NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

Scottsboro: A Civil Rights Milestone

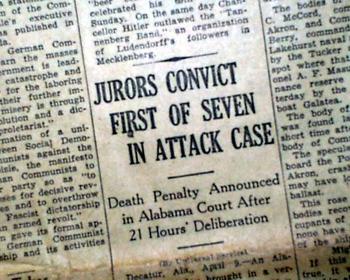

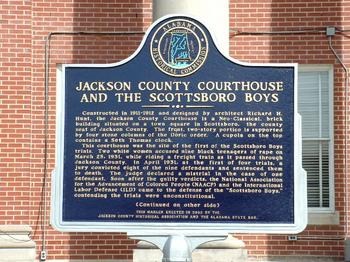

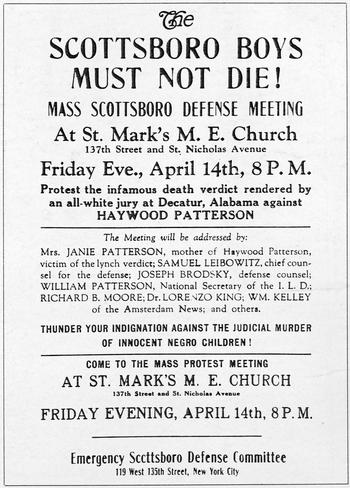

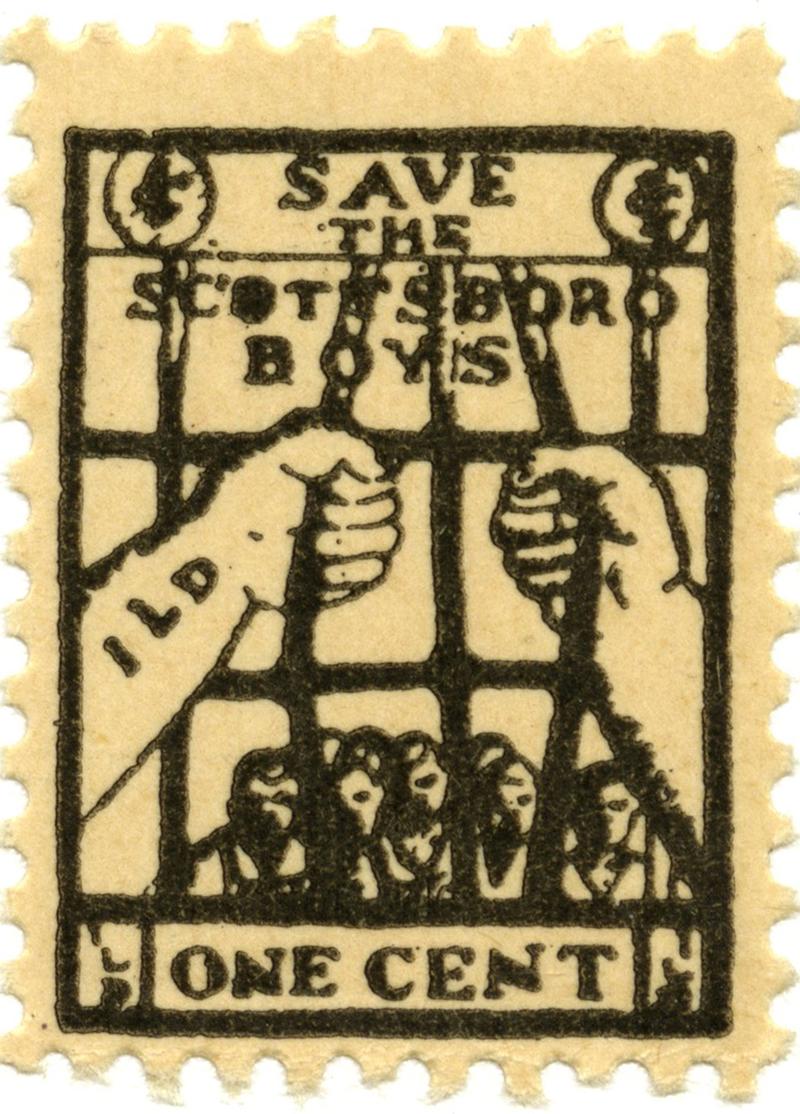

It was the Great Depression. Nine young black men were hoboing, riding a freight train to Memphis, Tennessee in search of work, but their ride was cut short. At Scottsboro, Alabama the police hauled them off the train: the young men, ages 13 to 21, were accused of raping two white women who were on the train. For black men in the 1930s in the Deep South, such a charge could be fatal. Like so many others who had died by trial or lynching, the Scottsboro Boys (as they came to be called) were falsely accused, a fact that meant almost nothing. In March 1931 eight of them were sentenced to death, while the fate of the ninth, 13-year-old Roy Wright, hovered dangerously close to life in prison before ending in a mistrial.

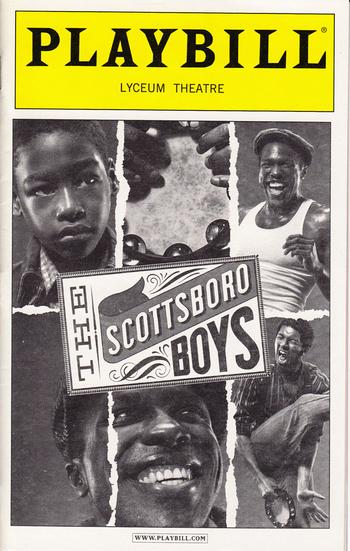

The case of the Scottsboro Boys (Charlie Weems, Willie Robeson, Olen Montgomery, Ozzie Powell, Eugene Williams, Roy, and Andy Wright, Clarence Norris, and Heywood Paterson) became a worldwide cause célèbre, a symbol of American injustice. Although they were not put to death, altogether the Scottsboro Boys spent more than 100 years in jail for a crime they did not commit. While the case is a largely forgotten landmark in American civil rights history, for many, blacks and whites, the Scottsboro Boys and memories of those times in the South remain vivid and indelible.

As far as Scottsboro's impact on the law is concerned, there were two major U.S. Supreme Court rulings in this case: one upheld a defendant's right to effective counsel under due process; the other prohibited the exclusion of jurors based on race. These two decisions were effectively the first substantive legal efforts undermining the climate of fear and intimidation that reigned over African-Americans in the South --what historian James Goodman simply calls "southern injustice": "To know that [type of] injustice as black people knew it, it was necessary to know it in the parts of the body that produce nausea, chills sweat, and tears, to have it knock the wind out of you and triple the beat of your heart..."[1] In his compelling 1994 work Stories of Scottsboro, Goodman goes on to write:

Knowledge of southern injustice came in part from fear of it; and fear came from the knowledge that the color of your skin made you a suspect--a suspect that looked just like the prime suspect--every time the police were looking for a black man. It came from knowledge that if arrested, you were likely to be subject to the third degree; if indicted, you were likely to be unrepresented; if convicted, sentenced to a longer term in prison or on the chain gang than a white man convicted of the same crime. The fear came from the near inescapability of the danger, the sense that no matter how careful and deliberate your every expression, word and deed, no matter how unblemished your past, how fine or widely recognized your reputation, no matter how prosperous you were or how well placed, no matter how unshakable your alibi, you were not immune from false accusation, mistaken identity, wrongful conviction, and punishment.[2]

This audio documentary takes a look at that injustice through the voices of some of the people who were involved in the Scottsboro case, including defendant Clarence Norris, as well as those who have studied the case. The program was produced and narrated by Andy Lanset. It was originally broadcast by WNYC and the NPR Horizons series in 1992.

Special thanks to Donna Limerick, CBS Archives, Gary Daughters, Leonard Lopate, David Rapkin, and the late David Nolan, with engineering by Manoli Wetherell and Neal Rauch at NPR in New York.

The nine Scottsboro defendants with National Guardsmen outside of the Scottsboro jail, March 26, 1931, the day after they were arrested. From left to right: Clarence Norris, Olen Montgomery, Andy Wright, Willie Roberson, Olin Powell, Eugene Williams, Charlie Weems, Roy Wright and Haywood Patterson. (© Bettmann/CORBIS/Corbis Images)

[1] Goodman, James, Stories of Scottsboro, Vintage Books, 1995, pg. 248.

[2] Ibid.

An Original Radio Newsreel Report on the Scottsboro Case in 1932

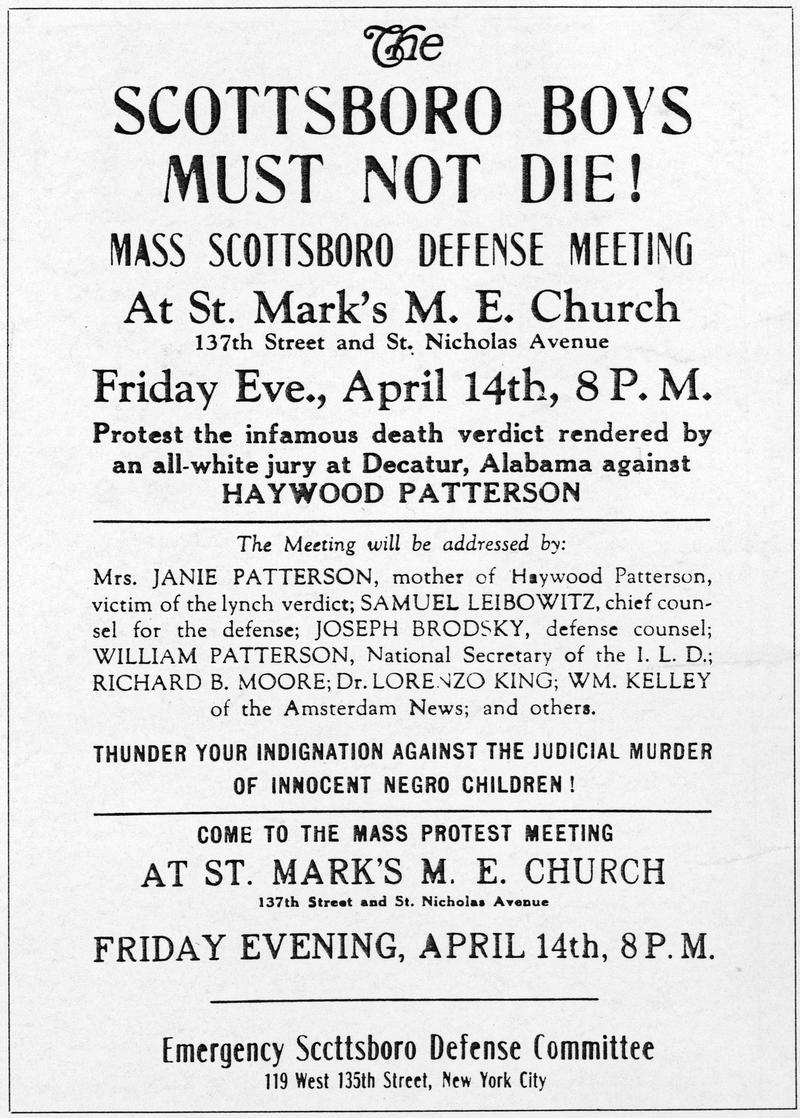

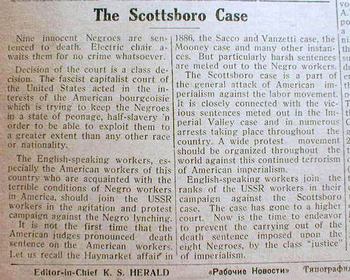

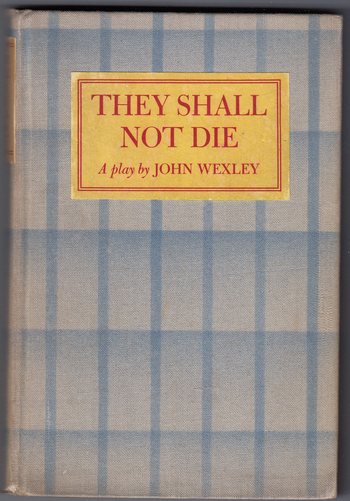

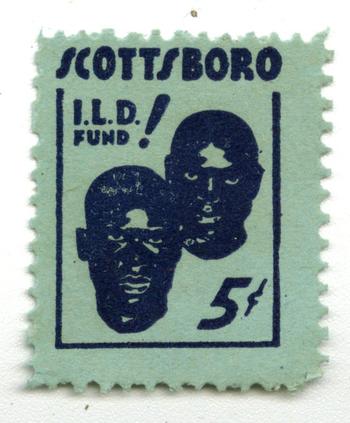

In the early 1930s many radio stations broadcast syndicated radio newsreel programs like The March of Time and The News in Review. Because the programs largely pre-date the widespread availability of truly portable recording equipment, these early 'news' shows were typically reenactments or dramatizations of the week's leading news stories, and were often a bit sloppy when it came to the facts and journalistic standards. In this rare November 20, 1932 episode of The News Parade broadcast over WMCA in New York, the Scottsboro case is brought up through the first of its two U.S. Supreme Court decisions, concluding with the dramatization of a Communist Party demonstration on the steps of the Capitol in support of a fair retrial for the Scottsboro defendants.

____________________________

See also: The University of Alabama archive on the Scottsboro Case.

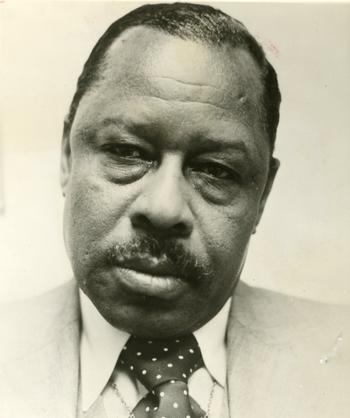

In 1979 Clarence Norris, the last surviving of the Scottsboro defendants, were interviewed by Casper Citron. He was joined by writer Sybil Washington, with whom he had collaborated on the book, The Last of the Scottsboro Boys