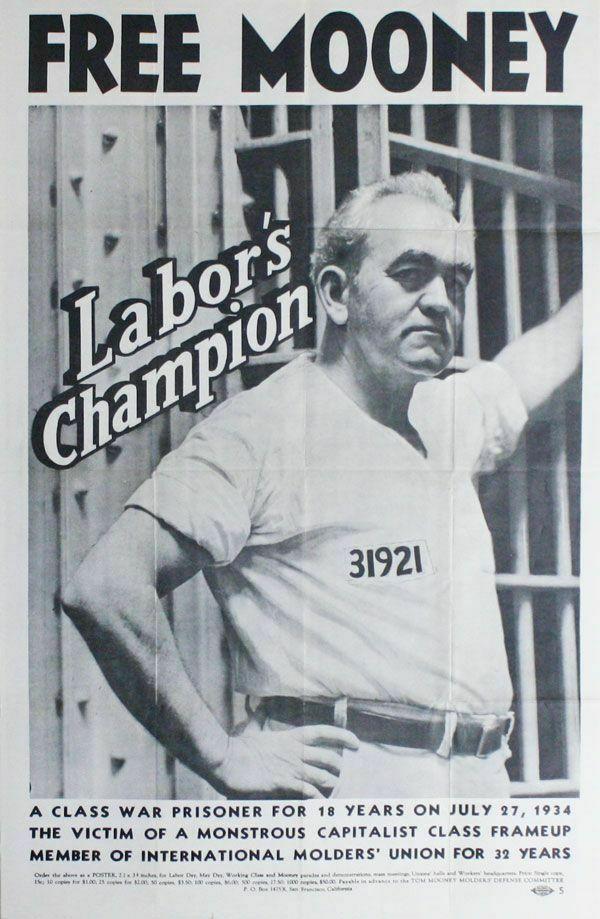

The urgent tone of a nameless reporter gives a sense of the epic scope and notoriety of Mooney's case at the time, though his story has since been eclipsed in the public’s memory by the lore of other activist movements. Here, he is referred to as "one of the most famous prisoners of all time," and though the day’s outcome was all but certain, the coverage is breathless.

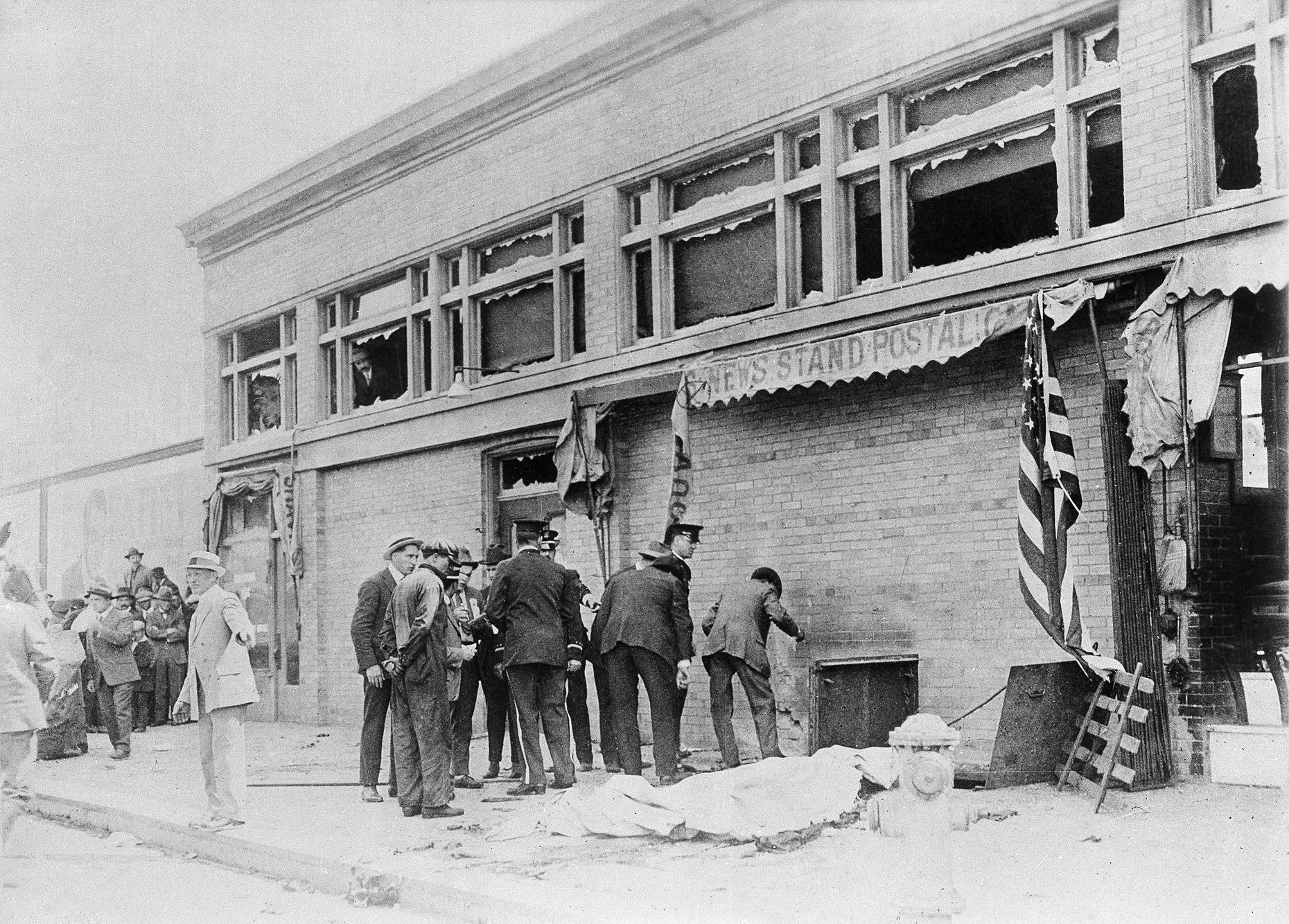

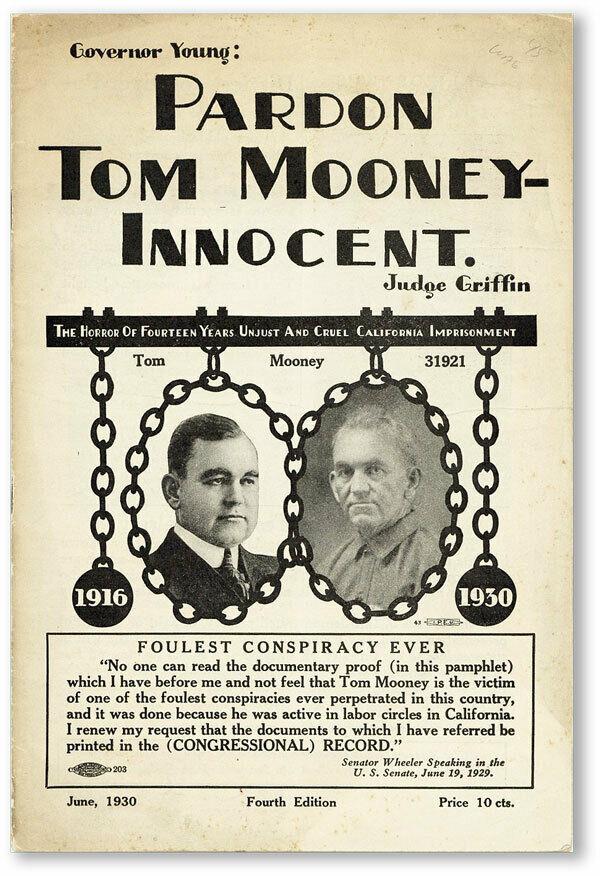

Accused of setting a bomb that killed 10 people and injured 40, Mooney was later proven to be elsewhere at the time. His trial was a sham in every detail, a fact that inflamed the left, adding to the country’s already explosive labor disputes. This prompted President Woodrow Wilson to begin a letter-writing campaign to the governor of California, William D. Stephens, less than a year after the sentencing, asking him to review the case. His pleas were ignored until the Supreme Court’s refusal to hear an appeal led to further outcry, and two weeks before Mooney's scheduled hanging, Stephens abruptly commuted the sentence, granting Mooney neither a new trial nor a pardon, leaving him to spend half of his adult life in prison. By the time of this broadcast, such facts had turned Mooney over the course of a generation into a figure so storied that the reporter’s description of his physical presence approaches hagiography:

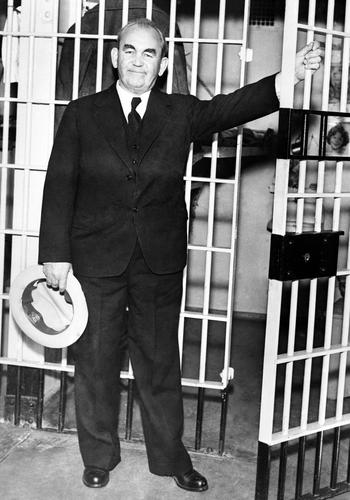

"Tom Mooney has already entered the [Sacramento] Assembly chamber and is seated directly in front of me….he appears here…past middle age, but still standing erect. His face is lined with wrinkles like that of any other man of 56. His hair has turned slightly gray and he wears glasses. But he’s smiling happily and appears full of spirit and eagerness…,” an apt description, judging by a photograph of Mooney, most likely taken the day of this broadcast, showing a well-coiffed, impish man possessed of the broad, open smile of the just.

After the governor, Culbert Olson, officially opens the proceedings, he invites any last objections to the pardon, then pauses for a dramatic and meaningful seven seconds before officially acknowledging the absence of any, and handing over the floor to Mooney’s lawyer, George T. Davis, who makes an impassioned speech. After this, Olson issues the pardon, preceded by an account of the case’s tangled legal history.

Thomas Joseph Mooney was born in 1882 into a Socialist family in Chicago. His father, Bernard Mooney, was a coal miner who died of silicosis at the age of 36, when Tom, the eldest of three surviving children, was 10. A militant organizer, his father was once left for dead at the hands of anti-unionists.

As a young man, Mooney studied Socialism in Europe and at home, holding many industrial jobs before emerging as an organizer and activist in San Francisco, where he married Rena Herman and joined the Socialist Party of America, and, briefly, the Industrial Workers of the World. In 1912 he became the publisher of The Revolt, a popular Socialist newspaper. The following year he was framed by the anti-union detective Martin Swanson, the first of several attempts by Swanson to hinder the organizer’s activities. Mooney soon became one of the leaders of the California Federation of Labor and attempted to unionize the streetcar workers of San Francisco’s United Railroads.

He was a powerful force in the city’s labor movement in 1916 when he was arrested along with his wife and three associates for the fatal July 22 bombing of a jingoist rally called the Preparedness Day Parade. Swanson was quickly appointed to investigate the case by District Attorney Charles Fickert, whose election had been secretly funded by the head of United Railroads. (Fickert had immediately dismissed corruption charges against Swanson upon taking office.) Of the five defendants, Mooney was the only one sentenced to death.

Perjury, corruption, suppression of evidence, conflict of interest, and other irregularities, facts studiously ignored by the prosecutors, five California governors, and every court to which they were brought. Deputy District Attorney Edward Cunha later told an interviewer that even if “every single witness that testified against him had perjured himself…I wouldn't lift a finger to get him out.”

Within weeks of the sentence, the first evidence of a mistrial began to emerge, and the case’s judge, Franklin Griffin, demanded a review. He is quoted here by Davis as calling the trial “one of the dirtiest jobs ever put over, and I resent the fact that my court was used for such a contemptible piece of work.”

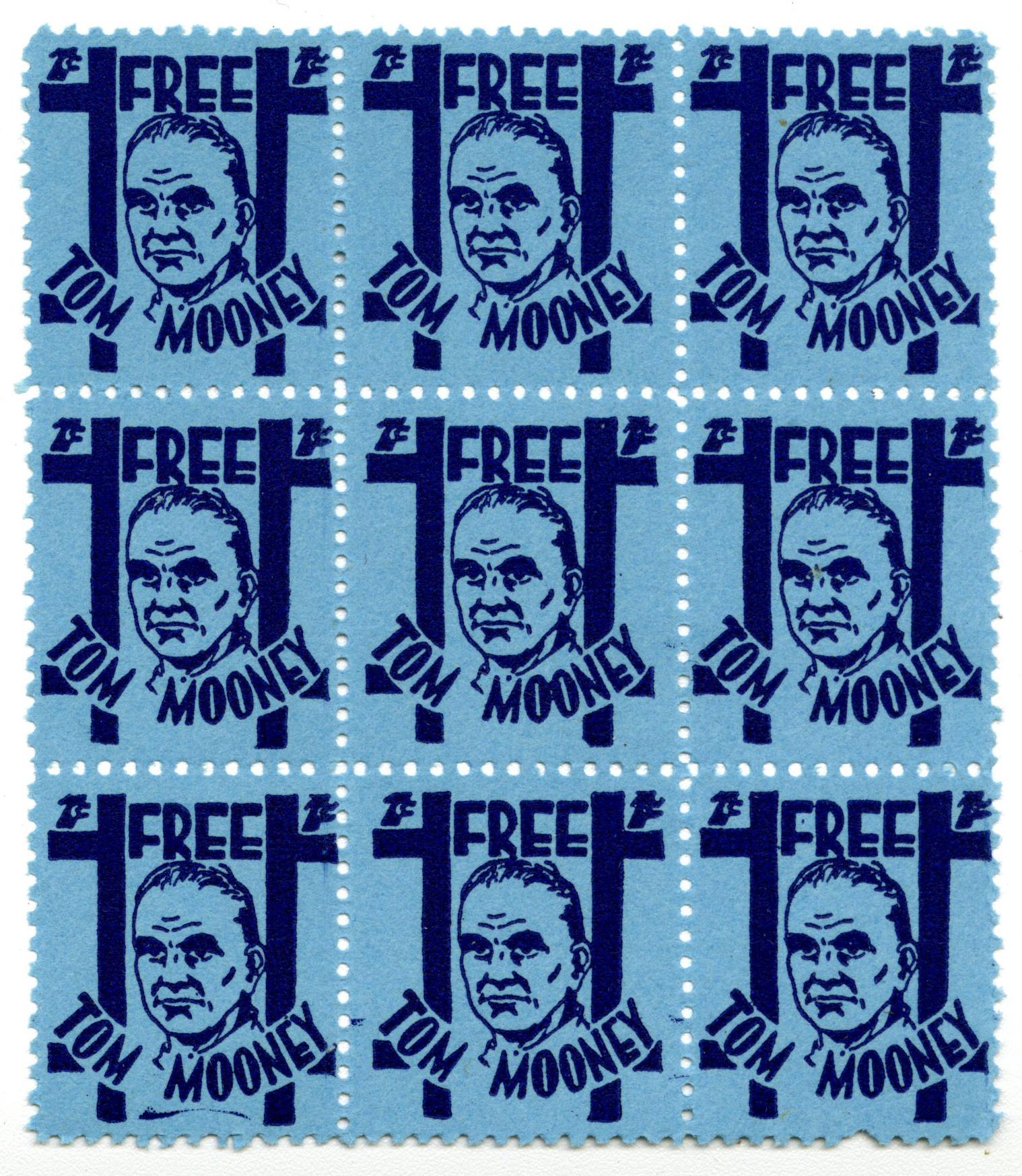

After a brief stay, Mooney was scheduled to be executed on December 13, 1918, but by mid-November, the end of the World War I, combined with the left’s mounting Free Tom Mooney campaign, had turned the West Coast into a powder keg of labor unrest. Even William Randolph Hearst, whose newspapers had campaigned for Mooney’s death, reversed himself, saying it should not take place. When a secret federal investigation proving the case a mistrial was leaked toward month’s end, and Governor Stephens refused to grant a new trial or a pardon, unions, especially Seattle’s -- the nation’s most radical -- took the opportunity to galvanize workers for one of the most important general strikes in the nation’s history.

Mooney's supporters included George Bernard Shaw, Heywood Broun, Samuel Gompers, Eugene V. Debs, John Dewey, Norman Thomas, Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, Sinclair Lewis, H.L. Mencken, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Emma Goldman, and Carl Sandburg. In a 1935 survey, he ranked as one of the four best known Americans in Europe (along with Franklin D. Roosevelt, Charles A. Lindbergh, and Henry Ford).

In his plea, Davis calls Mooney’s conviction “a blot on our courts and governors.…,” and the legal red tape that denied him a retrial a “preposterous quibble.” He calls for the pardon not only “as a redress with tragic tardiness, but… to vindicate California and clear its name before the world.” He also demands legal reform. His summation, delivered in incantatory cadences, makes use of mighty pauses to infuse each phrase with power:

Truth is mighty,

and shall prevail

in the pardon of Tom J. Mooney,…

Clear-sighted Americans

will recognize in [it]

an act of conservativism in the best sense of that word:

a conserving of the principals essential to free institutions

and the confidence of Americans in their own form of government.

Mooney’s pardon was celebrated with a parade up Market Street, accompanied by an honor guard of 100 longshoremen. An appearance later that year at Madison Square Garden was sold out. But Mooney’s years in prison had eroded his health, and a planned lecture tour was short-lived. Within 18 months of being pardoned, Mooney was bedridden, though he continued to campaign for the causes he believed in. Citing his politics as too radical, the California Federation of Labor turned down a resolution to pay his medical bills. Mooney died on March 6, 1942.

The year before, when the artist Anton Refregier was commissioned to paint a WPA mural depicting the city’s history for San Francisco’s Rincon Postal Annex, he chose to devote one of its 27 panels to Mooney’s ordeal. This image, among others, prompted much controversy, including an American Legion spokesman’s Congressional testimony that such panels should be removed because they “do not reflect the romantic and inspiring history of California,…[and are] depressing." In 1979 the mural was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Mooney’s case has also inspired the publication of at least a dozen books and pamphlets, and it is a staple of most general accounts of U.S. labor and legal history.

The WPA Federal Theater Radio Division 1938 edition of This Was News, The Tom Mooney Case.

Audio (at top) courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

Note: Some poor audio quality due to original recording.