Developer Bruce Ratner said Tuesday morning what many of his critics and even some of his associates have been saying for years: there is no way the entire Atlantic Yards project will be done in 10 years.

He said the 10-year timeline was always misunderstood. It was never meant to be more than a best-case scenario to be used in environmental impact statements.

“That was really only an analysis as to what the most serious impacts [would be], if all the other planned development in downtown Brooklyn happened right away,” Ratner said. “It was never supposed to be the time we were supposed to build them in.”

He added: “I would say it's really market-dependent as to when it will really be completed.”

But the 10-year-timeline was also used by the city, state and Ratner’s own consultant to determine that the financial benefits to the public outweighed the roughly $300 million in direct subsidies the project is receiving. But the longer the construction schedule, the longer it will take the government to accumulate the benefits—in terms of income taxes from people who move into the complex, property taxes on the new buildings and other sources.

Daniel Goldstein, a chief opponent of the project who until recently lived in the project’s footprint said that Ratner’s admission undermines the official reason for state support of the project: to remove the blight on the six Brooklyn blocks that make up the footprint.

“What we have now is a site that was not blighted turning into a dormant site, nearly 20 acres of vacant lots and parking lots for 20, 25, 30, 40 50 years,” Goldstein said. “What was not blighted has become blighted for a very long time.”

Goldstein, who lived in a recently converted condominium in the project’s footprint, until being bought out, never believed the area was blighted in the first place.

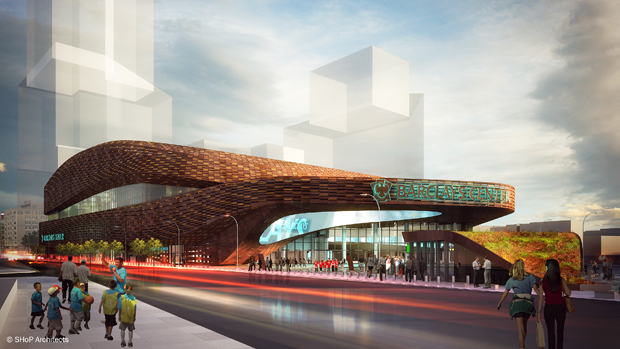

Latest design by SHoP Architects, PC of Barclays Center

The longer construction timetable also affects many of the assumptions the state and city made regarding whether the project is worthwhile for taxpayers to support, according to George Sweeting, deputy director of the city’s nonpartisan Independent Budget Office. That’s because the government is contributing about $300 million in subsidies in today’s dollars — but might not get that amount back for another 25 or 30 years, when that amount will be worth less.

“Those dollars — if you have to wait 15 years for them — are worth less in terms of today’s dollars,” Sweeting said.

The IBO, in conducting a cost-benefit analysis on Atlantic Yards last year, only considered the tax revenues from the basketball arena and ignored the impact of new residents and workers in the 16 other buildings because their construction dates were so uncertain. That analysis concluded that the arena would cost the city about $40 million more in subsidies than it would yield in new taxes. The IBO’s analysis was attacked by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Ratner’s company, Forest City Ratner.

By contrast, the city, state and Forest City all conducted or commissioned economic impact analyses that assumed a 10-year build out.

Ratner made his comments Tuesday morning after unveiling the design for the public plaza that will be constructed in front of the Barclays Center basketball arena, the centerpiece of the 22-acre site. Ratner said its construction was proceeding well, and the arena would open in the summer of 2012, in time for the Nets to play their 2012-13 season.

He also said that construction on the first residential tower—a mixed-income building—would likely begin in 8 to 10 months. But Ratner, the chief executive of Forest City Ratner, said the schedule for breaking ground on the remainder of the project—15 other buildings spread from Flatbush to Vanderbilt Avenues, just south of Atlantic Avenue—depending on when the economy rebounded.

One of Ratner’s top aides, Maryanne Gilmartin, said that Atlantic Yards was always supposed to be market-driven.

“We always said it would be market-dependent,” she said.

While the official agreement among Forest City, the state and the city, gives the developer 25 years to build out the entire site before penalties kick in, Ratner’s associates repeatedly used the 10-year time frame in talking to the press and the public.

In a July 2006 PowerPoint presentation to potential tenants of the affordable apartments held at the Marriott hotel in downtown Brooklyn, Forest City Ratner and its housing partner, the now-defunct Acorn organization, told participants that the “final building [would be complete] in 2016”—assuming a groundbreaking later that year.

Less than a year later, after the project got held up in court, Ratner’s then-project manager, Jim Stuckey, reiterated the 10-year timeline.

“We don’t believe it is going to take 20 years,” Stuckey told The New York Observer in February 2007. He was in charge of the project at the time. “We expect that it will take 10.”

He was responding to an assertion by the project’s landscape architect, Laurie Olin, that the build-out really would take much longer than publicized.

Last September, after Forest City rearranged its agreement with the state, a Forest City spokesman was again asked whether the construction schedule had been lengthened to 20 years.

“No, the plan is to build it in the ten-year time frame,” the spokesman, Joe DePlasco, said in an e-mail.