Staten Island is getting a second chance.

Fifty years ago, after a pair of hurricanes slammed New York’s coast, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers came up with a plan to protect the neighborhoods along Staten Island’s shore with a giant levee that stretched about four miles along the beach. But the plan foundered because New York City, suffering from its fiscal crisis, didn’t have enough money to cover its share of the cost.

Fast forward to Oct. 29, 2012: a storm surge 16 feet high pushes millions of gallons of saltwater up past the beaches, knocks homes off their foundations and kills 23 people – more casualties than any other borough of New York City experienced.

Now, the Army Corps has unveiled a plan for another levee. This time it’s taller, stronger and prettier. (It will feature vegetated slopes and a boardwalk on top.) And it looks like it is largely funded: nearly two-thirds of the $579 million price tag will come from the federal Sandy Aid bill passed by Congress in January 2013, and New York City has already set aside its portion: $60 million. New York state is also being asked to contribute $140 million. A spokesman for the Department of Environmental Conservation, Tom Mailey, said the state had siogned off on the plan but did not specify whether it would would contribute financially.

The Army Corps is holding public information sessions on its plan on Wed., Aug. 19, and Thurs., Aug. 20, at 777 Seaview Ave. on Staten Island. The program begins at 6 p.m. both evenings.

“We think this is an incredibly important project for residents on the East Shore of Staten Island, something they’ve been waiting for for a long time,” said Dan Zarrilli, the director of the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency. “We are fully supportive of making this investment.”

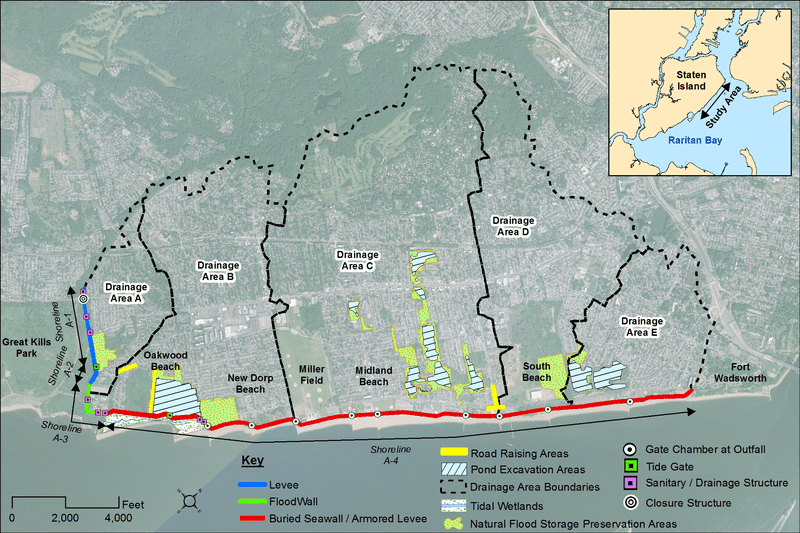

That said, some researchers are concerned that the levee – a reinforced ridge that will run from the Verrazano Bridge south four miles to Oakwood Beach – won’t be tall enough. As proposed, it will stand about 20 feet above sea level, and 10-12 feet above the ground on which it is placed. The Army Corps judges that to be sufficiently high to withstand a 1-in-300 year storm over the next 50 years – that is, a storm that is calculated to have a 0.3 percent chance of occurring in any given year.

But the Army Corps, because of its own rules, used a low-end estimate of sea level rise. Philip Orton, a research assistant professor at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, calculated the risk using a mid-point estimate endorsed by the New York City Panel on Climate Change. He determined that there was a 4 percent chance of a storm strong enough to flood the neighborhoods behind it over the course of 50 years – and said the impact would be much more catastrophic if it did happen. (That’s because once the Atlantic Ocean rose to the top of the levee, millions of gallons of water would come rushing over all at once, at a depth far higher than people could stand.)

The Army Corps plan calls for adding extra feet on top of the levee if sea level rise is more severe than it anticipates. But Orton, an oceanographer, said it would be better to build higher now, while attention, and money, is available.

“I think in 50 years, money’s going to be more scarce for coastal protection, because sea level rise will be badly inundating places like Florida, and there will be a fight over dwindling dollars,” Orton said. “So if they are going to build it, they should built it big, and try to tap into whatever money they can, and plan for 100 years or 200 years.”

There is one added bonus of the proposed levee: it will aim to relieve about 9,100 homes from having to get flood insurance, according to the city’s estimates. That is because the Federal Emergency Management Agency exempts low-lying areas from its flood maps if they are protected by certified levees.

(Zarrilli — and FEMA — both say getting flood insurance anyway is a good idea.)

Flood insurance rates are due to increase substantially and affect more people over the coming years.

The levee still needs to go through an environmental review process and receive final approvals before it is constructed.