( Courtesy of WNET )

In a new podcast, After Broad and Market, journalist Jenna Flanagan revisits the 2003 murder of Sakia Gunn, a queer Black fifteen-year-old Newark Resident. Flanagan joins us to discuss.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. This week marks the 25th anniversary of the death of Matthew Shepard, a gay University of Wyoming student who died on October 12th, 1998 after being tortured and left tied to a fence. Earlier that year in Texas, a white supremacist tied James Byrd, a Black man, to a truck and dragged him to death. Both stories were covered widely in the national media, and their names are attached to federal hate crime legislation signed into law by President Obama in 2009, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crime Prevention Act. Shepard was white and gay, Byrd Black, and both crimes received a lot of attention.

That wasn't the case with a hate crime perpetrated against someone who was gay, Black, and a woman. A new podcast revisits the response to the 2003 murder of Sakia Young, a Black lesbian who lived in Newark. It is titled After Broad and Market, the intersection where she was knifed to death after rebuffing a man who came on to her. Now, nearly 3,000 high school students walked out of their schools to attend Sakia's funeral, but there was little media coverage of her murder. Now Newark is finally honoring Sakia with a street renaming near the LGBTQ Community Center. The ceremony takes place October 28th. Episodes of After Broad and Market are available wherever you get your podcasts.

In the [unintelligible 00:01:28] journalist Jenna Flanagan covered the story for WBGO. She is the host of MetroFocus and the creator and reporter of After Broad and Market, both presented by the WNET Group. She's also, of course, an alum of this time slot. She has filled in many times. Jenna, welcome back.

Jenna Flanagan: It's so great to be back. Thank you for having me.

Alison Stewart: You reported this story, the murder of 15-year-old Newark native, Sakia Gunn, while working at WNET. What do you remember about those early first days of the reports after her death?

Jenna Flanagan: Initially, right afterwards, I think there was a sense of shock, not just for her immediate community, speaking of Newark's queer community and also the high school kids, that she was very, very, by all accounts, wildly popular as a kid. I think for the larger city, there was shock at how much outrage and outpouring of grief there was. You mentioned that nearly 3,000 kids walked out of high schools to attend her funeral, but in the immediate aftermath, so many people showed up to the intersection of Broad and Market that it pretty much shut down one of the busiest intersections in the tri-state area.

Alison Stewart: What made you want to revisit the story on this anniversary?

Jenna Flanagan: When I first covered the story, and again, I have to admit, I was a very green, very new general assignment reporter for WBGO, NPR member station. Anyway, as you mentioned, this was just a few years after Matthew Shepard had died. I assumed that I was-- as heartbreaking as the murder was, and of course, any murder is, but I assumed that I was going to be witnessing another galvanizing moment of the larger, not only gay rights, but visibility movement. Above all that, this time, it was going to center a young, Black girl, and that there were so many other issues that that would bring to the table and that was finally something that there was going to be national attention and focus on.

To, frankly, my shock, that did not happen. For me, I think it was, I guess, best described as the deafening silence around her death that really just left me shook, and I've carried this story with me for the past 20 years.

Alison Stewart: Now that you are a seasoned journalist, 20 years later, what did you do this time around reporting this story that back then maybe in your gut you knew you wanted to, but maybe didn't either have the facility or the resources, and now you do have the opportunity to revisit the story?

Jenna Flanagan: Well, of course, as you said, being seasoned and having a better grasp on what it is that I'm doing. Above all, I would also say that in those subsequent two decades, my God, I remember watching as our understanding of the spectrum of gender, gender presentation, of sexuality, and our vocabulary and our language grew and developed where it's like intersectionality, the fact that we realized it wasn't just LGBTQ, it's LGBTQIA and plus, things like that. I had a better understanding of, okay, yes, you could say very easily on the surface. She was poor, she was Black, she was from Newark, she was gender-nonconforming.

She presented-- in the podcast, if you listen to it, you'll learn the term Ag or aggressive, which is how a lot of young, Black lesbians were describing themselves if they were very masculine presenting. I still knew that there was something a little bit deeper than that. I wanted to understand where some of the feelings of indifference or the ability to shake off her death while we collectively mourned others, where was that coming from? That was the stuff that I was able to really dig into with the help of academics and other journalists, and of course, her friends and family who have also had 20 years to reflect.

Alison Stewart: Also, we should say we get to know Sakia in your podcast. You really get to know her as a person, not just this person that a horrible thing happened to. What was she interested in when she was a teenager? What was she excited about?

Jenna Flanagan: Oh my God. Basketball.

Alison Stewart: Basketball?

Jenna Flanagan: She and her, officially, best friend, but the girls were so close, they were cousins, practically twins. Valencia Bailey, who you hear a lot from in this series, the two loved basketball, loved smoking other boys on the court in basketball. They played together all the time, and they actually had a dream of getting out of Newark and attending Yukon, where they would play for the Husky women's team.

Unfortunately, that never came to pass with Sakia's murder, but-- people described her as a funny kid. She was fun-loving. She had this almost magnetizing pull to her that people, if they were queer, even if they weren't queer or whatever, were just drawn to her. I think that's also part of what made her loss such a shock and also a gaping wound for so many of her classmates.

Alison Stewart: Let's listen to a little bit of the first episode of the podcast when we're introduced to Valencia Bailey, who you just mentioned. Here she is reminiscing on the first time she met Sakia in the 6th Grade. This is from the podcast.

Valencia Bailey: I remember maybe the fourth day, we were lining up outside our classrooms, and as I'm coming out, she was getting into her spot in line, and we looked at each other. It was like a twilight moment. Like-- [crosstalk] Like, wait a minute.

Jenna Flanagan: This is Valencia Bailey and her mother, Gayle [unintelligible 00:07:36] remembering the first day Valencia met Sakia Gunn in the 6th Grade.

Valencia Bailey: There's another one? I'm not the only one. There's someone like me. [unintelligible 00:07:45] We looked at each other and just looked at each other, and we did this, and it was like-- and towards each other with our fingers [unintelligible 00:07:55] That at was it.

Alison Stewart: That is from After Broad and Market, my guest is Jenna Flanagan. She is the producer and the host of the podcast. It's really interesting that she said another one like me, someone else like me. You get into this in the podcast in a really nuanced way, a little bit about respectability politics-

Jenna Flanagan: Oh, yes.

Alison Stewart: -and how that can drive who gets covered in the media and who gets our sympathy and why. Why did you want to go down that lane? How does it apply to Sakia?

Jenna Flanagan: It absolutely applies. Again, Sakia was gender-nonconforming. You could say, I don't know, tom boy. Again, Valencia was very clear that the word they used was aggressive. She wore the oversized t-shirts and the durags and the sneakers and all that other stuff. A lot of the kids actually said that when they first met her, they thought she was a boy. At the same time, still being very comfortable in her own body and identifying as a lesbian.

I wanted to go down that because one of the things that I struggled with when the story first happened was I could maybe not justify, but come to grips with, "Okay, so maybe a larger white media might not be as focused on this story, but here we have this murder of this young, Black girl who seemed to be very popular and have so much of her life ahead of her." Yet there wasn't that much, at least from what I could tell, from Black media. Actually, when we dug into the story, we found that, I believe something like 400 stories that Matthew Shepard's murder garnered. Sakia's only got like 60, and that's after months after her murder.

Respectability politics is I think something that especially the Black community, officially, we described it as a tactic used by marginalized communities when they're trying to gain power and acceptance by a dominant one. It's something that I think the Black community has struggled with in terms of where and when to use it and how that gets wielded, but what it ends up doing is it creates even a further gap between true liberation, if you will, and people, especially Black people who are in the LGBTQ community, because they aren't adhering to the traditional scripts of what a feminine woman should be or perhaps what a masculine man should be. Although we also do get into how toxic masculinity ends up trickling into everything and also played a role in Sakia's death.

Alison Stewart: In the second episode you reference a phrase by the late great Journalist Gwen Ifill. She talked about missing white woman syndrome, and she was very blunt about it, because Gwen would call it out, that was the greatest thing about Gwen. [laughs] That if it wasn't a missing white woman, the media didn't particularly care. This applies to Sakia in your opinion, yes?

Jenna Flanagan: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. Like I said, we went and we got the numbers to back that up, and her death simply did not get the level of attention or media articles or media stories that others did. This is not to say that nobody did cover it. There were some outlets, specifically queer media that did pay attention, and of course, local Jersey papers. We of course also did at WBGO, but then this happened in May of 2003, and as we all know later that summer, the East Coast went black and her story got completely wiped off the headlines.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Jenna Flanagan, she's the producer and the host of After Broad and Market. I wanted to revisit what actually happened to Sakia, because it's important too. She was hanging out with friends, two men approached her and it sounds like they cat called her, and she was like, "Not for me."

Jenna Flanagan: Yes. In fact, her exact words were, "We're not interested. We're lesbians." Which again, could have been a rally cry, but it just did not become one.

Alison Stewart: How did it escalate to the point of her not being able to walk away from that day?

Jenna Flanagan: First of all, it was about, I would say maybe about five girls or so. Sakia, Valencia, and three other girls I believe. They were hanging out at the Chelsea Piers, which a lot of kids were doing at the time. I think the queer presence of Chelsea Piers has been well documented. They were coming back home. It was wee in the early mornings, they are on the corner, Broad and Market waiting for the bus. This car pulls up and I guess what you would call two guys decide to holler at them, especially the more femme girls.

When I brought up the issue of toxic masculinity and how that plays out even in queer settings, is what we found from the story, is that as this man who was almost 10 years older than them attempts to hit on one of the girls, Sakia being more masculine presenting in the group, steps in between him and the girl that he's trying to holler at, if you will. It's like, "We're not interested. We're lesbians. Leave us alone."

In the podcast, again, I get into the details of how not just the rejection of his advances, but the rejection of his advances on top of, and we're not interested in any men, for some individuals can not just be emasculating, but can be enraging. I'm condensing it very quickly here, but basically a slight shoving match ensued and he ended up pulling out a knife and stabbing Sakia once in the heart and she literally bled out on the corner.

Alison Stewart: Yes. There's a really interesting discussion, and I can't remember which episode it is, is about that idea of entitlement. An entitlement of, "I'm talking to you as a man. You must respond to me."

Jenna Flanagan: Then there's also the issue that we got from, I want to say it was Dr. Angela Jones, who's a SUNY Farmingdale professor, who actually teaches this case in her class. Her point that she was making was that a lot of times people who are marginalized will sometimes look for someone even more marginalized to have dominance over, to have power over. One of the things that I believe was said in the podcast was that traditionally, masculinity has been defined by dominance.

Your ability to have that over someone else, so if you are already a marginalized man or identifying as a marginalized man, and then something happens to you where someone who you're supposed to have dominance over rejects you, it can become, I want to say, because this is certainly not everybody, but can become an enraging moment. What we also learned though, speaking of gender presentation, is that in the courtroom, the perpetrator claimed that he thought Sakia was a boy the whole time. Therefore he was just defending himself against someone-- even younger boy, I guess, who was attempting to attack him. Doesn't justify stabbing anyone in the heart, but that was something that came up several times in the court case, was that he thought Sakia was a boy.

Alison Stewart: What have local residents done to collectively remember Sakia?

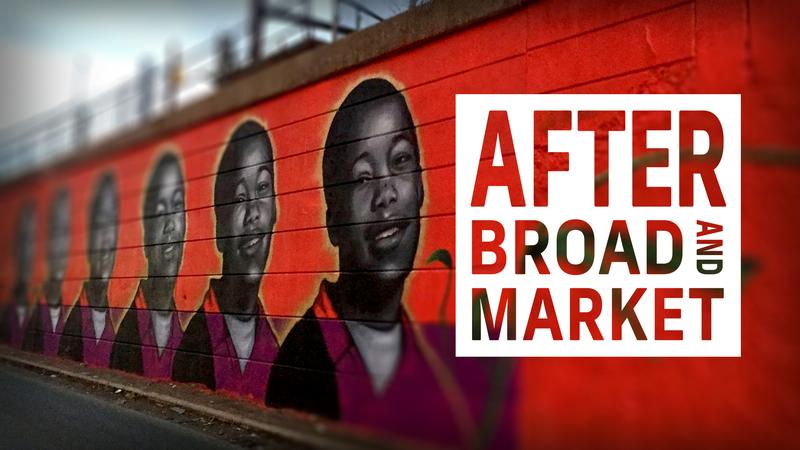

Jenna Flanagan: One of the things is, if you're at all familiar with Newark, if you're driving along McCarter Highway, you'll see that there is a series of murals and one of those murals is a long, red mural with a series of black and white images of Sakia that's actually I think taken from her 8th Grade graduation picture. We talk about the mural in the podcast and its significance, but for the most part, it was activists, people like Reverend Kevin Taylor with Project Wow which is a LGBTQ affirming space in Newark.

Also, Beatrice Simpkins, who is the director of the Newark LGBTQ Pride Center. They, along with family members and friends, have been working for years, because up until very recently, until the street naming takes place, the only two indicators that you would know that Sakia ever was in Newark is the mural along McCarter Highway and unfortunately her headstone.

Alison Stewart: Definitely check out the excellent podcast, After Broad and Market. I've been speaking with its producer and its host, Jenna Flanagan. Jenna, thank you for your time today.

Jenna Flanagan: Absolutely.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.