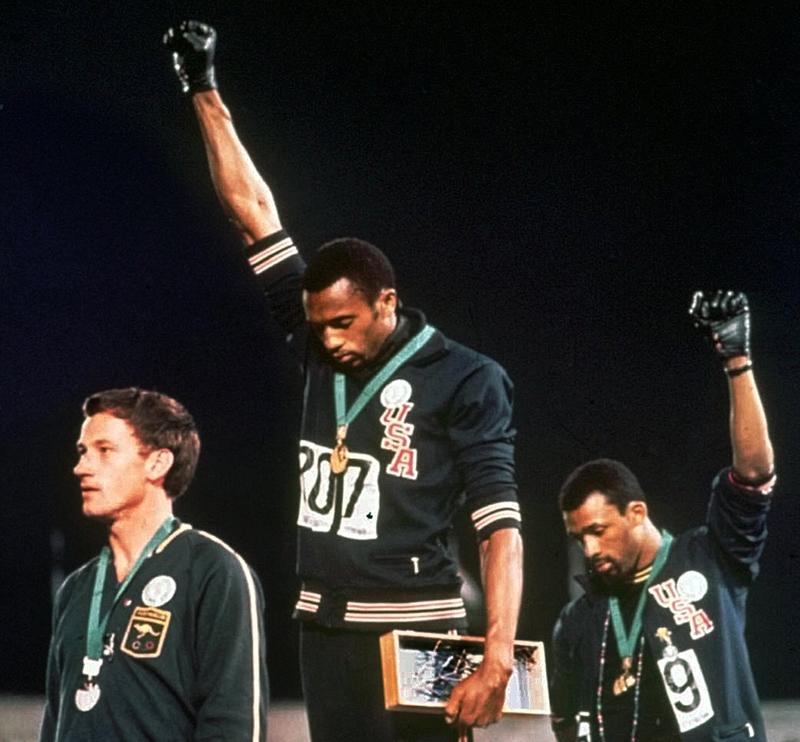

In the first of two segments looking back at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, we examine the iconic moment in which U.S. sprinters John Carlos and Tommie Smith hung their heads and raised their gloved fists after receiving their medals.

The iconic moment from the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, in which U.S. sprinters John Carlos and Tommie Smith hung their heads and raised their gloved fists after receiving their medals, wasn’t meant to be that way.

The idea that morphed into that image started almost a year earlier, shortly after a young, black sociologist named Harry Edwards arrived at San Jose State University as a visiting professor. Profoundly disturbed by the backlash against the civil rights movement, he co-founded an initiative, the Olympic Project for Human Rights, to leverage the high profile that African-Americans gained when they excelled at sports.

In November 1967, Edwards discussed the project at a Black Students Conference in Los Angeles and proposed that black athletes boycott the Mexico City Olympics that were to take place the following year. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. even made an appearance to show his support.

“Our churches were being bombed,” Edwards remembered in a recent interview with WNYC. “Our leaders were being shot down in broad open daylight. Black people were being beaten, driven down the street like basketballs with fire hoses that were so powerful they would take the bark off of trees."

He continued, “We thought that this went beyond trying to get a court judgement to halt this kind of behavior. We thought that it was necessary to bring this to the attention of the world.”

In the end, however, the boycott didn't happen. In his book, The Revolt of the Black Athlete, Edwards reflects that a universal boycott would have been impossible, too many people had too many opinions, and too much was at stake for these young athletes. Ultimately, the Olympic Project for Human Rights decided that each athlete would decide how to protest, and whether to attend the Olympics.

(Only one stayed home. That's Part 2 of our story.)

Sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos made the U.S. Olympic Team, and headed off to the Mexico City games, which were held in October, rather than the summer, because of the heat.

On Oct. 16, the fourth day of the games, Tommie Smith ran the 200-meter dash in 19.83 seconds, breaking the Olympic, and world, record. His American teammate, Harlem-born John Carlos, came in third. Then together, the two runners took off their shoes and carried them, walking in their socks, as they mounted the victory podium to protest poverty back in the United States. Smith wore beads to denounce lynching; Carlos wore a black scarf around his neck to show support for black pride. And while the, "Star-Spangled Banner," played over the loudspeaker, they bowed their heads and each held a fist in the air, covered with a black glove.

Howard Bryant, author of, The Heritage: Black Athletes, a Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism, explains, the gesture was not intended as a "Black Power Salute," but rather as a recognition of the human rights of all people. Quickly, however, the gesture began to resonate as more.

As American black athletes continued to win medals, similar signs of protest appeared. When the U.S. won gold in the 4 x 400-meter relay, three members of the team — Lee Evans, Larry James and Ron Freeman — all wore black berets to their medal ceremony and also thrust their fists in the air. When Queens native Bob Beamon cleared an astonishing 29 feet, 2½ inches, shattering the Olympic and world long jump record, he walked to the podium wearing only black socks, pulled high over his sweat pants.

The tradition of black athletes and other celebrities leveraging their notoriety into political statements goes back to actor and singer Paul Robeson, who played football in college and the NFL; it continued with baseball Hall-of-Famer Jackie Robinson and, of course, boxer Muhammad Ali, who went to prison for his beliefs. But with the 1968 Olympics, as all the world was watching, this tradition reached a clarion pitch, for which Smith and Carlos payed price.

Smith and Carlos were suspended by the U.S. Olympic Committee and expelled from the Olympics. When they returned home, they were treated like traitors. Their athletic careers unraveled. For years they received death threats. They couldn't find good jobs. Their marriages failed, their families suffered. Carlos blames the suicide of his first wife on the post-Olympic pressures they faced.

Theirs is still regarded as one of the most courageous political demonstrations in sports history, one that has inspired generations of activists through to the present day.

For more segments in our series, 1968: 50 Years Later, visit our series page.