Just across from the FDR Drive, one of the first visible hurricane protections built since Sandy is going up: The Veterans Administration is building an 11-foot-high flood wall around the perimeter of its giant Manhattan hospital.

Meanwhile, the city's flagship public hospital, Bellevue, is just a block to the north. Construction on a similar flood wall there is not expected until the middle of next year at the earliest.

Both facilities were severely damaged in Sandy. But the rebuilding processes at the two facilities were funded through different paths. The city's took a lot longer, prompting a city lawyer to go so far as to consider mocking up letterhead of a federal agency, and leading the mayor to announce a deal five months before the details were finalized.

The Veterans Administration worked up its cost estimate just weeks after the October 2012 storm hit, according to the hospital's director, Martina Parauda. Being a federal entity, the VA took the estimate directly to Congress, which worked it into the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act, passed in January 2013.

"We worked with our headquarters in Washington D.C., and they sent up teams that were expert engineers, people from construction and facilities," she said.

But the city’s hospitals, like other city and state agencies and non-profits, had to go through the Federal Emergency Management Agency instead. Fairly quickly after the storm, the hospitals made basic repairs and resumed normal service levels. But about a year ago, city officials were growing frustrated with the lack of progress on new flood protection measures. There wasn’t even a final agreement over how much money the city would get.

Flurry of Emails

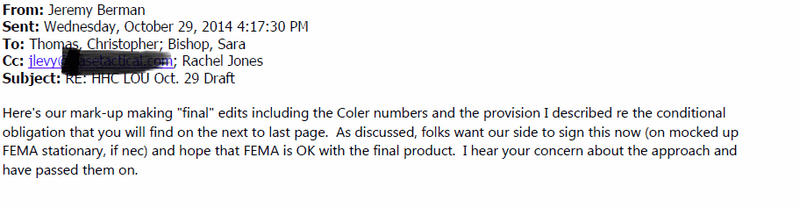

Emails obtained by WNYC through a Freedom of Information request show a flurry of activity on October 29, 2014 — the second anniversary of Sandy. The deputy general counsel of the city's Health and Hospitals Corporation, Jeremy Berman, proposed putting the city's version of the funding agreement on FEMA letterhead even though it wasn’t final, and having the head of the hospital system sign it.

It was unclear what would happen to the signed agreement. "We could send it to State by Fed Ex or PDF and/or we could send it to you," Berman said in a later email. Two FEMA officials described the idea as an attempt to somehow derail a potentially critical news story that a television station, NBC 4 New York, was working on, about how much longer it was taking the city hospitals to get aid compared to the privately-owned NYU Langone Medical Center.

"I wanted to keep you gentlemen in the loop on what the Dr. means to do to head off the press story," wrote Laura Phillips, the head of FEMA's Sandy Recovery Office, to counterparts in the city Office of Management and Budget and the state.

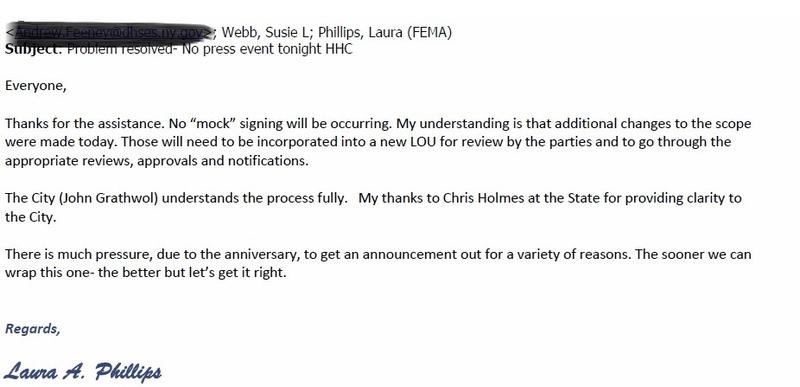

That email went off at 5:32 p.m. About 45 minutes later, the NBC story ran, noting that the city was expecting a $1.6 billion FEMA award, although there was no signed agreement. But later that evening, Phillips, the FEMA administrator, wrote that the city's plan was dead:

But Mark Treyger, the chairman of the City Council’s committee on recovery and resiliency, said the emails about getting an agreement signed before it was final raise questions about priorities.

"There should not be a sense of urgeny to give a reporter something for a story," he said. "There should be a sense of urgency to help people to recover from the worst storm that ever hit the city."

Earlier this month, Berman told NBC 4 New York that the idea of signing the agreement before it was final was not a public relations move.

"We were saying, 'Look, we'll start the document. We'll sign it and send it to you,'" Berman said, according to a transcript of the interview. He added that he and others had been working hard to get the money as fast as possible.

Berman referred questions from WNYC to the hospital system's press office, which said in a statement that "mocking up" an agreement letter was "a way to hurry the process but that idea was rejected."

A FEMA spokesman, Don Caetano, said: "I can't speak to what folks thought or didn't think. I can tell you there was no mock [agreement] and say that our folks were clear in advising against a mock [agreement.]"

A Mayoral Announcement

On Nov. 6, 2014 — eight days after that flurry of emails — Mayor Bill de Blasio held a news conference in which he announced that FEMA would give the city at least $1.6 billion for its hospital system, both to make repairs and make the facilities more resilient. The mayor characterized the agreement as a "commitment" rather than a done deal; officials for the city said a final agreement would be signed within a week. FEMA representatives did not attend but they confirmed to WNYC at the time that a deal was forthcoming.

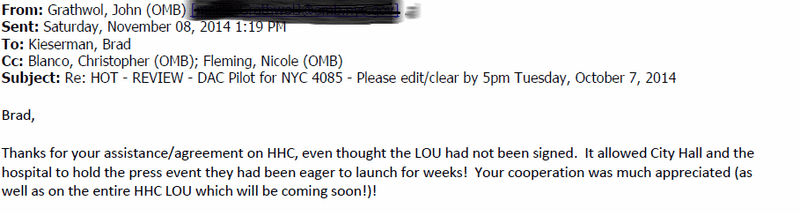

Two days later, Grathwol, the city's deputy budget director, thanked a top FEMA official, Brad Kieserman:

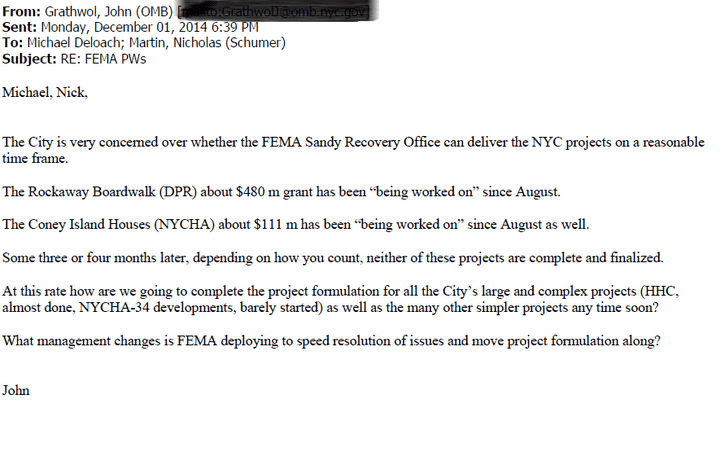

But no agreement was signed within a week. In fact, it took much longer. Both sides found problems with the details. In December, Sen. Chuck Schumer got involved. Grathwol gave a Schumer aide talking points that New York's senior senator could use in an upcoming meeting with the head of FEMA, Craig Fugate. Grathwol was far from cordial about an agency he had previously praised. (He referred all questions to the press office.)

However, Dr. Ram Raju, the head of the city hospital system, didn't sign the agreement until April, five months after the Sandy anniversary. The final agreement actually increased the amount FEMA would give to the city above what de Blasio had announced the previous fall, to $1.72 billion. A spokesman, Ian Michaels, said about $110 million addiitonal money has since been added.

The de Blasio administration wouldn’t make Raju available for an interview. But in a statement from his press office, he said city hospitals had implemented some resiliency measures and that design on the flood walls had already begun or would begin shortly.

According to officials from both sides, some of the delays had to do with a new pilot program that FEMA was trying out after Sandy. Previously, FEMA applicants were given a preliminary award and then would go back to FEMA to ask for more money if they encountered obstacles. The pilot program caps the award any applicant received at the outset, requiring the Health and Hospitals Corporation to fully scope out what it wanted to undertake and what difficulties it might encounter.

"Since this is the first time it has ever been used, it takes time to get it right," said Brad Gair, a former city official who directed the city's Housing Recovery Office under Mayor Bloomberg.

Gair, who is now vice president for emergency management and enterprise resiliency at NYU Langone Medical Center, said the city may well end up with more benefits in the long run as a result of the new funding system. As for the plan to mock up stationery, Gair wouldn't make a judgment.

"Every organization has its own external communications processes in place," Gair said.

This story was done in partnership with NBC 4 New York.