In this week’s episode we met a woman whose pancreas is changing medicine. Dana Lewis has Type 1 diabetes, and when it was clear that medical manufacturers were behind on creating the device she needed to manage her disease, she hacked together her own artificial pancreas. Now, over 50 people have built versions of Dana’s system, OpenAPS (Open Artificial Pancreas System).

Dana, like many others in the community, credits Ben West, a San Francisco-based software engineer who was the first to write the essential code that allows patients to hack their insulin pumps and build this mechanical organ. A lot of you wanted to hear more from Ben. So did we.

- How did you get interested in ‘hacking’ Type 1 diabetes and medical devices?

Toward the end of my college career I was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes – after being briefly misdiagnosed. I was using a portable insulin pump and I had to write down all the data from it every day and call and read it to the clinic at night. They told me that there was going to be an implantable version soon, but it didn’t happen. My device was preventing me from sleeping – it would give me chemical burns on my skin. I got pretty upset and started looking at what I could do.

- Tell us what you created.

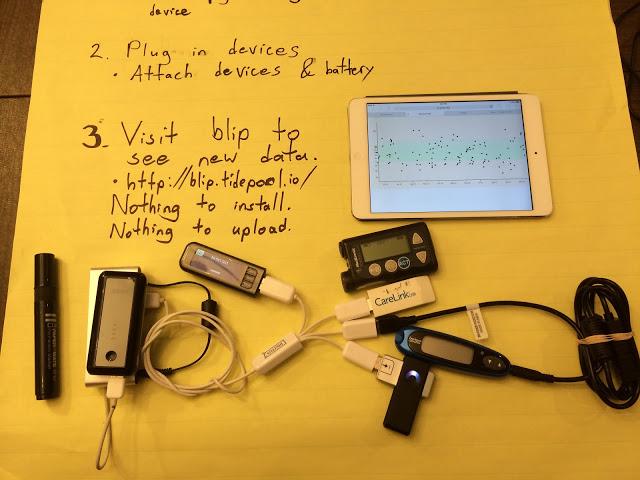

When I started in 2010 to investigate talking to these devices, I thought we might be able to read information about insulin and pump operations from the insulin pump, read information about glucose from a CGM (continuing glucose monitor), or maybe a glucose meter, and then combine it in an application. In 2010, I called Medtronic to ask if they could provide me with the information I needed to talk to the pump, but they denied my request [so I did it myself]. Meeting people like Adrian Gropper and Hugo Campos changed me.

Around that time we starting having hackathons – my brother and sister and dad would get together in the living room and go after this thing. [We were] trying to figure out how time is represented, how the pump responds to different kinds of inputs. Over time, each piece of the puzzle became smaller and smaller.

Finally we had some breakthroughs. I met Scott and Dana several times in 2014, and showed them how to use the tools I had created to issue temporary basal commands [to administer insulin]. For them, this was the last piece they needed in their own DIYPs toolkit to "close the loop." While they got up to speed with the devices, I sat down and dedicated around 3 months of devoted work that spring, and the result is openaps.

- Did creating your own device and “hacking” your own disease change the way you approach your doctors?

I don’t trust them anymore. There’s a loss of fidelity. Years ago, the clinicians told me to keep notebook and write down my experiences and even transcribe data from my pump and glucose meter. It was a lot of work to do, and it turned out they were never going to analyze the chicken scratch I had worked so hard to create, it was for my own awareness.

- Code can be confusing. Do you ever feel responsible or worried about the risks that could come with people creating their own devices?

What’s interesting with the risk is that [traditionally] we’re given a bunch of insulin and we’re told to take it. We hold people responsible for getting it right. That’s not a humane thing, there’s no way you’re going to be able to balance insulin with all your needs.

The way I’ve set up these projects is you have to do something to make it work. You can’t accidentally cause something bad (or good) to happen. We see that when people are unsure they reach out. So this doesn’t bother me at all. The real risk, remember, is diabetes. I often say, I’m not hacking the devices, I’m hacking diabetes.

- Your code is open sourced and the diabetes community is active on Facebook and Twitter. How do you interact with this online space?

I’m not a fan of Facebook or Twitter. The CGM in the Cloud Facebook group has nearly 18,000 people. That’s a place I can go and get saturated with feedback from people who aren’t technical experts like I am. It’s a swath from all over the world. As a system designer it’s one of the best places I can go to get more design input.

Twitter has been good for kind of pushing at the boundaries of these communities to be more inclusive, and connect them to more ideas. The Twitter streams are also pretty good focusing some of the advocacy efforts into a lens.

[Nightscout, the open-sourced glucose monitoring project that helps people track glucose is here.]

- In our episode Dana and Scott talk about their run in with the FDA, which doesn’t approve of sharing information to create these devices. What has your experience been with government authorities?

As a reminder, I'm doing this as a last resort. Why does the market create such an intense pressure that multiple patients are willing to hack their own devices? I don’t see any conflict with the FDA. Their mission is to promote and protect safety. At the core that’s what it’s all about for me. The reason I’m doing this is because I want better safety for myself. I’ve actually worked with the FDA twice, I’ve had two official meetings with them. I’m excited about the possibility of working with the FDA. But right now their process is optimized for the vendors and regulators. I think they need to include patients as equal stakeholders. In practice, that means providing a way for small DIY projects like ours to work together.