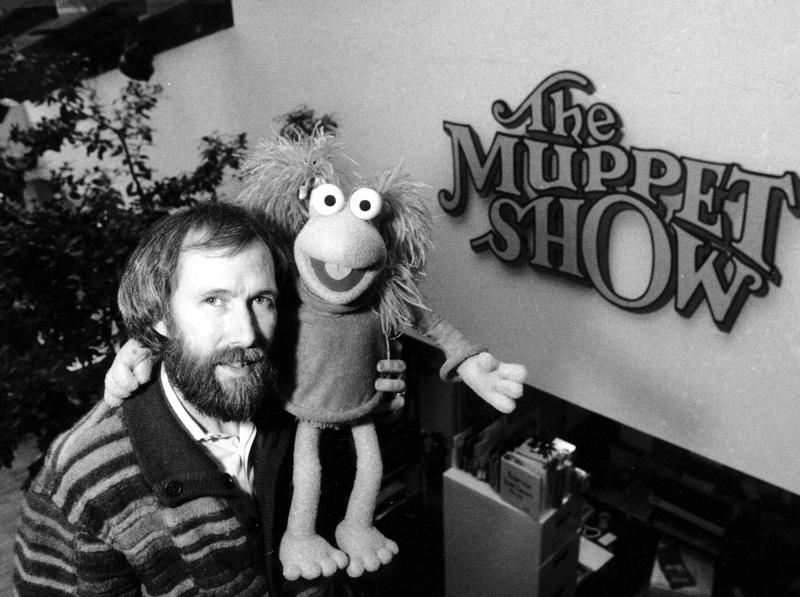

Director Ron Howard's New Film spotlights the work of Jim Henson

( (AP Photo/G. Paul Burnett, File) )

Generations have grown up with Kermit the Frog, Oscar the Grouch and Big Bird. Now Academy Award-winning director Ron Howard takes a look at the man behind the muppets, Jim Henson, in his new documentary "Jim Henson: Idea Man". Ron Howard joins to discuss the film and Henson's legacy.

This segment is guest hosted by Kousha Navidar

[music]

Kousha Navidar: This is All Of It. I'm Kousha Navidar in for Alison Stewart. I moved to the United States when I was one and a half. I am told that I stopped talking for about six months when we moved. While I didn't talk a lot, I did watch a lot of TV, especially Sesame Street. Eventually, I started talking again. I have to believe that that show helped. I've always had a very deep place in my heart for The Muppets and their creator, Jim Henson, and I am not the only one.

That's why I'm thrilled to get things started on the most sensational, inspirational, celebrational, Muppetational chat about Jim Henson on our show. We're talking about a new documentary about Jim Henson, the man with the mind behind your favorite Muppets and Sesame Street characters and Fraggles. It's called Jim Henson Idea Man from Director Ron Howard. It dropped on Disney+ last Friday, which means you can stream it now.

Listeners, we can take your calls about the work of Jim Henson. Call in and tell us how The Muppets or the Fraggles or the Sesame Street crew have been an important part of your life. You can get to us at 212-433-9692. That's 212-433-WNYC. You can text us at that number too if you want or maybe you've already had a chance to see the documentary, which is Jim Henson Idea Man, and it's been streaming for a week on Disney+.

You can call in and ask Director Ron Howard a question about the film or, and I would love this, if you have a story about meeting Jim Henson or having a chance to work with Jim Henson, call in with that story too. We're at 212-433-9692 or hit us up on social. We're @AllOfItWNYC. Joining us now to talk about the documentary, I'm very lucky to be sitting right across from the table from the director, Ron Howard. Ron, thanks for joining us today.

Ron Howard: A pleasure. Real pleasure and I look forward to talking to people. I'm sure I'm going to hear some stories that we wish we had in the movie, but we had so much footage, so many comments, so many great bits, musical numbers. I love where we landed with the film, but it really was a process because there were so many great creative opportunities because he and his team were just so prolific beyond even the stuff that we're all most aware of, Muppets.

Kousha Navidar: Yes, absolutely. How did you decide where to point the laser or where to point the aperture?

Ron Howard: You know what? When you're working on a documentary and, of course, I moved back and forth these days, these last 10 years between scripted movies and television projects and documentaries, you do take a lot of leads from new information sources. You'll do an interview and somebody says something really interesting. You do a little research and follow up. Suddenly, you find a clip that reinforces that in some way. It becomes a building block maybe in a new sequence or a scene within the documentary.

You start building around the idea of sequences. What are the pillar events? What are the things you know you must deal with? Out of those, you begin learning more about the person, more about the process. I'm always fascinated by process and the journey. Somebody was telling me. I turn every film into some kind of a survival story. I don't know if that's exactly true, but I am interested in how people get from here to there. In this case, there was also a really interesting family story I felt underneath it.

Kousha Navidar: Was that one of the first themes that really approached you as that family?

Ron Howard: Well, that was a big surprise because I knew quite a bit about Jim. I'd done some reading about Jim. When I met the family and I recognized what a whirlwind he created in the most positive, playful, loving way, but this non-stop creative engine of his was inspiring. Of course, there's a human side to it and even a cost. His wife, Jane, the two of them together built the Muppets. They were partners before they even really fell in love and romantically connected and ultimately married.

It's also interesting that that was its own journey. Ultimately, they drifted apart. In a way, the thing they built wound up pulling them apart. There's something very human about that. At the end of the day, they did a good job with that aspect of their lives as well because I could see these kids. I could hear them talk about their parents and recognize that there was a lot of love. There was a lot of respect there even if there was some sadness that they hadn't been able to go the distance as a couple.

Kousha Navidar: What surprised you about the family story? Was it the cost or was it something else?

Ron Howard: Well, I just didn't know anything about Jane. I really didn't. I thought that was an interesting element that even somebody as brilliant as Jim and he was characterized as a boy genius. Creatively, in his high school and first years in college, people just knew he was one of those guys, but it wasn't about puppets. He didn't really have any interest in puppets. He met Jane in a puppet class, but there you go. He's not interested in puppets, yet he takes a puppet class. Why? Because he's curious. That's what's driving him.

She recognized this gift. She was a few years older and I think really helped give him direction and focus and help him know what he had to do and how he could use his creativity and make it his life's work. They established that together. The other thing I didn't know was what might have fueled that race against time. His own Academy Award-nominated documentary-- short film, sorry.

Kousha Navidar: Short film, yes.

Ron Howard: It was called Time Piece. You can see it online. It's great because as a filmmaker, you realize how ahead of the curve it was stylistically. It was very modern and very avant-garde and experimental and still funny, still witty, still very Jim Henson. In fact, you see a lot of what you'll find years later, you're going to see on Sesame Street in his experimental work, but what was it really about? It was really about a guy who was just searching, just trying to find his way in the world and racing against the clock.

All kinds of crazy impulses and crazy obstacles were coming his way. He was just paddling upriver as fast as he could. Every once in a while, you cut to a crazy shot of him, head in a toilet bowl or dangling from something saying, "Help." He was aware. He knew that there was a part of him that could just never really be satisfied. I think that was also some of the rocket fuel that gave him the energy to give us all those iconic characters that we remember.

Kousha Navidar: That term "aware," I think, is so important. When I was watching the documentary, the whole Orson Welles clips really struck me. Orson Welles described Jim Henson as Rasputin but as an Eagle Scout. That's quite discouraging.

Ron Howard: I think he was going with the look. Jim had the kind of the beard. I don't think he had any Rasputin characteristics, although he did have people who were devoted to him. We interviewed some of them and I've met many others, but he wasn't diabolical. There was nothing manipulative about him. He found it fun. He made good, logical sense to people because why not make something great? "Let's go do it. Why not take this funny character and do something unexpected with it? Why not push the boundaries? Follow me. Come with me." He led by example minute by minute.

Kousha Navidar: If you are thinking about your work as being-- you said you were bouncing between scripted and documentary features for a while. How is it for you going with the flow? Do you often find it difficult to have your preconceptions either challenged and to adapt on the fly as you're doing? Is it a different muscle for you versus when you're scripting?

Ron Howard: Well, [laughs] I love hanging around and spending time with the pure documentarians. They're like journalists at heart. They're asking questions and seeking answers, whatever the tone of whatever they're working on might be. They're also used to that particular high wire. I've kind of stopped asking the question. For the first four or five documentaries I made, I remember getting to about a halfway point where we'd have lots of footage collected and edited together in various buckets because that's what you do.

You don't really worry about a story sequence yet. You just collect all the information and then you start to see ways to build a narrative. I literally once just put my head in my hands and looked up after looking at an editorial session. I said, "Is this a movie? Do we even have a movie?" They all laughed at me, kind of the way you're laughing and nodding your head now, which is, "Just relax, Ron. We're all pros at this. We're doing fine. We're ahead of the curve believe it or not."

The late great Jonathan Demme was the guy that actually urged me to finally get into trying to move from scripted and experiment with documentaries. We were both board members at Jacob Burns Film Center. I was contemplating getting involved in a project. I asked Jonathan about it and he said, "Oh, go for it." He said, "You're going to use a lot more of your muscles than you realize. It's not that different, but you have to go in with a plan, a point of view. You think you know the story, you think you know what you're looking for, and just be ready to be wrong." This is a different thing than having a screenplay.

Yet, when you work on scripted stuff, there are a lot of surprises. I think the documentaries in some ways are helping me to relax a little bit and not only follow the script but also look for those surprising turns, take advantage of a moment. I'm also learning a lot more about real human nature and how people respond and the surprising ways in which they do when there can be much bigger than life than you ever would've guessed or the way they cope with something is to get real small. There are extremes of human behavior that I'm actually understanding more from working in the documentary side of things than working with the world's greatest actors.

Kousha Navidar: Sometimes the truth is stranger than fiction.

Ron Howard: Oh, almost always.

Kousha Navidar: Almost always.

Ron Howard: Which is why I've done a lot of movies based on real events. Apollo 13 was my first. That came out in, I think, '95. Brian Grazer and I had imagined both have come to really look for those projects. We're still into fantasy, still into comedy. Happy to do Nutty Professor, but there's something about finding the thematic values in those stories and sharing them whether it's through the documentary side of things or scripted where you're using great actors and directors and the artifice of the medium to try to transport people in that way.

Kousha Navidar: That exploration, that transportation, is such at the heart of Jim Henson's work too. It was wild to me how he didn't even think about being a puppeteer, to begin with. It's just a medium that he wanted to do it through.

Ron Howard: Well, it was TV and this interested me because I started thinking about this and I thought, "Oh, that was the new tech." For him and Jane, that was the latest, most interesting thing to possibly work on. What did they do? Experimental, short-form entertainment where they started to pick up an audience and started to understand their voice, how it worked, how it landed, what it meant to people, what they could learn from it, where else they could take their talent and their interest and their point of view. What do content creators do today? That's the experiment they're engaged in.

Kousha Navidar: I thought about that exactly, yes.

Ron Howard: For them, that was somehow getting a five-minute spot on late-night television in the local station. Today, it's TikTok or getting on YouTube.

Kousha Navidar: Absolutely. It's wild how the parallels work out there. Listeners, we're talking to Director Ron Howard about Jim Henson Idea Man. It's a documentary that's streaming now on Disney+. We're also taking your calls. We got to go to a break soon, but I want to be sure we get at least one caller in. You can give us a call at 212-433-9692. If you've got a story about Jim Henson or you want to talk about how his work and Jane's influenced your life. Let's go to Debbie in Sussex County, New Jersey. Hey, Debbie, welcome to the show.

Debbie: Hi. Mr. Howard, may I call you Ron?

Ron Howard: Please do.

Debbie: I just want to thank you so much for the documentary. I just watched it and I was fascinated by all the aspects of Jim Henson's life. I didn't know he was from Mississippi. He was such an amazing artist. He wasn't just hands-on. He was hands-in into all his puppets literally. I just had a wonderful experience once before Jim passed away and I really regret.

I remember wanting to take the day-off from work to go to his amazing funeral. I was very good friends with the author, Isaac Asimov. Isaac was invited to do an interview from Muppet Magazine. Then, it was called HA! Associates. We went in. There was everything you could ever imagine a workshop with Muppets might look like. It was where they first created the prototypes of the Muppet Babies and every detail was there.

They were taking pictures for a calendar called the Kermitage, where they would duplicate classic paintings using Kermit instead of a traditional Rembrandt or something, but what I also wanted to say to you was happy birthday because you and Spielberg and Oprah Winfrey and a bunch of other people, we've all turned 70 this year. Happy, happy birthday to you too.

Ron Howard: Thank you.

Kousha Navidar: Debbie, thank you so much for that. Wonderful birthdays all around. We're talking to Ron Howard, the director, about the film, the documentary, Jim Henson Idea Man. We got to go to break. When we come back, we're going to talk more about Jim Henson's life, what it meant to make this documentary, and definitely take some more of your calls and texts. Stay with us.

[music]

Kousha Navidar: You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Kousha Navidar and we're talking about Jim Henson. Specifically, the documentary, Jim Henson Idea Man, which is streaming now on Disney+. We're here with Ron Howard, the director of the documentary. Listeners, we're taking your calls about the work of Jim Henson. If you have a piece that really made a difference in your life or you have a story about Jim Henson, give us a call. We're at 212-433-9692. Ron, before the break, we heard from Debbie in New Jersey about the details that you can see in Jim Henson's work and that kind of incremental development, right?

Ron Howard: She was knocked out because she went in and saw how they were all made. When I visited in making the documentary and preparing it, it just reminded me also of what you would see in the creature workshops at Lucasfilm and Industrial Light & Magic. It's just a reminder. Yes, the premieres were great. It's not really was his thing, getting good ratings. Of course, he wanted to succeed, but he was all about process and everyone around him was.

It was about the joy and the patience required to just, beat by beat, step by step, keep advancing a creative idea. For him, it was play. It wasn't drudgery, but it still required discipline and it still required follow-through. I hope people, when they watch the film, pick up on that because there's a lesson in it because nothing just happens. Nothing remarkable just happens.

In fact, when I look at those experimental films in Sesame Street, that's what really blew my mind. I didn't know that much about the Muppets or Jim Henson back then. When I saw Sesame Street and saw this tone and this style and it was so cool using the animation and the stop-motion and all of those things and the syncopated soundtracks, I just thought it was cutting-edge stuff. It made me sit and want to watch Sesame Street with my kids.

It wasn't until later that I realized, "Well, all that stuff is just a function of a couple of decades of him experimenting, whether it was his home movies or he had his own animation stand where he would tirelessly create these little stop-motion animations with pieces of material and things that are just so visual and cool." We use some of them in the film. It's inspiring to remember that creativity is not just for genius-level people, but it does require a follow-through.

Kousha Navidar: Yes, and discipline and every piece--

Ron Howard: Just do it. Make things. Everybody around Jim just said, "He just liked to make things." That's the way his family felt. They were raised to make things.

Kousha Navidar: We've got a text in here that I think is especially pertinent. It says, "I highly recommend that everyone check out the Jim Henson exhibit at the Museum of the Moving Image. It's so lovingly curated and brought me to tears. It shows everything from high school doodles to early Muppets to his more obscure work like his collaborations with Raymond Scott. Where else can you see David Bowie's costume from the Labyrinth complete with codpiece?" Shout-out to that movie, Labyrinth.

Ron Howard: Absolutely. That's good advice. It's a great way to spend some hours and really fun.

Kousha Navidar: We've also got a couple of callers I want to get to. Here is Jack in Brooklyn. Hey, Jack, welcome to the show.

Jack: Hey, can you hear me?

Kousha Navidar: Yes. Hi.

Jack: Yes, hi. You were talking about watching Sesame Street with family. It brought to mind when I was a kid in the 1970s, my parents were immigrants from Eastern Europe, and we would both watch Sesame Street and basically learn English together. It wasn't a conscious effort. Basically, my parents would be watching Sesame Street and learning language lessons the same way I did as a kid.

Kousha Navidar: Jack, thank you so much for that.

Ron Howard: That's an amazing story. It makes absolute sense to me, but what was great is that he was really an entertainer and a communicator. As we say in the documentary, he didn't think he was going to be an educator per se. He just wanted to entertain and share the results of his playtime with people.

Kousha Navidar: Well, it's interesting because in the documentary, it also talks about the next thing he wanted to do after Sesame Street, how that influenced the way he wanted to take his career, wanted to push against it a little bit.

Ron Howard: Well, he wasn't really a careerist because, otherwise, the Muppets would probably still be on.

[laughter]

Ron Howard: He left after five years when it was a top show. He wanted to leave Sesame Street in a way, and then he didn't leave because he realized he could still do other things and still make a commitment to Sesame Street, which he maintained throughout his life. Part of Jim's problem is he created so much that he still had a finger in and still had involvement with that his life was becoming so hectic and so around the clock. He was living life he wanted to live, all too short. We lost him far too young.

Kousha Navidar: Let's go to Paul in Brooklyn. Hey, Paul. Welcome to the show.

Paul: Hi. Can you hear me?

Kousha Navidar: Yes. Hi.

Paul: Hi. I wanted to tell the story of going to Jim Henson's funeral at the Church of St John the Divine in 1990. I was living in that area and it was an open funeral, so anybody could go. It was a tragic event obviously. I remember distinctly, a lot of very sad Muppets around the church. I believe I remember the Big Bird saying, "It's not easy being green." It was just a devastating moment.

Ron Howard: Well, there are scenes in the documentary of that funeral and it will bring back memories. It's very emotional for everyone who was there. I hope we reflect some of that emotion through the film, but there was also a sense of joy. His son, Brian, was speaking and reading something that Jim wrote. It's funny and it's irreverent and it's satire. At the end of the day, whether it was gentle or cutting-edge, Jim was a silly satirist. Whether they were making TV commercials back in the '50s and '60s or doing the Muppets later, they were always finding that way to hold a mirror up to ourselves and say, "Aren't we getting a little ridiculous? We are. Come on," and use the puppets to achieve that.

Kousha Navidar: Let's go to Rachel in Nyack, New York. Hey, Rachel. Welcome to the show.

Rachel: Hi. I wanted to share that my brother, Richard Hunt, was one of Jim's first original Muppeteers as well. He was hired on the same time as Fran Brill, who you interviewed. The reason my brother isn't there to be interviewed is that he died about nine months after Jim during the AIDS crisis. Richard was in those letters that Jim left behind with instructions for his funeral that you just talked about. He had asked that if Richard Hunt was still alive to please have him emcee and direct that funeral. My brother coordinated and put that funeral together that that person was just talking about, which is pretty amazing-

Ron Howard: Yes, it is.

Rachel: -that he just said that. Actually, I've had a lot of people say to me, "I'm sorry. We didn't get to see Richard in that," but that's okay. What I was going to say also that I wanted to add is something that Frank said and I had the great fortune of-- Richard was nine years older than I, so I got to grow up on Sesame Street too because I was-- Jim hired him straight out of high school just like he did Frank. My brother called Henson. They answered the phone.

He said, "Hi, I'm a puppeteer. Do you need anybody?" They said, "Well, as a matter of fact, why don't you talk to Mr. Henson?" He's like, "Okay." He called from a payphone in the city and they told him there were auditions the next day. Jim's ability to choose talent was beyond what anybody else has had since. I think that's one of the reasons that Muppets, and I don't mean to be mean, but it's not the same since Jim died. He could choose the most talented people in the most amazing way. I just wanted to add--

Kousha Navidar: Rachel, thank you so much. We're going to have to pause you there for time, but we really appreciate that comment.

Ron Howard: Thank you for that.

Kousha Navidar: Yes, and especially the eye for talent. Do you want to talk about that a little bit?

Ron Howard: Well, definitely the eye for talent, and also what we had to leave out of the documentary because there are so many people like Richard and so many others on the musical side as well that were, at one point, a part of the documentary just as we focused it and made it movie-length. It's always a bit of a struggle, but thank you for calling in. He had a great eye for talent and, by the way, so did Jane who said, "I found him. I found Jim Henson by the way," and she did, but she also helped with that recruiting and identifying talent. He found people. It wasn't like they had to do it his way. They just had to want to play and invent and create. The esthetic grew out of the community as much as it did out of Jim.

Kousha Navidar: We're running short on time and there's so much to get to, so I just want to thank listeners first for all of their input. Ron, got less than a minute left, but you're a storyteller, so is Jim. What are some of the things that resonate with you that maybe you'll carry forward with the way Jim approached storytelling?

Ron Howard: His willingness to take risks. I like to believe that I share that, but I think he's a supreme example of somebody who, despite success, never desirous of financial success for what it meant to his company and his life, sure, but never prioritized that. Always prioritized exploration creatively and seeing what he had to offer that he could share.

Kousha Navidar: The director is Ron Howard. The movie is Jim Henson Idea Man. We have been listening to Ron wonderfully talking about Jim Henson and all of your calls. You can take a look at it on Disney+. It's streaming now. Ron, thanks so much for hanging out with us.

Ron Howard: What a pleasure. Thanks.

Kousha Navidar: That's it for All Of It today. Coming up tomorrow, a lot of people say they want to find a third place, one that's not work or home, but a spot where they can hang out with friends and neighbors. On tomorrow's show, we're going to talk about how to find one of those places. Stay with us. We'll talk to you tomorrow.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.