The Brian Lehrer Show

The Brian Lehrer Show

Bestselling Author Jodi Picoult Warns Against Book Bans

( Ted Shaffrey / AP Photo )

In a recent op-ed for the Daily Beast, bestselling author Jodi Picoult condemned the removal of several books, including 20 of her own, from a school district in Florida. Many of these challenges were filed by a single person. Jodi Picoult and Suzanne Nossel, PEN America chief executive officer, explain what's at stake as states and local governments continue to ban books.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Now we have the author, Jodi Picoult, joining us along with Suzanne Nossel, the CEO of PEN America, the free speech organization. Many of you know Jodi Picoult. She's written bestsellers like My Sister's Keeper and Nineteen Minutes, and so many other books. More than 20 books. Normally when novelists join us, they're hosting or they're being part of a discussion here about their latest work, but Jodi is not with us for that purpose today.

Instead, she's shedding light on the banning of her books in Florida, many of them, and, to the larger point, why many children throughout the country, but particularly in Florida currently do not have access to a large number of books, even in libraries, including her own at their schools. According to PEN America, a total of 175 books have been removed from bookshelves just in Florida schools.

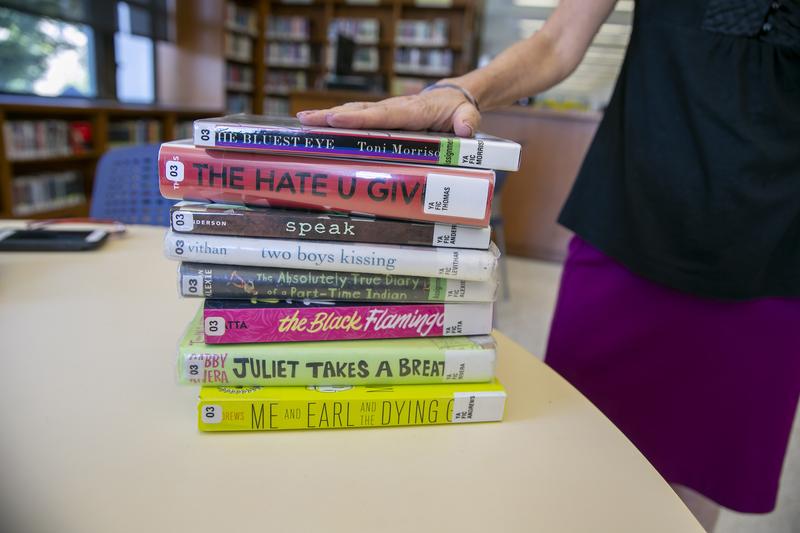

Some of the books on the chopping block include Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye, The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood, and dozens of others that touch on race, LGBTQ themes of any kind, or contain protagonists of color. With us now with her personal story and her reflections on why so many books are being banned from Florida schools and the significance of book banning is the author Jodi Picoult and Suzanne Nossel, PEN America CEO. Suzanne, welcome back. Jodi, welcome to WNYC.

Jodi Picoult: Thank you.

Suzanne Nossel: Thanks, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Jodi, what's on the chopping block with respect to your own books? Where do you even start? I see there are a lot of them.

Jodi Picoult: In Martin County, Florida, 20 of my books were removed at the request of a single parent. It's worth noting that she has admitted she hasn't read the books nor does she have to to have them removed and she doesn't even really have to give a reason for having them removed, although in some of her filings, she said they were adult romance. That was really interesting to me because I don't write adult romance and more than half of the books that she cited do not even have a single kiss in them. What I do tend to write about though are topics like gay rights and racism and women's reproductive health and gun control and topics that encourage teens to think for themselves.

All I know is that a lot of my books are off shelves in the school district in Florida with no good reason. It's, to me, really shocking and upsetting. The book that surprised me the most was a book called The Storyteller, which is about the rise of fascism in Nazi Germany. To be honest, having that one pulled off a high school bookshelf felt almost too ironic to be true.

Brian Lehrer: Is that your book that tells the story of the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor?

Jodi Picoult: Yes, it is.

Brian Lehrer: You want to talk about that book a little bit? Just describe the book in some detail for our listeners so they can get a sense of the degree to which book-banning is taking place?

Jodi Picoult: Of course. As you said, it's the story of the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor. It's really about the nature of good and evil and whether or not if you've done something terrible in your past, you can atone for it, and what, if you consider yourself a good person, could make you do something that the rest of us might consider evil. When I was thinking about writing that book and I was thinking about good and evil, my head immediately went towards the Holocaust, which to me seemed to be a great marker of evil in history.

The book follows not just this granddaughter in the present day, but also flashbacks of what happened during the actual Holocaust to her grandmother and to a gentleman that this granddaughter meets in the present day who has ties to Nazi Germany. It is about history and it is about telling the stories of many people who are no longer here to tell those stories themselves. That's part of the job of, at least in my mind, fiction. I did do a great deal of research for that book, including speaking to multiple Holocaust survivors and historians, and braided a lot of their stories together to create the one of my fictional character.

It's a very important book especially nowadays where we have fewer and fewer survivors of the Holocaust that are still alive. We need those stories on shelves so that kids can remember this happened and most importantly so that we can keep it from happening again. Which, again, brings me to the irony of book bans, of one parent deciding that a book is not right for her child, so, therefore, it cannot be right for anyone else's child. That sense that one person's opinion or that there's one way to think is the only way to be is right out of a fascist playbook.

Brian Lehrer: Well, about that book in particular I'm curious why you think it really got banned because certainly keeping the memory of the Holocaust alive would be something that I think would be politically correct according to Ron DeSantis, politically acceptable according to Ron DeSantis. Why do you think that particular book really got banned?

Jodi Picoult: Is it? Is that really okay according to Ron DeSantis? We also know that there have been challenges to curriculum in Florida saying that parts of actual American history, like our history with enslavement, for example, makes certain kids feel badly because they're white. That sense that you can eviscerate parts of a curriculum, that you can surgically exclude pieces of history as if they never happened just so that a child today doesn't feel guilty in some way does not seem to me particularly healthy or a reflection of actual history.

Brian Lehrer: I guess I just thought the politics would be more sympathetic toward keeping the history of the Holocaust alive than exploring more details of slavery.

Jodi Picoult: Who's to say? We've certainly seen a rise in anti-Semitism in this country, so I would not be surprised if that is what in particular led to that particular novel being pulled off a shelf.

Brian Lehrer: Suzanne Nossel, I will just remind the listeners that you have a long history of coming on the show accompanying people with all kinds of denials of free speech [chuckles] in your role as CEO of the free speech organization that has done so much to represent many authors, in particular PEN America. What do you think is going on with Jodi Picoult in Florida?

Suzanne Nossel: Look, it's not just Jodi. There are scores of authors who've seen their books banned over the last year and a half here in the United States. I'm used to being on the show often with authors from around the world who've been persecuted or banned or punished for what they write. It's not something we've been accustomed to at anywhere near this level here in the United States, but it has become a tactic of choice and this culture war that is being waged clearly.

The governor of Florida, and he's not alone, we're seeing this across the country, believes that there is political gain to be derived by empowering lone parents to wage war on their school's libraries and classrooms to take away kids' freedom to read. I think we can all remember the power of discovering something like Jodi's book when we were a child and opening up a window into a period in history that we don't know about, awakening feelings about ourselves, identifying with a character. This is being systematically shut down on a whim, empowering individual parents.

My guess about that book is it may have just been put on a list because there were other things that Jodi had written that they didn't like, so why not just add this? We know that the person who did the objecting, she admitted she hadn't read the books. It is a frightening situation where we have turned over the power of our children's education to these citizen vigilantes who are going after books, who are suppressing ideas. It's a sad moment to be on your show to talk about this happening right here in our own country.

Brian Lehrer: DeSantis claims that book banning in Florida is a hoax. He's used that word and that only pornographic and inappropriate titles, those are his words, pornographic and inappropriate, have been stripped from the shelves. Suzanne, what are you seeing?

Suzanne Nossel: I actually, in a weird way, was slightly heartened when he came out to do a press conference about two weeks ago to say that this was hoax because I think what it signifies is he's realizing perhaps that book banning can be a liability in some quarters, that being thought of and regarded as a book banner may not be such a political winner. Now the facts are he pointed to about three or four books that are edgy. They deal with LQBTQ topics. They're probably honestly more appropriate for high school than let's say middle school, but that is nowhere near the--

First of all, those books shouldn't be banned and secondly, that's nowhere near the scope of what's happening in Florida. Jodi's books, to call them pornographic makes a mockery of any definition of that term. We have a legal definition of that term. [chuckles] As Potter Stewart said, we know it when we see it, but the law's gone beyond that. We deal with pornography, we have ways of regulating it in this country.

The books that we're talking about, Toni Morrison's books, Jodi Picoult's books, James Patterson's books, children's books about penguins and about babies of different races and ethnicities, they call these pornographic is just insanity. Biographies of famous sports figures like Hank Aaron. Now he will say in some instances, those books were withdrawn temporarily, but temporarily can mean 18 months in some instances while there are these investigations that are ongoing, again, triggered often by a single complaint, and the books are whisked away. A kid may be out of middle school by the time it gets back on the shelves for their purposes. It's just missing completely.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, I wonder if anybody out there right now is dealing with a book banning yourself, either as an author or as a parent trying to get a book banned or trying to stop a book from being banned in your child's school library or anything related. Anybody with personal experience in this area right now? Any librarians listening right now who feel in the cross hairs or have experienced anything directly at your library school or general public library? 212-433WNYC, 2112-433-9692. Sure, if you want to be a fanboy or a fan girl for Jodi Picoult for a minute, you can do that too. 2112-433-9692 or a tweet @BrianLehrer for Jodi Picoult and Suzanne Nossel.

Suzanne, can you talk a bit about the process for getting books banned in a school district in Florida? Jodi's talking about Martin County there in particular. I'm not sure where in Florida that is myself, but 20 books of hers banned that she says were banned at the request of just one parent. How does the district decide what books should not be available for students in their schools?

Suzanne Nossel: Sure. There's some variation by district, but what we're seeing in the most troubling pattern is essentially an objection is lodged by a single individual, doesn't even have to be a parent. It could be a citizen who doesn't have kids in the school. In some counties, that objection is enough to get the book pulled from the shelves of every school library and classroom library in the entire county.

That could be many dozens of schools. In many of these counties, they then have some kind of review process where they will assemble a committee to look at the book, but they seem to do that at a very measured pace. Again, it can be many, many months. In some counties, librarians and teachers are being instructed that until a book is reviewed, it cannot be put on the shelf.

That is why we see these photographs of empty shelves in libraries in those schools where out of an abundance of caution and really fear, outright intimidation, the teachers and librarians are being told to essentially box up the books until a media specialist reviews every single one and gives it a green light. That reminds me of pre-publication censorship in the authoritarian regimes around the world that a special committee has to approve a book before it can go on a shelf.

This is not the way we're used to doing things in the United States of America. You can imagine that for teachers and librarians whose life's work is to introduce children to literature, to get them excited about reading, that it is just chilling to suddenly be under these constraints, to not be able to guide kids to books and help foster a love and a fascination with novels and fiction. We've heard from kids who feel like their own rights are being infringed upon and they can't understand.

Their parents always wanted them to read, their teachers were encouraging them to read. This is something they're supposed to be doing instead of spending time on their phones and on television, and yet all of a sudden now they're reading is interrupted. The books that they're curious about are being whisked away. They're not allowed to make their own choices. It's incredibly disempowering for a generation that we're trying to raise to be democratic citizens in a pluralistic society where they need to be exposed to all of this.

Brian Lehrer: I just looked up Martin County. It's in southeast Florida. It's north of the Miami area, north of the Palm Beach area. It's around Port St. Lucie, includes Port St. Lucie. The New York Mets couldn't read Jodi Picoult's books if they went to the school library because as some New Yorkers know, that's where the Mets do spring training. All right, how about Alan in Palm Beach County, Florida. Alan, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Alan: Good morning. Thank you for taking my call. I do substitute teach down here and I did teach the Holocaust because it's a mandate and at the same time, we can't use The Diary of Anne Frank, we cannot use Mouse. The books are just banned. Just on the good side, when my fifth graders learned that these books were banned, they made the connection to the book burning in Berlin and said, "Isn't that what the governor is doing to us now?" That's the good part, if it all.

Brian Lehrer: You had a conversation about this with students in one of your classes?

Alan: No, I have to teach. We have a mandate to teach the Holocaust. During my time, I had to teach the Holocaust. It's a mandate to teach the Holocaust.

Brian Lehrer: You talked about the book banning as well, or no?

Alan: Well, what happened was we showed a video of the book banning and discussed why The Diary of Anne Frank was no longer appropriate and the students just on their own, said it sounds like what was happening in Germany is happening here. [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Alan, why according to the state, The Diary of Anne Frank, of all things?

Alan: They don't give a reason. They just send a list of what you're not allowed to use.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. Jodi, have more people gone out to get your books in bookstores because the ban is drawing attention to them and it's backfiring on the censors?

Alan: That's usually what people are told. I hear all the time, "Oh, it's great. Your book's banned. It's going to sell like hotcakes." It's worth saying that I have a long career, I have a long history, and that if I am seeing a bump in sales, first of all, that is not the way I would wish it to happen. Second of all, that the majority of people who are targeted by book bans are mostly LGBTQ authors and BIPOC authors who write at a middle-grade and a YA level.

For them, book bans actually do the opposite. They decrease the number of sales that they have because a lot of their sales are in school libraries. That's a fallacy too, that idea that a ban means a book is going to sell like crazy. I think it's good to at least identify that that is not always the way that it works, particularly for the groups that are being banned now the most.

Brian Lehrer: This is WNYC FM HD and AM New York, WNJT-FM 88.1 Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJU 89.3 Netcong, and WNJO 90.3 Toms River. We are New York and New Jersey Public Radio and live streaming at wnyc.org. A few more minutes with the author Jodi Picoult, who recently had 20 of her books banned in St. Martin County, Florida. We're talking about that in the larger context of the Florida and elsewhere book banning movement with Jodi and Suzanne Nossel, CEO of the pro-writer and pro-free speech organization, PEN America. Let's take another call. Here's Joe in Irvington, New Jersey. You're on WNYC, Joe. Hi.

Joe: Good morning. I would like to thank you, first of all, for all your service and excellent interviews.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you.

Joe: I would like to say that in concerning the book banning, there's a very good read by a Puritan in the mid-17th century whose name was John Milton, and wrote an excellent essay called Areopagitica about book banning and seeking truth and falsehood. No one seems to know about it or remember it, but it's very relevant and I wish it would come into the public forum and open to public discussion.

The other thing I would like to say is that someone should, and someone in Florida should request that the Old Testament be banned because it doesn't actually depict, but it implies the existence of incestuous relationship because Adam and Eve, they first attained an apple who then went on to populate the world. If there was no one else, then it had to be based on incestuous relationship even with their parents or with sisters.

Brian Lehrer: John, [crosstalk] thank you very much. That's one way to look at the Old Testament. Suzanne, do you want to take that on in any way? Certainly, we could look at lots of things in the Bible if we wanted to point out a lot of sexual relations in the Bible. The Bible condones slavery by regulating it rather than saying it should be abolished. All kinds of things.

Suzanne Nossel: Yes. Well, it's funny because we joked the very same thing that was on Joe's mind that one could very well say that the Bible is filled with pornography based on this loose definition that's being applied to books like Jodi's. In fact, in Utah, there now is a parent who has lodged an objection to the Bible and they have detailed chapter and verse of biblical passages that are sexually explicit, that depict sexual relations and the school board is having to deal with this as they would an objection to any other book.

I don't know who this parent is, the name hasn't been disclosed but I think this person, they get it and they're putting their finger right on it which is just the hypocrisy and the irony of it. I think the caller harking back to John Milton is absolutely right. These principles of free expression are so deeply embedded in our own constitution, in Western thought.

The idea that if there are books and ideas that seem challenging or even dangerous or worrisome, that the answer is more speech. It's explication, it's analysis. If you disagree with it, it's rebuttal. It's not suppression and muzzling and silencing of ideas. I think that's particularly important when it comes to the classroom which is a place where we want children to be imbued with a spirit of free inquiry. That's the heartbeat of our country. We have lost a sense of what these principles are. Those who are championing these bans are turning their backs on the First Amendment and on our traditions.

It's really important to see this for what it is. Hearing that The Diary of Anne Frank is banned for a reason that a teacher can't even articulate, can't explain to the kids why that is. I find that absolutely chilling. I don't even know if that's a documented ban. I have to check with my colleagues but I think they're casting a mode of fear where teachers and librarians don't even know what may get them into trouble and have become very cautious and wary. That is the environment in which our children are now being educated in certain parts of the country. I think it ought to worry all of us.

Brian Lehrer: We have time for one more call. Look at this, we're getting a call from Martin County, Florida. Here is Ronnie in Martin County. Ronnie, first of all, I want to apologize for not knowing where in Florida your county is because I have actually vacationed in Port St. Lucie so that I could swim in the ocean and see the Mets on the same day but there you go. Martin County. Hi, Ronnie, thank you for calling in.

Ronnie: I have to explain to you that Port St. Lucie is a different place than Martin County. Martin County is 175,000 people just north of Palm Beach County. Port St. Lucie, St. Lucie County is a completely different place, way larger than where I live. Absolutely, way larger. Two-thirds of the registered voters in Martin County are Republican. This is not an issue of book banning.

I am a New Yorker at heart. I love where I live because of the weather, it's the reason why I stay here. This is an issue of getting Ron DeSantis elected as President of the United States. He is pandering to his audience. You can't walk down the street and find a Democrat here. He knows this is a winning deal, fighting for book banning, so he makes people feel that they have a voice.

That's why Trump got elected. He made people feel they had a voice. Whether it was right or not, he made them feel they had a voice. It is tragic if this man gets elected. He is making board of education elections partisan. He endorses people because he wants who he wants on the board so he can get more press out of this. Honestly, he's like Rush Limbaugh. I don't believe that Rush Limbaugh ever believed in everything he said, but he knew what his shtick was. He got people to listen to him and Ron DeSantis is doing the same thing. His only objective is to be president. That's it. If he finds a winning issue, he's going to hang onto it.

Brian Lehrer: Ronnie, in your estimation, is there just so much hatred of LGBTQ people that he's hanging this primarily on that? That's not how he puts it but that's really what he's playing to.

Ronnie: Absolutely. He is playing to get votes. That is the only reason why he's doing some of the things that he comes up with. There's a bill in Florida legislature, which is going on right now which is going to say you cannot take down Confederate statues. If you follow what's going on in the Florida legislature, you will be way more scared of him than Trump to be president, and he has a super majority. Everything he wants, he gets. It's scary.

Brian Lehrer: LGBTQ people and Black people, we should say. In fact, Suzanne, I don't know if this is in your portfolio but we did a segment after DeSantis objected to the AP Black Studies curriculum for high schools. Then the AP board, the College Board seemed to water down the AP Black Studies curriculum in exactly the ways that DeSantis wanted but I still don't think he's accepted that curriculum for high schools in the state, do you know?

Suzanne Nossel: I don't believe they've made a decision on that. Absolutely, look, the College Board claimed that they were not acting in response to the objections that they'd gotten from the state of Florida but that is how censorship works. It's not necessarily that they consciously said, "Let's capitulate," but rather that when you have the force of government being used to muzzle and exclude certain ideas, it reshapes the way people think, the way the people on that committee construe their endeavor. They may not have consciously been acceding but they nonetheless, as you say, turned up with a curriculum that wiped out much of what had been in contention.

That's what's so scary about the normalization of these tactics. I agree with the caller this is a political tactic. It's being driven by ambitions for national office but it's also normalizing this whole set of tools and laws. Even the idea that there would be legislation dictating what can and can't be taught in schools, that's not the way we've done things in this country. We trust our educators. We trust our college presidents and professors to make these decisions but now you see this Florida legislator, sure and unfortunately, they're not the only ones around the country, meddling directly to dictate how these issues are handled, what can be on a college curriculum.

We've got to push back or else we're going to see these kinds of laws just becoming part and parcel of the playbook in our political tussle.

Brian Lehrer: Jodi Picoult, before you go, for raising these issues publicly and talking about your own experience with having 20 of your books banned in that Florida County, you at least get to do a little plug. Do you have any recent work that you want to highlight?

Jodi Picoult: Oh, absolutely. My most recent book is called Mad Honey. I think the only reason it hasn't been banned yet is because probably they haven't read it yet in Florida but it certainly would be on the list otherwise. What I really wanted also bring back this argument to is the idea that the losers here are the kids. These are a bunch of parents who are saying, "We want to protect our children."

They're not protecting their children. They are actually making the world more difficult and dangerous for them by not exposing them to other points of view, to compassion, to other kinds of people who may be different from whom they are. They are putting their own children at a disadvantage by doing this. I think it's important to recenter the argument around these kids because they are the ones who are losing.

Brian Lehrer: Jodi Picoult and Suzanne Nossel, thank you so much for coming on today.

Suzanne Nossel: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.