On a recent Friday night in Times Square, dozens of people waited outside of Foot Locker. Amid the pulsing lights and swirl of human activity, those in line, mostly young men, stood still, or sat in camping chairs, sipping Big Gulp sodas, and waited patiently.

“I call them Jordan’s children,” said a Foot Locker worker patrolling a line, which stretched past Toys R Us and around the corner of 44th Street. “They’ll do whatever to get them Jordans.”

On this night in April, Air Jordan Playoff 12 sneaker went on sale, for $173 (with tax). Foot Locker re-opened its doors at midnight for the occasion.

Every week in New York there are a sneaker releases like this, though only the very largest draw attention from outside the community of people calling themselves “sneakerheads.”

But among sneakerheads, the hype over new shoes is so great that some entrepreneurs have discovered it’s possible to make a living flipping shoes: waiting on long lines to get a sneaker before it sells out, and then re-selling it at a significant mark-up.

Flipping Kicks

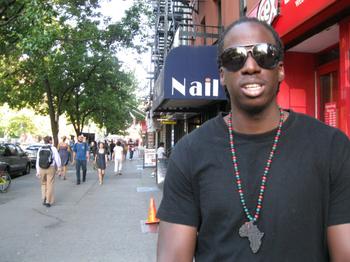

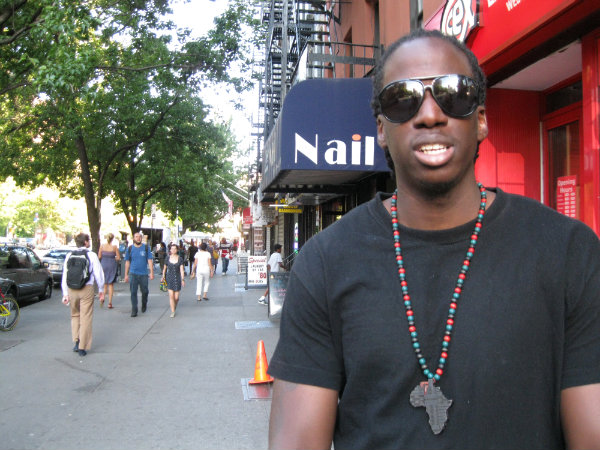

Tony Holmes was one of the people waiting in line on the night of the Playoff 12 release. But the Gucci sunglass-wearing 25-year-old wasn’t buying for himself. Holmes hoped to resell the shoe for $250 to $300.

“Even if I make $50 a pop, if you make a little bit of profit off of each sneaker, the goal is to get them in quantity,” said Holmes, who worked as a re-seller for the past two years.

The recently released limited edition Kanye West Yeezy II shoe (approx $245 in stores) now sells for $2,000 and up on eBay.

The recently released limited edition Kanye West Yeezy II shoe (approx $245 in stores) now sells for $2,000 and up on eBay.

To grow his profits, Holmes routinely hires a half dozen or more young friends to help him buy shoes, and circumvent the one-per-person policy that most stores strictly enforce. They can wait in line for hours, or even days, to get to the cash register. Friends hold each others’ place in line for bathroom breaks, and sometimes even so they can go home and sleep.

Re-selling shoes is legal, as long as the reseller collects and remits taxes to the government. Retailers and manufacturers know about this secondary market, and they tolerate it.

But why not raise prices to what the market will bear?

“There’s no set price, there’s a suggested retail that you work with all the manufacturers on,” said Chris Santaella, vice president for footwear for Foot Locker. “We will always be at the suggested retail to keep up a good relationship with our consumer.”

Nike, the leading maker of basketball shoes, did not offer comment, but many analysts believe the company has learned to harness the hype.

“The concept of unrequited demand is paramount with Nike when they think about shoes,” said Matt Powell, a retail analyst with SportsONESource. “I think they always try to keep the supply below demand level. They want the shoes to sell out in a relatively short time because that creates excitement for the next one around.”

Sneaker Reseller is not a category recognized by the Bureau of Labor statistics, and there are no reliable figures for how many people do it, or the size of the secondary market.

Americans spend about $20 billion a year on athletic shoes, Powell said, but basketball sneakers are only a small, if lucrative part of it.

Becoming a Reseller

Becoming a Reseller

For Holmes, the work affords a good quality of life. He makes his own schedule, and has his own apartment on the Lower East Side.

He became a reseller by accident after his 21st birthday. Holmes’ father, who’d never been around much, gave him a birthday gift: an iPod classic.

But it was the wrong device: Holmes wanted an iPod touch. So he sold the classic on Craigslist, made $140, and bought the iPod touch.

“Then I said, ‘Wait, I could make money off of this, and I started buying a reselling iPod touches’,” said Holmes. “And then I ran into people doing the same thing, but they did cell phones. With cell phones, you make more money.”

Soon, Holmes was buying and re-selling sneakers.

Today, he mainly sells shoes through a consignment shop, because it’s less hassle than Craigslist. But Holmes also has word-of-mouth customers.

Recently, Tony Sewell, a bike store manager, met Holmes on East 14th Street to purchase a pair of Air Jordan 4, Knicks edition (in blue and orange), for $250.

“I went to the store to go grab these, and then the guy’s like, ‘Yo, Tony bought ‘em all,’” said Sewell, a first-time customer.

Why fork out so much for sneakers?

“It’s partly a childhood thing,” Sewell said. “And now that I’m older, have a better understanding, now I can actually afford these things. We tie a Faberge egg-ish element to a lot of things in life.”

The Rules Changes, The Game Remains

Re-selling sneakers is nothing new. Athletic shoes have been a collectible at least at least since the first Nike Air Force 1s and Air Jordans came out in the 1980s. But the internet and cell phones are lowering barriers for people with the right combination of skills.

Holmes says you only need three things to excel: time, patience, and money.

“You gotta have money to pay people to wait online to actually get the sneaker,” Holmes said. “Time – you gotta be able to say, ‘Yo, I’m gonna wait on line for a week.’ A lot of people can’t afford to do that. Patience. You gotta have patience to wait outside and wait for the sneaker to come out.”

The night the Playoff 12’s dropped, Foot Locker didn’t open its doors till well after midnight. At 1:30 a.m., Holmes was still far back in line, and Foot Locker was only admitting a few buyers at a time. Holmes said his next destination wasn’t bed; it was another shoe store that opened its doors at 7 a.m.

Photos by Stephen Nessen.