NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

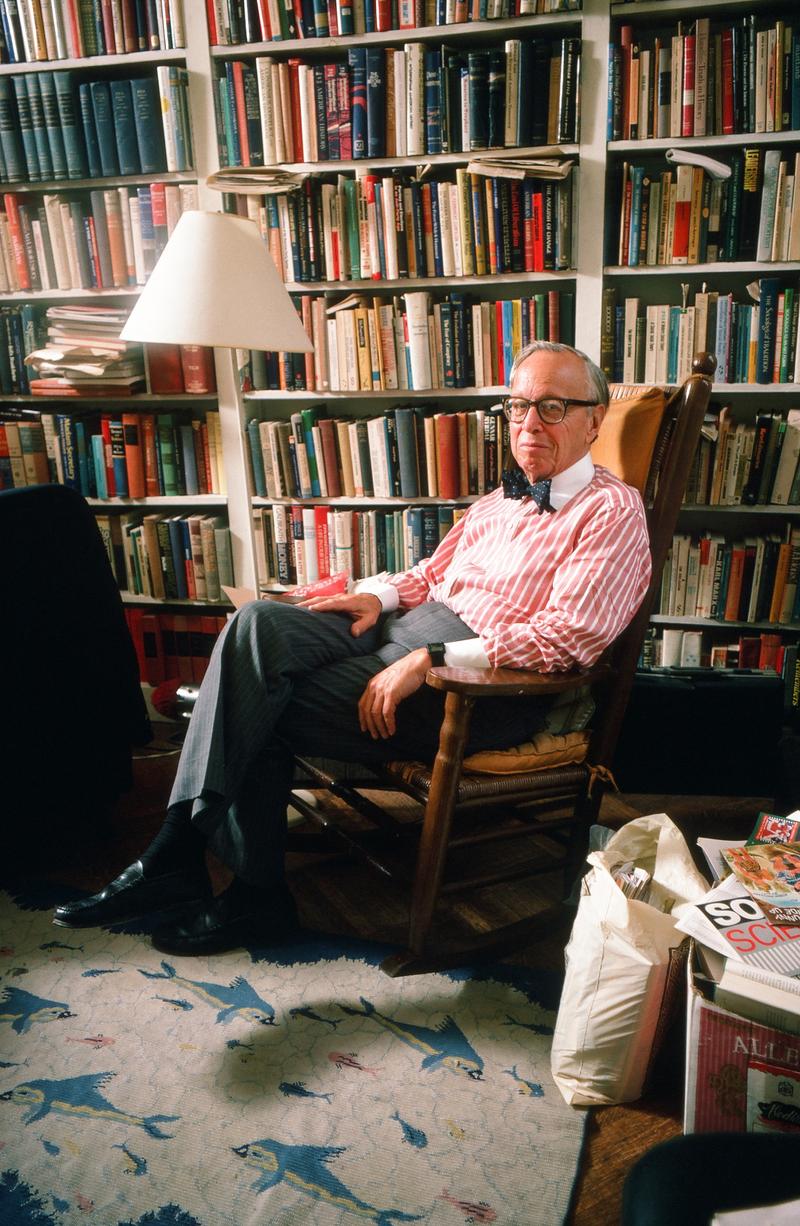

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.: Has the Constitution Outlived Its Usefulness?

It was a momentous time in our country’s history when the Pulitzer Prize-winning American historian, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. delivered a talk about the United States Constitution at the New York Public Library on October 6, 1987. Not only was it the year in which the nation celebrated the 200th anniversary of the Constitution’s existence, but it was also a period when Ronald Reagan's presidency was testing the integrity of the cherished document. The ongoing revelations of the Iran-Contra affair were the back drop for Schlesinger’s remarks.

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. was the former speechwriter for Adlai Stevenson who left a professorship at Harvard in 1961 to become an adviser to President John F. Kennedy. Schlesinger found a teachable moment in the Reagan Administration’s scheme to covertly trade weapons with Iran in return for the release of American hostages and to fund the Contras, the anti-Socialist rebels in Nicaragua. He noted that the clandestine presidential provision of aid to the Contras violated a law recently enacted by Congress and proved wrong those who claimed the Executive Branch had grown too weak. Furthermore, Schlesinger saw the scandal as a stark reminder of the wisdom of the Constitution’s Framers, who understood the fundamental importance of separation of powers between three co-equal branches of our national government. The Congressional inquiries and the Federal Court trials that shed light and imposed punishment on Contra-gate operatives served to block, albeit imperfectly, Executive overreach.

Schlesinger says the Framers wanted a strong central government but also knew that checks and balances were needed to preclude any president from becoming too strong. Alexander Hamilton, for instance, forcefully argued against granting a president arbitrary power to rush into conflict with other nations. Congress, vested with the exclusive power to establish armed forces and make war, was meant to have equal power with the president in guiding foreign policy. What this means, according to Schlesinger, is that decisions about war and peace are not to be made hastily; they must be made within the framework of discussion and deliberations between the president and Congress.

“It is a delusion to think that on matters of foreign policy the president is better informed than Congress,” Schlesinger asserts. He has firsthand knowledge of the type of blunders a president can make when deciding foreign policy from within a bubble: Schlesinger attended the 1961 meetings JFK held with the Armed Forces Joint Chiefs as they planned the infamous, covert Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. To his profound regret, the historian did not raise objections at these meetings, which led to one of America’s greatest military and foreign policy fiascoes.

Schlesinger does see uses for covert action. (Indeed, as an analyst just after World War II for the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor of the Central Intelligence Agency, he worked closely with America’s first Spymaster, William Casey). But he emphasizes that “there should be a presumption against Executive secrecy”: Schlesinger believes a president who operates in secret subverts our Constitution -- the oldest in the world -- by creating an imperial Executive Branch. His acclaimed book, The Imperial Presidency, analyzes the furtive methods President Richard Nixon relied upon to abuse power and undercut the Constitution. Unfortunately, the tactics developed by the Nixon Administration formed a template for the Reagan Administration.

The author of numerous books about American Liberalism in the 20th Century as embodied in the administrations of Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman and JFK, Schlesinger says that truly effective presidents know what needs to be done and are able to make their case to Congress and, thus, the American people. In his view, Reagan and his advisers decided that their landslide second term victory entitled them to act in secrecy. The Administration came to believe that it was “the savior of the world.” Quoting JFK, Schlesinger notes a wise president must understand that “we are not omnipresent or omnipotent [and there] . . . cannot be an American solution to every world problem.”

While Schlesinger states “the Constitution can’t guarantee against presidential incompetency or stupidity,” this unabashed liberal believes Americans should be proud of how the checks and balances built into our much admired system of government blocked further secret excesses by Reagan. “What better way to celebrate the Constitution’s Bicentennial?”