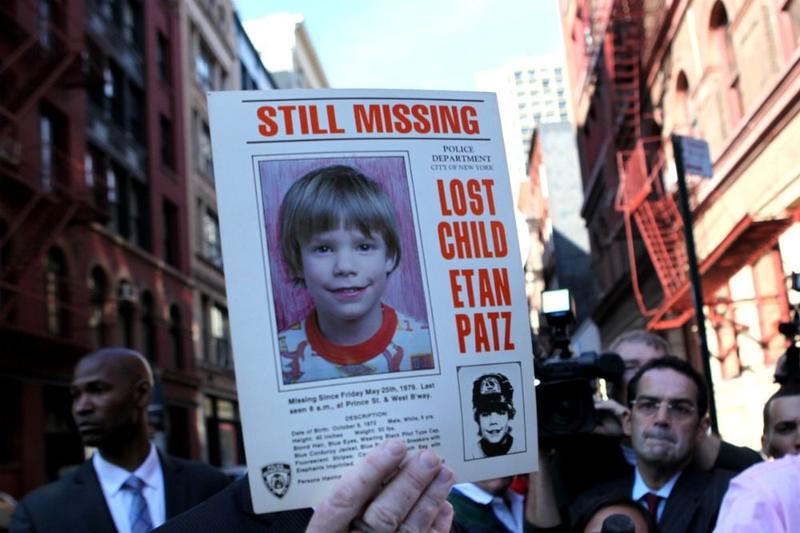

Police Commissioner Ray Kelly stunned reporters — and many long-time New Yorkers — when in May 2012 he said there was a break in the 1979 disappearance of Etan Patz, one of the most well-known missing child cases in the city's history. Kelly announced the arrest of Pedro Hernandez, a New Jersey man, who had confessed to murdering the 6-year-old.

But in getting that confession, detectives did not take what many consider to be a critical step to avoid a wrongful conviction.

They did not record Hernandez's full interrogation.

Court records show they didn't start recording until Hernandez had already been in custody for more than seven hours. That's a fact that could come back to haunt them when the case goes to trial — leaving an opening for the defense attorney to create doubt about the truth of the confession. And if he didn't do it, the lack of a record showing how cops got Hernandez to confess could mean an innocent man goes to prison.

"How in God's name could you not record that interrogation?" said Peter Neufeld, co-founder of the Innocence Project, which works to use DNA testing to exonerate people who were wrongfully convicted. "When you pick somebody up and you know it's a high-profile case, how could you not record that interrogation when you know you're just inviting suspicion?"

The Innocence Project has documented 311 post-conviction DNA exonerations nationwide. In more than a quarter of those cases there was a false confession. Experts say people with mental illness and low IQ are particularly susceptible to confessing to something they didn't do. Hernandez' attorney has argued his client "suffers from a serious mental disorder and has an IQ of approximately 70," according to court filings.

A state task force formed by New York's Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman reported in January 2012 that requiring police departments to electronically record interrogations was the most critical reform possible to avoiding wrongful convictions. Yet months after that report, NYPD detectives recorded only a fraction of Hernandez's time in custody.

Commissioner Kelly was on the task force. State Assemblyman Joseph Lentol was also on the task force and said Kelly actually voted against recommending legislation to require the electronic recording of interrogations. Lentol has pushed for such legislation for the past decade.

One group opposing such legislation is the New York City Detectives Endowment Association. The group's president, Michael Palladino, said it's costly to outfit precincts with equipment and would slow down an already overburdened system.

He worried videotapes of interrogations would "become a training film or training episode for other criminals." He also pointed out that cops in this country are legally allowed to lie and trick suspects into confessing. He worried such tactics might not play well with a jury.

Kelly and the NYPD did not respond to repeated requests for comment on the issue.

In September 2012, Commissioner Kelly pledged to voluntarily expand videotaping of interrogations in the most serious felony cases to all precincts. But more than a year later, two-thirds of detective squads still aren't outfitted with recording equipment, according to figures from the NYPD. Only two of 77 are recording interrogations in homicide cases.

Asked to comment, the NYPD provided a brief prepared statement saying the department is "in the process of expanding citywide."

But that expansion is too late for the Hernandez case. There is a court hearing scheduled for March to determine if Hernandez's confession is admissible.

Reporting contributed by ProPublica reporter Joaquin Sapien.