Election Integrity and National Security

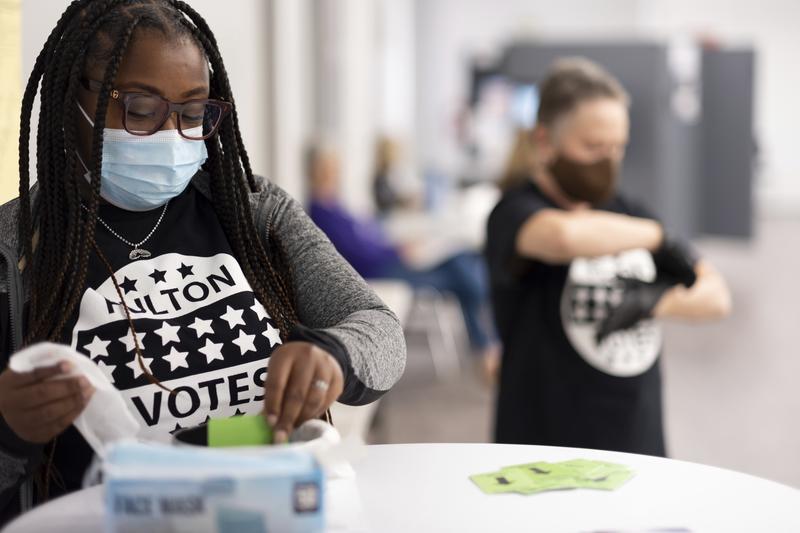

( Ben Gray / AP Photo )

Julian Zelizer, professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University, CNN political analyst, NPR contributor, and author of several books, and Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law, the author of several books, discuss the new book they co-edited, Our Nation at Risk: Election Integrity as a National Security Issue(NYU Press, 2024), in which experts weigh in on the risks to national security posed by election insecurity.

[MUSIC]

Matt Katz: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC, welcome back, everybody. I'm Matt Katz, keeping the big seat warm for Brian today. From armed citizens patrolling ballot boxes to widespread disinformation about election fraud, there are serious threats to the stability of our democratic process. When the integrity of our elections is threatened, so too is our national security, and that's the key takeaway from a very timely new book called Our Nation at Risk: Election Integrity as a National Security Issue.

Its editors, who will join me in a moment, have brought together some of the nation's top political scientists, historians, and legal scholars for a blunt assessment of this precarious moment for American democracy, as well as a look at how we got here. My guests are Julian Zelizer, a professor of History and Public Affairs at Princeton University, CNN political analyst, and NPR contributor. Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law.

Again, they've collaborated to edit this new book, Our Nation at Risk: Election Integrity as a National Security Issue. Professor Zelizer and Professor Greenberg, welcome back to WNYC.

Julian Zelizer: Thanks for having us.

Karen Greenberg: Thank you.

Matt Katz: Great. Professor Zelizer, what do you hope readers take away from this new book, and how do you see it contributing to this ongoing conversation that so many of us are having, about the future and the survival of American democracy?

Julian Zelizer: The first thing is to take a long-term view of the problems we face today, rather than seeing it as a snapshot, rather than seeing it exclusively through the prism of issues related to former President Trump. To see, over the course of history, some of the vulnerabilities of our election system, and why they have, in some ways, become worse in recent years.

Second is to think of the integrity of our elections as fundamental. We are not secure as a nation if our democratic process is not working, and this is as important as some of the military precautions the nation takes to secure ourselves. Finally, to really take apart the different elements of what the issue is, from election administration to information in the media, to voting rights, and more.

To really systematically have some of the best and brightest minds unpack what we should be thinking about when we attempt to reform and make sure that our democracy is working well.

Matt Katz: Two of the best and brightest minds in the book are yours. You both contributed essays to this collection. Professor Greenberg, the first essay in the book is about contested presidential elections. This is something you wrote, "If the 2000 election was a wake-up call and the 2020 election a full-scale alarm, other elections had also stumbled to the finish line." That's what you wrote in this essay.

Can you give us some of the historical precedents for the full-scale alarm of 2020? I felt, "Oh, this has happened before." There's been issues before, but also, it felt like it's building to a larger thing. Give us a little historical context there.

Karen Greenberg: Thank you so much for pointing out the sort of yin and the yang of this, which is, should we be alarmist, or should we say, because this has happened before, we know how to get through these things? I think that is a good introduction to what's happened in the past, and there have been so many elections that have been contested. The election of 1800 has its own vulnerabilities. The well-known election of the late 19th century, Tilden/Hayes election.

As you said, the 2000 election, and others along the way, that were more minor in terms of repercussions and echoes of them, but they were also very alarming. What's interesting about each one of these elections that I've talked about, not to mention 2020, is that there have been responses on the part of legislatures at the state level, on the part of the federal government, and on the part of a number of administrative bodies, to fix what's gone wrong in those elections I mentioned, and in other elections along the way.

It's not that we haven't been mindful as a nation of the different vulnerabilities that have been exposed, election after election, the problem is particularly, now, at this point in time, that we haven't fixed enough of those vulnerabilities, because, in fact, it is hard. In part because of the split in election administration and policy between the federal and state government, but also because right now, so many new issues have emerged that were not there in the elections prior to 2020 that I'm talking about.

Particularly, for example, in the areas of disinformation and how that functions via the social media sphere and other ways, in terms of how we're going to deal with a ballot. What are we going to do about the counting of the ballot, paper ballots, electronic counting, and how to exactly establish a uniform policy for that and other things? Then the third thing that needs to be mentioned in terms of the new level of how we've dealt with threats in the past, as opposed to what's confronting us now, is the way in which, right now, so many of these fissures and potential vulnerabilities, despite our fixes, despite even recent fixes, since 2020, overlay one another, and so are hard to separate and to fix in a wholesome and wholesale way.

Matt Katz: Also, Professor Greenberg, the other element that I imagine didn't exist there in the same way, and maybe the election of 1800 is this global anti-democratic movement. Your work has often focused on national security. How does the integrity of our elections intersect with broader national security concerns, especially given other global anti-democratic movements out there?

Karen Greenberg: No, it's a really good question. You look at what's happening around the world. You look at what's happening, and we have over 50 elections worldwide this year. The United States has always positioned itself as the country that does the best job at democracy, the one to be able to set the path for how to solve the problems that beset democracy, and a shining light.

I'm giving this a nice, rosy-colored dimension, but I think it's accurate. The shining light for this is how you do democracy. This is how you overcome the problems that we encounter. That's one aspect of it. Another aspect of it is the success that's been reported about disinformation in many of these foreign elections, foreign disinformation as well as some domestic disinformation, and how that has played in elections, where we see that the powers that be have not been able to deter them in an effective way.

A third thing being the violence that accompanies a number of these elections around the globe, and this general instability of what is a fundamental element of democracy. I think you're raising a very good point. Where does the United States fit in this escalating undermining of elections as perceived to be fair, safe, trustworthy, and accepted as trustworthy in their result? I think that's a question that remains to be seen.

I'd like to give you, "Don't worry, we're going to do what we always do." I do think that it makes a little bit for more insecurity, a little more worry, more consternation in terms of approaching our own elections, but it also has led to fears around the world, about what can happen in our elections, and what that mean for their countries and the countries they're allied with. Thank you so much for that question.

Matt Katz: I want to switch gears slightly. Professor Zelizer, you wrote about Selma, in 1965, subsequent passage of the Voting Rights Act. Can you talk a little bit about that? How does that historical moment inform our understanding of today's challenges when it comes to voting rights and election integrity?

Julian Zelizer: For me, there's two different elements that are important. One is to remember that the struggle over that legislation which passes in 1965, Lyndon Johnson's President, you have a Democratic Congress, it comes after the Civil Rights Act of '64, it's a reminder of how fragile the commitment to voting rights actually has been in this country. That was an effort to overturn the Jim Crow laws of the Deep South, which had reversed the progress of reconstruction.

Racial disenfranchisement, as I try to point out in the article, is just one way in which the struggle for the vote has been extraordinarily difficult. There's been often as much pushback as there is push for people to be able to exercise this right. That Voting Rights Act in '65 is a reminder of that, which I think is relevant today. The legislation had a deep impact. It allows for a dramatic rise in Black registration in states like Mississippi.

Becomes, really, a pillar of several decades when voting rights is much more stable than at any time in American history, but the second part of the essay is that since the 2010s, we've seen a reversal of that commitment. The legislation itself was undermined by the Supreme Court in the Shelby v. Holder decision, and we've seen, in many red states, efforts to put back onto the books voting restrictions, sometimes not as direct as the ones that previously existed, but which have the potential and sometimes do dampen voting.

We're in an era where I try to show that we have moved far away from the promise of 65, and it's incumbent on legislators to work on restoring what that 65 legislation had achieved.

Matt Katz: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. I'm WNYC reporter Matt Katz, filling in for Brian today. My guests are Julian Zelizer, Professor of History and Public Affairs at Princeton University, CNN political analyst, and NPR contributor, and Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law. Together, they're the editors of a new book, called Our Nation at Risk: Election Integrity as a National Security Issue. Listeners, we can take your questions on this topic.

Text us, call us, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. We had a listener who texted in and was hoping that you guys might be able to respond to something that Republican nominee Donald Trump said the other day. The quote is, "Christians, get out and vote, just this time, you won't have to do it anymore. Four more years, you know what? It'll be fixed. It'll be fine. You won't have to vote anymore, my beautiful Christians."

The listener asks if that statement represents a threat to election integrity, this inference that after he's reelected, there will not have to be more elections because he will just remain in office. That seemed to be what he was saying. Either of you want to tackle that?

Julian Zelizer: Sure. Look, there is the rhetoric of the former president, and he is often intentionally provocative in his ongoing efforts to shape what the media is talking about, and to keep attention on himself. I also think there are very real concerns, not about having what he said play out, but I think what Karen and I are both talking about is, the problems with the elections are very real.

We lived through January 6th, we've seen the voting restrictions, we see them on the books, and we see other problems of poll workers being scared, et cetera, et cetera. When you have a whole infrastructure of problems and he makes a comment like that, and he himself has been part of an effort to overturn a presidential election, I think we should take it seriously. Not that that is around the corner, but a reminder that his administration certainly was not committed to making the democratic process stronger.

Karen Greenberg: Yes. [crosstalk] Let me just add one thing. One way that that's been interpreted, I think, by people who realize what a destructive comment it was, and in an effort to dig the former president out of the hole was-- what he meant was that he would turn the country into a country Christian nationalists want. They wouldn't need to vote anymore, because they'd already have the country they wanted, which is, in some ways, as disturbing as we won't be-- The suggestion that, "I'm going to erase the need for elections overall."

I just want to add that this is where the issue of Project 2025 comes up, because the one word that comes across more than any other in the project, which is over 900 pages, is dismantling. It really is about dismantling the processes, the legal parameters, and the country as we know it. I'm really glad that you brought up that statement, because I think it goes to the heart of what the former president sees as his efforts to undermine and dismantle democracy as we've known it for so many decades.

Matt Katz: Project 2025, of course, is this platform from some on the right, that they want to see Trump implement, if he were to win reelection. Professor Greenberg, in one of the essays, Nicole Hemmer, who's a political historian focusing on the media, discusses disinformation, which I think you mentioned earlier, and throughout the book, the role of major news corporations in spreading disinformation about election fraud comes up.

How has the disinformation campaign evolved, and what impact has it had on public trust in the electoral process? Is it fundamental to this erosion in public trust?

Karen Greenberg: I think it is fundamental. I want to say that yet, Nicole's essay, which is terrific, there's also a way in which Jeremi Suri's essay talks about it as well. Talking about both foreign influences, domestic influences, different kinds of disinformation, I think that we haven't, as a country, paid enough attention to this term. We've tied it to the social media atmosphere of recent years, rather than understanding how it's been a part of so many elections, of trying to mischaracterize the president or the candidates that are coming up.

It's not new to the American scene, but the intensity of it, the frequency of it, is immense. I want to just say we think about disinformation of these larger political agendas that get spelled out, this is what the president's going to do, this is what he said, this is what is going to happen, but there are other ways in which disinformation is really important, that seem to be at a much more granular level, and that is the use of disinformation or robocalls for people who have already been convicted of this in recent times.

Robocalls that say, "Oh, you know where you thought you were going to vote? The voting place has been changed. Oh, you know that the bus that was going to take you to the voting place, we're going to take that bus elsewhere." Using disinformation as voter suppression, not just in terms of what people are hearing and responding to in terms of political rhetoric, but in terms of where they think they should vote.

I think this is a overlooked aspect of what we mean by disinformation and just how pernicious it could be, particularly at this moment in time.

Matt Katz: We have a caller that I think is going to get a little bit to that point. Joel, in Union, New Jersey. Hi, Joel. Thanks for calling in.

Joel: Yes, thanks very much for taking my call. Yes, I've been involved in election integrity at the left forum, in various places. I keep up with Greg Palast, who's making another documentary on the efforts, especially in Georgia, to disenfranchise tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of voters. They question their eligibility to vote and then force them to vote-- I'm parked, but I'm trying to turn off my GPS. [unintelligible 00:17:00]

Matt Katz: [crosstalk] Sure. I'm glad you're parked, Joel.

Joel: Then, on democracy now, I heard about this organization on the right, Ziklag, or something like that, which is trying to automate the disenfranchisement of hundreds of thousands of minority voters. This is a very, very real threat, and it requires legal action, which Palast is leading. I just want to know if they're familiar with Greg Palast's work, and if they're familiar with Brian Kemp's shameful record in suppressing votes in Georgia.

Matt Katz: Thanks for the call, Carl-- I mean, Joel, excuse me. Either of the professors want to tackle that?

Julian Zelizer: Sure. I'll jump in. Yes, I think Georgia has been a state that has been examined. It was in the eye of the media, certainly, and voting rights defenders, when Stacey Abrams ran, the issue came up. The efforts to either purge people from the rolls or put on restrictions that are unnecessary, has been an issue. It was an issue in the 2000 election in Florida that was part of the battle, although it's often overshadowed by a recount.

Yes, those are the mechanisms that voting rights advocates are fighting against right now. The Trump administration had been very supportive of those, and the Biden administration was unable to move forward in legislation that would prevent a lot of that from happening. I think that's going to be on the table in the coming years, and I think the caller is pointing to one of the big issues that I and some of our authors tried to highlight, in where we are today.

Matt Katz: Professor Zelizer, the public trust in this process, given what's happened over the last several years, seems to be really collapsing. Public trust in the electoral process is just crucial for a functioning democracy. How is that trust rebuilt, especially among communities that feel disenfranchised, either rightfully or not?

Julian Zelizer: Yes, look, there's many things that go into that distrust, but certainly, making it harder to vote doesn't give people a very good feeling about the election system. It's not a surprise that in many Black American communities, this is an issue that is front and center. I think that's important. I do think the media issues that Nicole Hemmer writes about, and Karen just spoke about, are important.

A lot of the disinformation out there, certainly in 2020, has just led people not to think the system works, even when it works much better than we think. This is, in part, where not only does the media need to be careful in thinking and contextualizing information that gets out there. Our elected officials have a responsibility not to spread false claims about the election not working where it's working. They also need to take care to prevent efforts that are actually weakening the election system.

Those are big asks from many different institutions and some political officials who have very different incentives. Unless we do all of that, you're going to have big parts of the population not thinking much about the democratic process, and that can result in them participating much less.

Matt Katz: We have a call from--

Karen Greenberg: Can I add something to that?

Matt Katz: Oh, please.

Karen Greenberg: Oh, go ahead. No, no. Take the call.

Matt Katz: Professor Greenberg, go ahead. No, no, no. I want to hear what you going to say.

Karen Greenberg: I was just going to say that one of the things that really disturbed me about putting together this book, and Julian and I have talked about this. The attention to all of this is that we seem to throw up our hands in despair, like, "Oh my God, there's all these threats. What are we going to do?" They're each one legitimate, as Julian just emphasized in his last comment. I also want to say that is-- three things.

One is, we have done a number of things inside the government to build up protections against what we are expecting and what we know is [unintelligible 00:21:23], both the election threats task force that's set up within the Department of Justice, the Electoral Count Reform Act that happened in 2022, that, tied to streamline, put guidelines around how the vote is certified in Congress, and then the rejection by the Supreme Court, of the Independent State Legislature Theory, that legislature are not free from review by state courts.

All of that is to say that there is a tremendous opportunity in this election. Even though we come to it with fear, with a knowledge of all of these problems, the opportunity to do this election in a way that rings true, that restores trust, that makes people know that the election system works, even though it seems like a far cry, is doable, there are a number of entities trying to approach this and to rise to the occasion. I just wanted to put that out there before we descended into tremendous despair.

Matt Katz: No, thank you for the dose of optimism. Let's see if we get more of that, or the opposite, from Paul, in Sun Valley, Idaho. Hi Paul, thanks for calling in.

Paul: Hi. Thank you. Thank you for this show. My question has to do with a big concern I have in the upcoming presidential election, the certification of the vote. Obviously, we know that the vice president certifies the votes, but is there not certification that occurs at a lower level prior to when the vice president has to certify the vote in the Senate? In other words, is there certification that has to happen first at the county level, and if so, what do we do if a large number of Republicans at the county level refuse to certify the vote?

Matt Katz: Interesting. You guys do delve into how certification process works, how that has changed through the years. Which one of you can help shed some light on that question?

Karen Greenberg: How about I start, and then Julian fill in all the spaces? That sound good, Julian?

Julian Zelizer: Sure.

Karen Greenberg: Okay. What I was going to say is that the Electoral County Reform Act, and other things that have gone on in different states, have addressed this. You are right, there are concerns from the last election, also concerns that a lot of the appointments that have been made to election boards, and even some of the poll workers who'll be put into place, have been put there to work in a certain political direction, and therefore are considered to be, by many, [inaudible 00:24:10] worried about that they will be untrustworthy in the ways that the caller has mentioned.

There has been some streamlining, though, and some clarification of what can be done and what can't be done. Among them, not just at the Vice President's role, is just ministerial, and is not there to consider whether or not to review some of the votes that's been taken out of the vice president's hands in a very declarative way, but also at the lower level, who gets to say what's the certified vote, and how it gets passed along, has all been clarified as well.

It's better than it was in the past, but I'm going to defer to Julian for the kinds of trouble you foresee coming.

Julian Zelizer: Yes. I think that legislation is an example of what Karen talked about. This is not a book purely of despair at all. I think each essay tries to find areas where reform has happened and it's improved our situation, either in the past, like the Voting Rights Act, or changes that come from the election reform law that passed in 2022, with bipartisan support, that does include tightening procedures within the states, which became such a problem.

It identifies the governor as the person who actually has to submit the certificates. It creates limitations on whether you can actually change who the electors are within the states. There's been improvements, but every system, even the one that came out of the 2022 reform, can be manipulated. Bad actors have a lot of room in American politics, especially within all our states.

There's just so many veto points, so to speak, that it's going to not just be legislation that creates a stronger system, but ongoing vigilance at the federal level and within the states, not just by politician, but movements and nonprofit organizations. We do have a better situation than we had in 2020, in part as a response to what we saw in states like Michigan, that there were efforts to really undermine what voters had decided.

Matt Katz: I want to ask you both one more question before I let you go. 90 some-odd days until the election, you spoke of the changes since the 2020 election just now, but what tests will the electoral system face this coming November? How will those tests be evidenced at the average polling station? What should we be looking for? Professor Greenberg, why don't we start with you?

Karen Greenberg: Well, I think the first thing we're going to be looking for on election day is the deterring of violence. Will people show up? How scared are they? How trained are our poll workers, because there's been such difficulty in getting people to hold the jobs, that have been poll workers before, and how much threats against poll workers will have deterred that? I think, actually, the feeling of, yes, you can vote.

We know what we're doing, as election workers, in helping you cast your vote. A sense of calm at the polls so that the authorities who are responsible for protecting the polls keep violence away from the polls themselves. I think those are two very important things about election day. I do think another thing to look for is something that you and Julian referred to in the past, is how the media covers this.

I'd love to see some primer classes on what to do and what not to do during election day so that that issue of violence and contestation is not fanned on that day. Just let the election happen. That's what I'll be looking for. Julian, over to you.

Julian Zelizer: The other thing gets back to the law, from what we have heard, certainly, Republicans were preparing for legal challenges after the voting takes place, or even while the voting takes place. I know there are a lot of more liberal organizations, like the ACLU, that are trying to prepare for that. I think we'll be watching to see how real that is. It's a compliment, in some ways, to the threat that Karen talked about, at the local level.

Then finally, obviously, in addition to the media violence and legal challenges to people's ability to vote and to the vote that they take, is what do our leaders do? Obviously, we're talking about one person in particular, the former president, now Republican nominee. How far does he go? Relevant to that is, does the party, his party, the Republican party, push back if he engages in the kind of denialism that has been really standard at this point, or does the party embrace that, should the vote not go his way, or even if the vote is going his way?

Those are, I think, the different pillars of what we should be looking for and thinking about.

Matt Katz: All right. We'll be looking. Julian Zelizer, Professor of History and Public Affairs at Princeton University, CNN Political Analyst, and NPR contributor, Karen Greenberg is director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law. Together, they're the editors of the new book, Our Nation at Risk: Election Integrity as a National Security Issue. Thank you both for writing this important work, and for being here on The Brian Lehrer Show.

Julian Zelizer: Thanks for having us.

Karen Greenberg: Thank you for having us. Yes.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.