When the courtroom doors open at 9:30 a.m. in Bronx housing court, hundreds of people are already waiting to enter. Tenants with children, landlords and lawyers for both sides are all jammed into a narrow hallway. In the middle of this cacophony, a young lawyer named Andrew Darcy approaches tenants individually.

"The city is offering free legal services to certain tenants so long as you’re eligible," he told skeptical looking men and women.

Darcy is a supervising attorney with the group Mobilization for Justice, which is among several legal service providers under contract with the city to provide free representation to tenants. The criteria include living in one of 10 ZIP codes (two per borough) and making less than $50,000 a year for a family of four.

The program started last spring and will go citywide over the next five years, now that Mayor Bill de Blasio signed the "right to counsel" legislation in August. New York is the first place in the nation to guarantee attorneys for low-income tenants in housing court. The U.S. Constitution's right to counsel is only guaranteed in criminal proceedings, not civil ones like in housing court.

In a city where rising rents are putting a squeeze on low income tenants, advocates see the right to counsel as a way to help keep people from being unfairly evicted. Jordan Dressler was appointed Civil Justice Coordinator after Mayor de Blasio took office. Historically, he said landlords almost always had lawyers, but tenants rarely had them until the city invested in more legal services.

"When we came in, in 2013, legal representation for tenants facing eviction in court was at roughly 1 percent," he recalled. "As of last year it was at 27 percent. So more people are getting access to counsel."

The law will cost $155 million annually by the time it's in full effect. A look at how it's working in the Bronx reveals several challenges, notably the lack of space for attorneys and clients to meet in private without being overheard by landlords or their attorneys. Only a few conference rooms are available. The vast majority of people meet outside the court rooms in a narrow hallway about 10-feet wide.

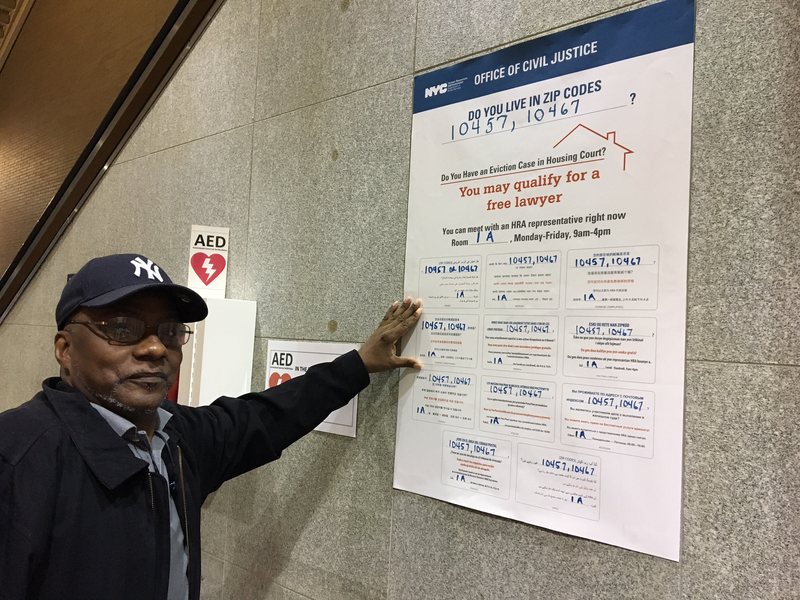

With the exception of a poster in the downstairs lobby, there are no signs showing tenants where to go, or notifying them which ZIP codes qualify for free attorneys. Darcy and his colleagues use a list of people who have court appearances that day. They spread their papers out on a small ledge about waist high and shout the names of tenants above the din of the hallway. When they find someone, they briefly screen them to see if they're income-eligible and interested.

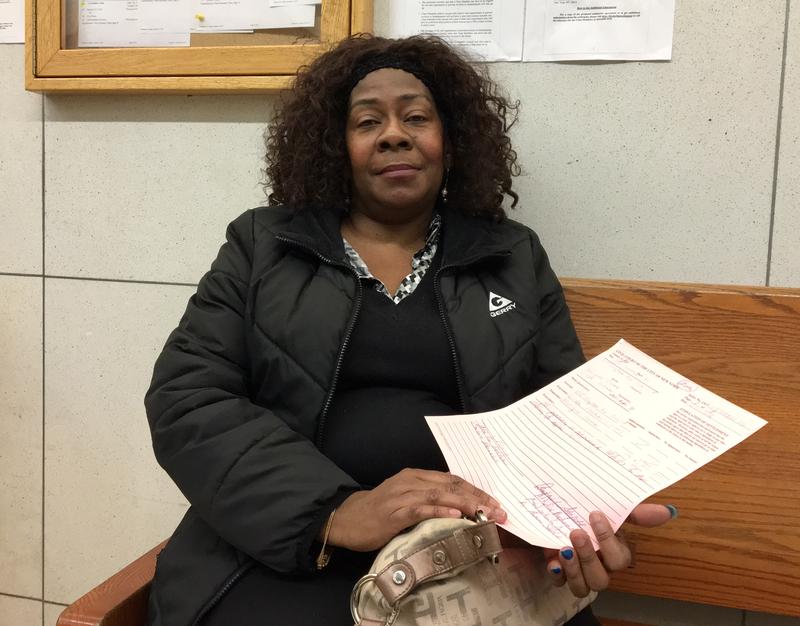

Linda Cooke, 63, was grateful to find out she qualified. She's retired and said her landlord took her to court because she fell behind on her rent. Things got worse when her refrigerator and oven broke down, and she said she's been eating out often, "spending the money I’m supposed to give them, buying restaurant food."

Cooke's new lawyer met with her landlord's attorney and got an adjournment until December. This gives them time to research programs that can help her pay the rent she owes. Cooke said she was exhausted from the experience of coming to court but thrilled to have an attorney.

"At least my mind is at ease a little now," she said. "I didn’t eat or anything and I’m like jittery... at least now I feel little better."

The Bronx has the busiest housing court in the city, with 88,000 filings last year according to the Office of Court Administration. But all courthouses have difficulty finding space for the program, which will only get busier as more tenants obtain lawyers to challenge evictions and complaints about not paying their rent.

The Office of Court Administration said it's appointed a task force to look into the space issue, and a report is due later this winter. There are also efforts to improve the signage. Susanna Blankley, who coordinates the Right to Counsel Coalition, which lobbied for the legislation, said she's now working with the courts and the city so tenants "understand where to go, who to go to, how to access it. That hasn’t happened yet."

Dressler confirmed the city is exploring a public information campaign and more mailings to tenants.

Some of the biggest concerns are coming from landlords. Jeff Hulbert is an attorney for building owners in the Bronx. When tenants are assigned a lawyer, he said that leads to more court appearances, taking longer to collect the rent that’s owed.

"That's money the landlord needs to pay for taxes, pay for the mortgages, pay for fuel costs in the winter if they’re putting this delay on that," he explained. "That makes it harder for landlords to meet their obligations that they have."

He also said the city's investment in free lawyers for low-income tenants could be put to better use funding programs that help tenants pay their rent.

But some believe the law may lead to more efficiency, as landlords file fewer frivolous cases and tenants know their rights. Darcy, of Mobilization for Justice, said tenants need lawyers to explain the complicated rules of housing court.

"Having some time to investigate these serious allegations and people losing their homes is not clogging up the wheels of justice or preventing anyone from getting something that they’re legally entitled to," he said.

Instead, he said, it’s about simply giving tenants their day in court.