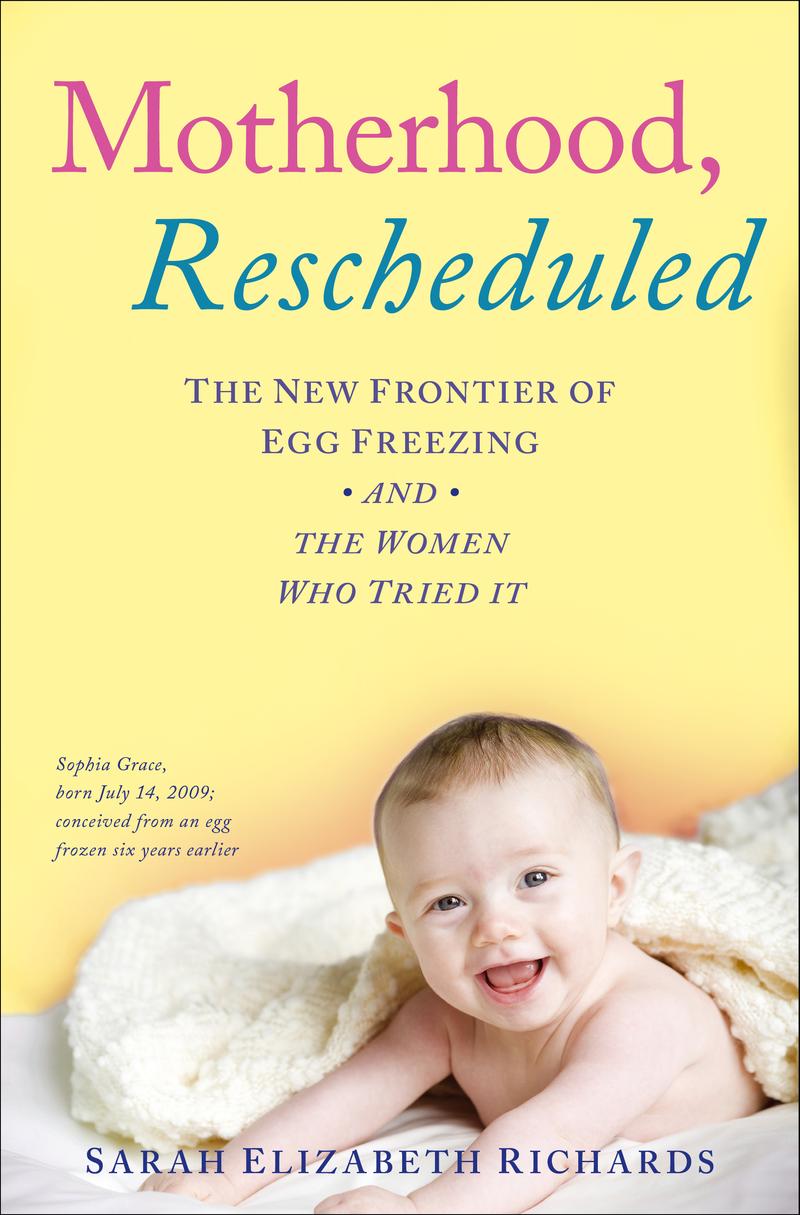

Sarah Elizabeth Richards, science journalist and the author of Motherhood, Rescheduled: The New Frontier of Egg Freezing and the Women Who Tried It (Simon & Schuster, 2013) explains the science behind freezing eggs and tells the stories of four women who tried it, including herself.

from: Motherhood, Rescheduled: The New Frontier of Egg Freezing And The Women Who Tried It

By Sarah Elizabeth Richards

Simon & Schuster

Introduction

There was one time in my life when I was grateful for the biological clock. I was thirty –two years old and summoning the courage to leave a relationship. After nearly eight years of living with a man I deeply loved, I wasn’t miserable. I just wasn’t happy.

We had been doing the stuff advice books say you’re never supposed to do. We punished each other with silence, criticized each other’s driving, made separate holiday plans, argued in public, and butted heads so fiercely about meals, budgets, sex, housework, exercise schedules, movie choices, and vacation destinations that it became easier to spend most of our free time apart.

We tried the standard fixes: we went to couples counseling, swapped lists of behaviors we were willing to change, and spoke in “I feel” statements. There were brief improvements, but the tension always returned, and I became increasingly certain that I did not want children with him. How could we agree on how to take care of another human being if we couldn’t decide when to do laundry? I made sure never to miss my birth control pills.

I knew we had no future, but I also felt no urgency to overturn my life with a crushing, consuming breakup. There never seemed to be a good time, either. Who wanted to be alone during the holidays, the Fourth of July, the first day of fall? I would give it six more months, I told myself. Maybe we could read more books. Maybe we could try a new therapist. Maybe we could go on a long vacation. It wasn’t all bad, I reminded myself.

Then that terrifying book came out. In the spring of 2002, Sylvia Ann Hewlett was detonating bombshells on nearly every talk show with Creating a Life: Professional Women and the Quest for Children. The message was clear: your fertility fades much sooner than you think; your eggs deteriorate dramatically after thirty-five and are pretty much fossils by your early forties. So listen up, all you clueless careerists! You’ve got to make having a family a priority. You’d better think twice about all your indulgent plans for advanced degrees, foreign postings, and after-work cocktails. Otherwise you’re going to break your heart and the bank pursuing futile in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments in an attempt to “snatch a child from the jaws of menopause.” That’s not to mention the increased risk of having a baby with Down syndrome if you manage to get pregnant.

I joined my generation in a collective gasp. “Now?” I whined to myself. I had just finished graduate school and was trying to launch my career as a freelance journalist. Plus, I still had to break up, grieve, find a new apartment, move out, lose ten pounds, acquire new relationship skills, and try to meet someone else. Then I had to get engaged, marry, and make a baby. That left very little contingency for rebounds, bad judgment, and trouble becoming pregnant.

If everything went as planned, I could have my first baby at thirty-seven and maybe fit in a second by thirty-nine. “My God!” I exclaimed to my girlfriend over the phone. “I’ve already lost my third child!”

Before Hewlett’s book, I had assumed that I would be a mother, just as I knew I would marry, buy a home, and at some point fit into those Oshkosh B’Gosh short overalls I bought two seizes too small in college. I sleepily went about my life and took comfort in the pleasant stupor that was someday. I had little sense there was an actual deadline and that it was looming. Life was challenging enough without God suddenly setting a timer.

Without knowing it, I had become a Clock Ticker, and my pleasant stupor was replaced by the loud hum of the clichéd biological clock, which began to torment me like a clunky old air conditioner. My friends started having babies, and I was suddenly behind. I overheard my parents making excuses for me to their friends: She’s busy with her job. She’s a late bloomer. She’s picky. In the most discouraging sign, relatives stopped asking me when I planned to get married and start a family, as if I had been relegated to being the Crazy Aunt at family gatherings.

There were statistics to prove you were not alone, and that you were a member of a swelling demographic of women who had delayed marriage and motherhood. Supposedly one in five women was waiting to start her family until after age thirty-five, a percentage that had increased nearly eight-fold since 1970. And for the first time in history, more children were born to women over thirty-five than to teenagers.

You saw enough older new mothers in your neighborhood to know the statistic was true, but secretly you still wondered if there was something wrong with you because life hadn’t worked out for you the way it had for Everyone Else. You told yourself that there was nothing wrong with being the Last One Left. You were simply on a different path and would make good decision for your future. But you still felt a little twinge of sadness every time you saw your single-line listing on a family reunion attendance list. Or shopped for boxed Christmas cards of New York City snow scenes because it seemed ridiculous to write a holiday letter about yourself. Or realized that you were one of a few friends from high school holiday get-togethers available to go out after 8 p.m.

I wish I could say that I trusted everything would work out and that I carried myself with a Secret-like confidence that made me wildly attractive. I didn’t. I spent the majority of my thirties alternately freaking out and talking myself down. I paid thousands of dollars for therapy, drank too much wine, and harassed my busy friends and family with distraught phone calls. I often repeated their encouraging words in my head before I went to sleep: I still have time. There are lots of good guys out there. I am in a better place now to choose a mate than I was in my twenties. I have learned a lot of relationship lessons. I still have time. But only one thing gave me real comfort. If I actually did run out of time, I had a list of motherhood options taped to my desk lamp: donor eggs, foreign and domestic adoption, other couples’ leftover IVF embryos, stepchildren. I knew the alternatives came with their own complications, but I thought they were ones I could live with. And if I had to live with them in the same house as my fabulous new husband, all the better.

So why did I still feel so awful?