NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

Marcus Garvey: 20th Century Pan-Africanist

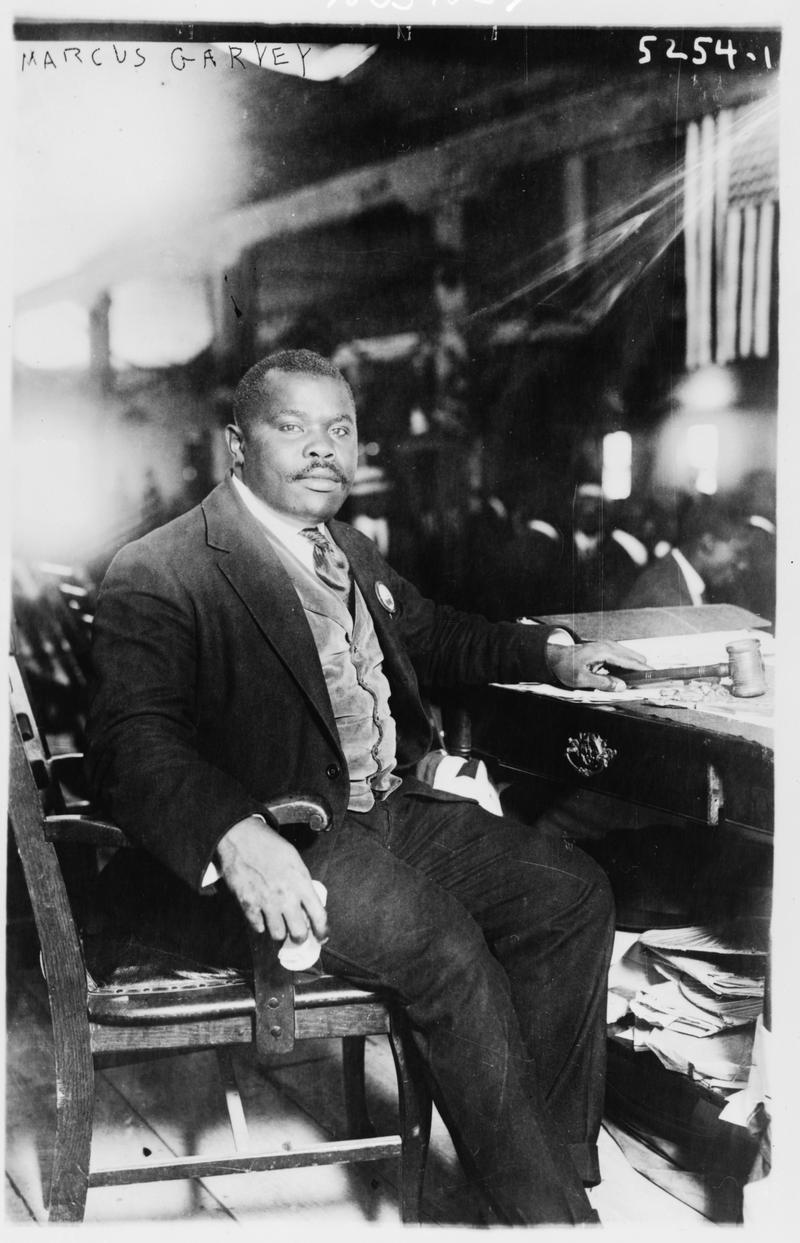

( George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress / Library of Congress )

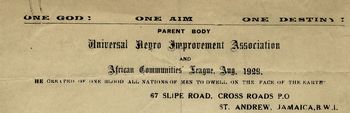

Marcus Garvey, the promoter of Pan-Africanism and black pride, had a vision of economic independence for his people. Those who followed him were called Garveyites. He was the founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, (UNIA) the single largest black organization ever. In the 1920s and 30s, the UNIA had an estimated six million followers around the world.

Marcus Garvey came to this country from Jamaica in 1916. His efforts to 'uplift the race' through the free enterprise system were met with skepticism, ridicule, and even sabotage. In 1927 he was deported from the United States as an undesirable alien. In the passing years, there has been a renewed interest in Garvey reflected in books, music, and attempts to clear his name.

In this 1992 documentary, I take a look at Marcus Garvey, the man whose legacy has influenced black activists and organizations for almost a century. We hear from Garvey's sons, Garvey scholars, and those who followed him. But first, we hear from Garvey himself in his only known recording made in the summer of 1921 after a long tour of the Caribbean and Central America. Listen in.

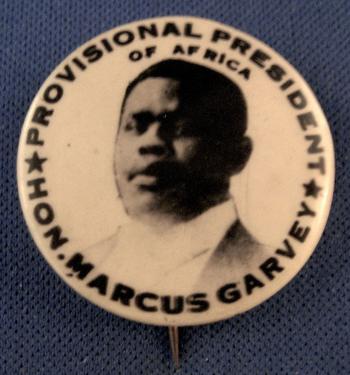

Marcus Garvey, then head of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and provisional president of the Republic of Africa, rides through Harlem. (New York Daily News Archive via Getty Images). _________________________________________________________

This documentary first aired on the NPR Horizons series and was broadcast on WNYC in 1990. Special thanks to David Rapkin, Steve Shapiro, and Brian Glassman. With Engineering by Spider Ryder, the program was edited by Donna Limerick with production assistance by Eileen Ellis.

In this documentary, you hear the singing of Amy Gordon, a veteran member of the UNIA who hailed from Jamaica and remembered some of the organization's songs. They are reproduced -to the best of her memory - below from my original field recording.

UNIA Song 1

UNIA Song 2 - Father of Our Great Nation

UNIA Song 3 - Oh Shine On Eternal Light

UNIA Song 4

Marcus Garvey:

It is for me to inform you that the Universal Negro Improvement Association is an organization that seeks to unite, into one solid body, the 400 million Negroes of the world for the purpose of bettering our industrial, commercial, educational, social, and political conditions.

Speaker 2:

Marcus Garvey organized the Universal Negro Improvement Association or UNIA at a time when the future for black people looked grim. In Africa, the final touches of the European conquest were being put in place. In the Caribbean, poverty and the lack of educational opportunity compelled tens of thousands to leave the islands in search of a better life. And in America, the civil rights gains of reconstruction had been wiped out, aided and abetted by state legislatures and an indifferent federal government. It was a time of growing racial repression and social unrest.

Dr. John Clark:

[inaudible 00:00:53]

Speaker 2:

In 1917, an anti-black pogrom Hiti St. Louis. Two years later, there were race riots in 25 US cities and towns. In Chicago disturbances left more than 500 injured and 38 dead. A long dormant. Ku Klux Klan was revived and gaining in popularity. Lynchings were on the rise. According to historian and Garveyite, Dr. John Henry Clark, blacks were ready for a man like Marcus Garvey.

Dr. John Clark:

Following World War I the black soldiers returning and blacks and whites fighting over the scarcity of jobs. New DeBaker secretary wall would tell black soldiers that you will not appreciably change because you fought in the war and you would have the riots in East St. Louis. America was saying to us verbally and physically, but we accept your labor. We are not ready to accept you as citizen. Now you can see how the message a Marcus Garvey coming at this time of despair would attract so many people.

Speaker 2:

The goal of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association was the total emancipation of blacks from white domination. This included the creation of black businesses and schools, the uplifting of blacks as a race wherever they lived, and the establishment of a separate black homeland. Sixty-year-old Marcus Garvey Jr. is a proponent of his father's philosophy and today is President of a UNIA chapter in New York.

- Garvey Jr.:

The aim of Marcus Garvey was to create a great central nation in Africa that would be so powerful and strong that it could protect Africans all over the world. But Marcus Garvey's great achievement was to make this idea understandable to the masses of African people.

Speaker 2:

Before founding the UNIA, Garvey had been a printer and union leader in Jamaica. There he had struggled with little success against white landowners and shipping companies to improve the life of Jamaican blacks. Inspired by Booker T. Washington's autobiography "Up From Slavery." He saw a black self-reliance in education and business as key to his agenda. Garvey was convinced blacks had no secure place in America, that ultimately the United States, like Britain and other European countries, was a white nation where people of African descent would never be able to determine their own fate. For Marcus Garvey, the answer boiled down to a potent slogan.

Marcus Garvey:

We hear the pride of England for the Englishman, of Germany, for the Germans, of Palestine for the Jews, of China for the Chinese.

Marcus Garvey:

We of the Universal Negro Improvement Association are raising the cry of Africa for the Africans, those at home and those abroad.

Marcus Garvey:

There are 400 million Africans in the world who have Negro blood coursing through their veins.

Speaker 2:

Marcus Garvey was dark, short, stout and proud. He was married twice. Amy Jacques Garvey being the mother of his two sons, Marcus Jr. And Julius. For more than 25 years, Garvey's voice thundered through meeting halls, packed with his followers. They were former slaves, war veterans and workers. Never before had they heard such talk of the United States of Africa, of black dolls for their children to play with, of a black Christ, for them to worship of, in Garvey's words, one God, one aim, and one destiny for African people.

Marcus Garvey:

You need to take up their medication.

Audley Moore:

Oh, he talked about Africa. He talked about how Africa was raped, all her wills, I was stolen. He told about Africa's children who were kidnapped and that Africa had lost more than a hundred million people in that slave trade and I was very impressed with that.

Speaker 2:

Ninety-two year old, Audley Moore, known affectionately in Harlem as Queen Mother Moore, has been a political activist and Garveyite nearly all of her life. She remembers when she first saw Marcus Garvey at the Longshoreman's Hall in New Orleans. It was July 15th, 1922.

Audley Moore:

Everybody had guns. It's 44s, 38 specials, and a bag of ammunition. And when Mr. Garvey came in, he apologized for not being able to speak to us the night before. And he said, the mayor permitted himself to be used as a stooge for the police department prevent me from speaking. And the police, they had filed in the hall. They jumped up on the platform, said, I'm going to run you in for saying that. And everybody jumped up on the benches, took our piece out, held it up in the air, say, speak off his speak. And Garvey said, and as I was saying, and then the police filed out of the hall like little puppy dog, the little tails behind them, they just were so... All of them turned red, red. I saw them red turned red, all those white people turned red. And they filed out of there.

Speaker 2:

No other leader had given poor and working class blacks such hope and pride. They rallied around the UNIA flag, a tri-color of red, black and green. The red symbolizing African blood shed in the name of redemption and liberty, black for the color of a noble and distinguished race, and green for the fertile African soil. And then there was Garvey's motto. "What other men have done, we can do." It was heard all over Harlem where the universal Negro Improvement Association had its headquarters. There were also UNIA restaurants, shops, storefront factories, a printing plant, and a newspaper, The Negro World.

Amy Gordon:

Then you found The Negro World. Have you heard the Negro scal? Oh, are we speaking to one? Very clear and so on. That is the day he's dry in the nigh. Every day, hymn chant and I will wake family asleep, and stand like men right under the flag. How's it red, black and green? Richard Garvey is the black man whom..

Speaker 2:

Seventy-one year old Amy Gordon is a member of the Brooklyn division of the UNIA and one of the few who still remembers the organization's early hymns. As a young woman in Jamaica, she embraced Garveyism, seeing in it the way to liberation for African people. Often she stood on Kingston street corners preaching the gospel, according to Garvey, before crowds of rapt listeners.

Amy Gordon:

It time has come that the black man was forgetting cast behind him as you are worship and adoration for the races and start immediately to create and emulate one of his own. We must canonize one same creator on marches and elevate to position of fame and a black man and woman will immediately gain contribution to our racial history.

Music:

[Music]

Speaker 2:

As a fraternal organization, the Universal Negro Improvement Association held huge conventions and elaborate parades with black cross nurses who aided the sick and an African Legion dressed in smart military uniforms. Riding in an open limousine, Garvey to could be seen in a gold-braided uniform with tassels wearing a plumed hat like some latter day Napoleon. Charles Lionel James is President General of the UNIA now numbering only a few thousand members with branches in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Chicago, Detroit, Montreal, and Southern California. In 1922, he ran the UNIA's New York Juvenile Branch.

Charles James:

I had my Brigadier general uniform. It was a black uniform with a red stripe pants and cap. And to be truthful about it, when I was in my uniform, I was transformed in a way I didn't think it though was ordinary. It had no... Yes, that the uniform meant so much to me.

Speaker 10:

Countrymen, You’d better get on board. Six steam ships want to sail away, Loaded with a heavy load. It’s gonna take us all back home, Yes, every native child. And when we get there, What a time Down on the West Indy isle. Get on board The Countryman, Get on board to leave this land. Get on board The Countryman, Come along, 'cause the water’s fine.

Speaker 2:

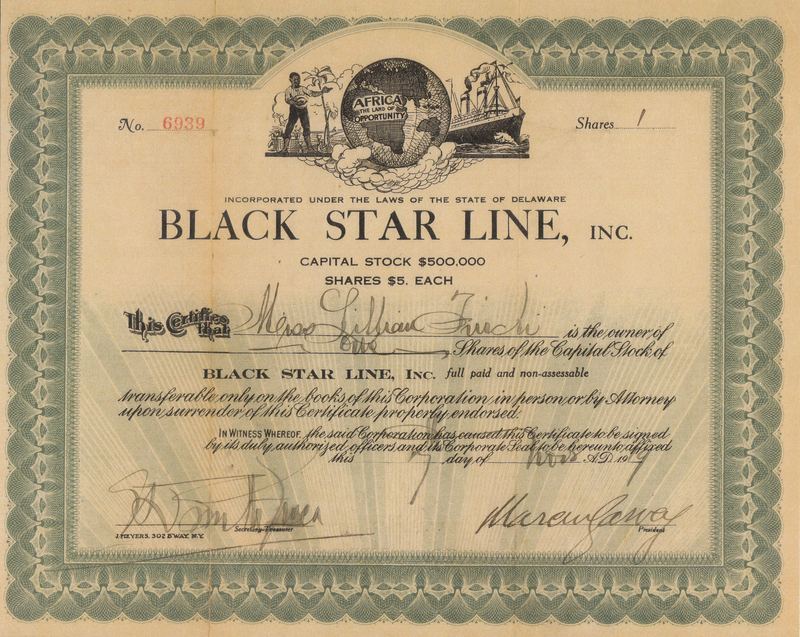

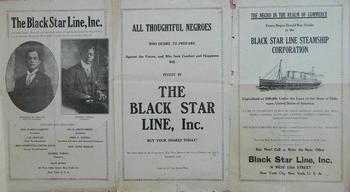

In 1919, Garvey founded the Black Star Line, a steamship company whose goal was to serve a triangular trade and passenger service between West Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States. Goods produced by Garvey's Negro factories corporation, a manufacturer of products by and for blacks would be shipped on the line and skilled African Americans would find easy passage, at least initially, to Liberia for the purpose of nation building.

Speaker 10:

Get on board The Countryman, Get on board and leave this land, Get on board The Countryman, Flying home on the Black Star Line

Speaker 2:

Marcus Garvey's vision of an African Homeland began with Liberia. The continent's first independent Republic, founded as a colony for freed African American slaves in 1821. The Liberian government, in a sense, remained true to its original mission and welcome the UNIA to its shores. Marcus Garvey-

Marcus Garvey:

That all Negroes, all over the world, are working for the establishment of a government in Africa, means that it will be realized in another few years. Our race, this organization, has established itself in Nigeria, West Africa, and it endeavors to do all possible to develop that Negro country to become a great industrial and commercial commonwealth. Pioneers have been sent by this organization to Nigeria, and they are now laying the foundations upon which the four-hundred million Negroes of the world will build.

Speaker 2:

The Liberian government's welcome soon gave way to alarm with a release of a confidential UNIA report from the field critical of the country's leadership. The documents suggested to Liberian officials that Garvey's African settlement plans were simply prelude to a coup. They rejected all UNIA efforts and then signed an agreement with the Firestone Rubber company, leasing land for rubber cultivation. That included parcels once promised to the UNIA. Meanwhile, the British and French governments maintained consistent covert efforts against Garvey since they had neighboring colonies and could hardly be considered sympathetic to a black nationalist movement.

Charles James:

So it was easy for them to form a coalition to destroy Marcus Garvey.

Speaker 2:

Charles Lionel James.

Charles James:

And the coalition consisted of lies and first thing they had to do was to build up Marcus Garvey as an agent that he was out to steal, that he was out to fatten his own pocketbooks and so forth. So that was the day, those things were, were created out of the mouth of individuals who didn't mean our race any good.

Speaker 2:

The Liberian colonization effort was popularized by the white and black press as a back-to-Africa movement and nowhere except in Garvey's newspaper, The Negro World. Was there any discussion of how Liberia fit into the UNIA's overall program for economic independence and Pan-Africanism? Yet this popular view and image of mass immigration to a homeland in Africa was by itself a powerful message for blacks seeking an escape from oppression and poverty. Amy Gordon-

Amy Gordon:

When we reach the golden shore we shall be uppy and free. Oh, from Marcus Garvey we'll be there as uppy as uppy can be. Oh, the UNIA, UNIA. This is the best thing for black men today. Follow our leader and brightens the way, God bless the UNIA.

Speaker 2:

Through the early 1920s, Garvey raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for The Black Star Line with the sale of stock, which the UNIA said was limited to members of the Negro race. So even the poorest Harlem resident could buy a share for $5 and feel he or she was working for the betterment of blacks everywhere.

Speaker 2:

Between 1919 and 1925, five secondhand ships were purchased with the money. Despite popular support from the African American community, the steamship line eventually folded, a victim of employee theft and sabotage. And according to Garvey scholar, Robert Hill, there were other reasons.

Robert Hill:

Given the awesome complexity of running a merchant Marine. The undercapitalization of the venture. Inadequate technical expertise that black people could muster. I do not think that given these conditions they enterprise could have been successful.

Speaker 2:

Garvey's financial difficulties were far from his only problem. Opposition to the black leaders agenda came not only from Liberia and the colonial powers, but major black organizations as well.

Speaker 2:

Black labor leader, A. Philip Randolph believed Garvey's Africa would be a dictatorship, not a democracy. Black clergyman resented Garvey's African Orthodox church because it threatened to win over their parishioners and then there were the integrationists, the Communist party and the NAACP, whose chief spokesman W.E.B. Dubois said Garvey was the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race and either a lunatic or a traitor. Dr. John Henry Clark.

Dr. John Clark:

W.E.. Dubois, who believed the college bred black was the logical leader and he had this Jamaican who had not even decently finished high school announcing sweeping ideas that will literally change the social status, not only of black people, but it would change the social status of the world had it been put in motion and do was missing. How dare you think that you can carry off a scheme as big as this.

Speaker 2:

The personal animosity between Garvey and Dubois, though at times quite heated, was perhaps more than anything else, a manifestation of a more fundamental ideological battle between the two black leaders. Garvey scholar, Dr. Tony Martin describes the dispute as a continuation of the conflict Dubois had with Booker T. Washington.

Dr. Tony Martin:

The issues raised were largely the same. The question of economic self sufficiency, versus what some historians have called protests. DuBois was into that, so called protest school. The marches, the demonstrations, Washington prefer to take an easy on a protest under emphasize building an economic base. Garvey, in many ways,` was similar to Washington, although Gabby had a much more radical angle as well. But in many ways unsurprisingly, so Garvey was similar in many ways to Washington.

Speaker 2:

There was, of course, a more traditional enemy of black America, a common foe of both Dubois and Garvey, the Ku Klux Klan. Dormant since reconstruction, the KKK had been revived in 1915 and in just 10 years, it's estimated US membership was nearly 9 million.

Music:

Now, come on all you people that don't want hear. The story of a ganger that appears up there, no fair and they all hang together for they don't let them down the right name. For the mili-Ku Klux Klan.

Speaker 2:

The NAACP seemed helpless in the face of mob violence and race hatred. The UNIA, however, adopted a militant stand threatening to fight violence with violence. At the Klan's invitation there was a summit conference between Garvey and a leading Klansmen in Atlanta in June, 1922. The meeting prompted an avalanche of criticism against Garvey who defended the session saying, I was speaking to a man who was brutally a white man and I was speaking to him as a man who was brutally a Negro.

Speaker 2:

Many believed Garvey made,, at the very least a tactical mistake that as a Jamaican he did not understand the deep significance of what the Klan represented to African Americans. The meeting, even if meant as a sign of strength against the Klan, was instead widely interpreted as an endorsement.

Speaker 2:

Marcus Garvey Jr.

- Garvey Jr.:

My father made no mistake in meeting with the Klan. That's the American n***er mentality. And the Caribbean mulatto mentality at work. He went there to let them know, you don't mess with my people.

Speaker 2:

Because Garvey believed the clan represented the invisible US government. Professor Robert Hill suggests the black leader accepted the KKK's invitation to show white America that if it had an ally in the black movement, it was not his leading opponent, the NAACP, a group that favored integration, but rather the separatists UNIA.

Robert Hill:

In other words, he wanted to both diffuse white American hostility towards the UNIA and also diffuse the influence of his black opponents, his political enemies. It led him into I think, a very serious mistake and he did it without any consultation with his own movement, so that his own movement was split on that question and in politics. As you know, that's always a disastrous consequence.

Speaker 2:

Throughout the 1920s, Garvey maintained contact with white supremacists like Mississippi Senator Theodore Bilbo, Earnest Cox of the white America society, and John Powell, president of the Anglo Saxon clubs of America. Years later, the UNIA would work in support of Bilbo's 1939 Greater Liberia Repatriation Bill, a measure that called for the voluntary repatriation of African Americans to West Africa with assistance from the US government. While most unusual, professor Tony Martin believes Garvey's relationship with these white racists is easily misinterpreted.

Dr. Tony Martin:

Garvey believes in race first. He believed in concentrating, like Booker T. Washington, on building the black community integration for its own sake, was not high on his list of priorities. In that sense, Garvey was somewhat similar to Malcolm X later on, Elijah Muhammad and many others like that. He comes out of that tradition. It's a very ancient tradition in black America and as such, Garvey could have a symbiotic relationship there. That's what I've called it with the segregationists. Clearly, Garvey could not condone their racist expressions and so on. But insofar as they, in the separation at whatever level, and Garvey was in the separation at whatever level, it meant that in this one little area there were something around which they could sit down and discuss.

Speaker 2:

Hampered by foreign governments, scorned by the NAACP, undermined by the Communist party, garvey was also hounded by us authorities. The young J. Edgar Hoover, then head of the Justice Department's Bureau of investigation viewed Marcus Garvey as a foreign radical who was stirring up subversive sentiment among American blacks.

Speaker 2:

Garvey was placed under surveillance and the UNIA's headquarters were infiltrated with the aim of building a case for his deportation. In 1923, Garvey was tried for mail fraud in connection with the sale of Black Star stock. The trial became a bit of a sensation when early in the proceedings, Garvey fired his attorney, charging the lawyer was not working for his best interest. The black leader then defended himself, often in a flamboyant fashion. Charles Lionel James was in the New York courtroom. He remembers closing statements by Garvey and the government prosecutor.

Charles James:

Gentlemen of the jury says, Marcus Garvey, not only portray himself as a hero, but he portrayed himself as a tiger. And, and he said to the Jews, gentlemen, are you going to let the tiger ago? And Marcus Garvey, when he summarizes case, he says, gentlemen, you make age, the tiger. So, but there are thousands of cubs that are in the bushes that you haven't caught yet.

Speaker 2:

Despite the rather suspect evidence against him. The jury found Garvey guilty. He was sentenced to five years in prison. Out on bail, Garvey appealed, but lost in 1925 intense pressure for his release by UNIA chapters at home and abroad, along with an official desire to get him out of the country led president Coolidge to commute Garvey's sentence.

Speaker 2:

In December, 1927 he was deported to Jamaica. Two years later, factional fighting split the American UNIA from the parent body. And for the next 13 years, Garvey struggled to keep his organization and ideas alive, shuttling between Kingston, London, and Toronto. The UNIA's popularity declined. As a young stringer reporter, John Henry Clark went to Canada in 1938 to interview.

Dr. John Clark:

It was a very harassed man and very trouble and bitter. He did more complaining than anything else, complaining about the British empire and betrayed his promise to its colonial people. He promised improvement arguing with some of his borrowers who had not fathered it to him. A thing like $9 and 85 cents this rit, yet unpaid. To be reduced to that arguing petty things like less than $10 seem pathetic. This man who had raised millions and built the largest black organization before a sense. He wasn't civil and I was told that I should have met him in another time, in another place.

Speaker 2:

During Garvey's last years in London, he organized the school of African philosophy, which through correspondence courses as well as intensive classes taught by Garvey himself, prepared UNIA members for leadership roles in the organization. Active to the end, the 52 year old Garvey died in his London apartment of a heart attack on June 10th, 1940.

Speaker 13:

Garvey! Marcus Mosiah Lead thy people

Speaker 2:

Although poor when he died, Marcus Garvey left a rich and powerful legacy. He's considered to have been a keen influence on the Rastafarians of Jamaica, America's black power movement, the nation of Islam, Malcolm X, the African National Congress, and African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta.

Marcus Garvey:

If you believe that the Negro has a soul, if you believe that the Negro is a man, if you believe the Negro was endowed with the senses commonly given to other men by the Creator. Then you must acknowledge, that what other men have done, Negroes can do. We want to build up cities, nations, governments, industries of our own in Africa, so that we will be able to have a chance to rise from the lowest to the highest position in the African Commonwealth.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.