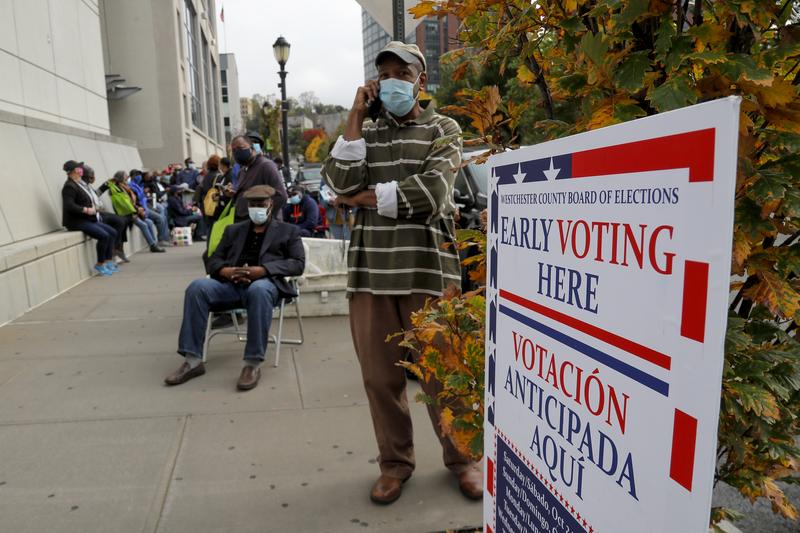

( Julie Jacobson / AP Photo )

Kelly McEvers, creator and host of NPR's Embedded podcast and Dan Girma, co-host and producer of Embedded, talk about their reporting (with The Marshall Project) on the police department in Yonkers, and its attempts at reform.

[music]

Matt Katz: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Welcome back everybody I'm Matt Katz reporter in the WNYC newsroom filling in for Brian today. Our next guests are the hosts and producer of the Great NPR Podcast Embedded. Producers that are partnered with the nonprofit newsroom, The Marshall Project over the last year or so. They took a look at how the Police Department in Yonkers tried to reform itself.

Joining us to talk about the show and Yonkers and the police are host Kelly McEvers and producer of Dan Girma, who just happens to be a former Brian Lehrer Show intern. Daniel, welcome back. Kelly, a pleasure to have you on WNYC.

Kelly McEvers: Hey, Matt. Thanks so much for having us.

Dan Girma: It's great to be back.

Matt Katz: Absolutely. Great. Excellent. Listeners, do you live in Yonkers? Have you had an experience with the police there in the past? Have things changed when it comes to police-community relations over the last 10 years or so? Yonkers or nearby residents give us a call, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Kelly, you've done a variety of shows on Embedded and you embed yourself in different communities and try to understand different issues from the inside out. Why did you want to look at police reform for this season and how did you end up in Yonkers?

Kelly McEvers: We've been obsessed with policing for a while. I think after a string of high-profile shootings of Black people by police over the last few years in what I loosely call the Black Lives Matter era starting from Ferguson onward we at the show just wanted to dig into policing at different times. We were really fascinated back in 2016 with how videos of these incidents affected conversation.

After George Floyd, I think we all decided that it was really important to dig back in and look at this. We decided to look at all the different ways that people were calling for the police to change. Obviously one of those ways is reform. It's not the only thing that people are calling for. We teamed up with The Marshall Project and they suggested that we go to Yonkers.

We were working with an investigative reporter named Simone Weichselbaum. She knew about Yonkers and sorry, I'm just hearing some people in the background I'm hoping they'll mute. It's hard for me to talk and listen at the same time.

Matt Katz: Is that on our end?

Kelly McEvers: Yes sorry. I could just hear it coming through, I'm hearing it currently.

Matt Katz: We'll try to figure out what that is. [laughs] Kelly, you're such a radio pro that we wanted to make things as difficult as possible for you.

Kelly McEvers: As difficult as possible. No, it's fine. Simone Weichselbaum suggested we go to Yonkers. The idea was Yonkers is a place that has been under oversight by the Department of Justice. This is a thing that happens to police departments around the country. You've probably heard about in Ferguson, Baltimore, Seattle, LA famously New Orleans, cities where police departments have a history of misconduct.

The DOJ will come in investigate and put those departments under different types of oversight. Yonkers is not in what's called the consent decree which is really common nowadays.

Common during the Obama administration but it is under an agreement with the DOJ. The idea is, look, there's a bunch of things that you need to do to reform. We wanted to look at that, but also Yonkers was headed by this charismatic police commissioner who had bought into the idea of reforming under the DOJ and was really pushing people to do it and was accessible to us. That just seemed like a good formula of things that we wanted to look at and see if reform was working and if so, how does it work?

Matt Katz: Got it. This police chief that you mentioned John Muller who was there until very recently. Dan, can you give us a sense of him and how he came to be a reformer?

Dan Girma: Funnily enough when the DOJ first came into Yonkers to look at the Police Department, John Muller was not very happy that they had come to town. He wasn't definitely the man he is today, but he started getting involved in a reform circle that exists within the policing community called PERF I'm blanking on the--

Kelly McEvers: Police Executive Research Forum.

Dan Girma: Police Executive Research Forum. Basically, a lot of high ranking officers that get advanced degrees in criminal justice and try and reimagine the way policing works and try and find ways to reform their practices. He got into this world of reform and it really started changing his opinion about police reform as a whole to the point where he ended up embracing what the DOJ was looking into and trying to change.

I think if I was going to describe he's a one-man show that really came in with a lot of energy a lot of zeal to try and opt the department into the reforms that the DOJ wanted to bring into Yonkers.

Matt Katz: How does he envision, let's say, for example, making officers less aggressive with people? What is his plan stated plan when it comes to that?

Dan Girma: I think he has a few things that he states in this plan. One is making sure that the police are having a positive relationship with the community. Another is this thing called position policing where they're trying to have a very pointed way of going about crime prevention. Also, this idea of procedural justice which is really the way that he would describe it is treating people with respect. When you are police officers, they don't feel that you're being antagonized.

Matt Katz: I want to actually play a clip from the first episode of Embedded for this season talks about procedural justice just to set it up for a second. The first woman's voice that will hear is Simone Weichselbaum. Kelly mentioned before she's formerly of The Marshall Project now of NBC news. She helped you report out this season. After that, we'll hear from Yonkers Police Chief Muller and they're talking about this concept of procedural justice. Here it goes.

Simone Weichselbaum: First, what is procedural justice? It's this idea that if you train cops to treat people fairly at a normal interaction a traffic stop, pedestrian stop, builds on that foundation. If there's a crime in your neighborhood, you're like, "Oh, that cop two weeks ago treated me fairly. I'm going to go help them solve that crime or be a witness in something," and one leads to another. However, what I found in Chicago that although they were taught these things, it wasn't digested so the cops on the street weren't necessarily doing it.

Matt Katz: Simone says people weren't helping cops solve crimes.

Simone Weichselbaum: The cops were complaining, well, they're not helping us solve it and then the community feels will they treat us like shit we're not going to help you and it's like the dog chasing its tail.

Dan Girma: I will agree but the Simone's point here the metrics--

Kelly McEvers: It's not about counting how many crimes people help you solve will Muller says.

John Muller: The whole point of procedural justice for me is just developing a better relationship with the community. If most people probably have a personal interaction with the police, less than five times in their entire life. We got to make all five of those count. For us, it has to do with what is the day-to-day interaction. It's those very minor.

Kelly McEvers: "What's your stat? What's your data point?" Simone asks.

John Muller: For what?

Simone: To measure, what are you measuring as successful?

John Muller: I haven't measured anything yet.

Matt Katz: What Simone wants is evidence. She wants Muller to show her the data that procedural justice works. Muller says Yale University researchers are working on this. They eventually surveyed more than 1,400 people in Yonkers to see how they feel about the cops.

Simone Weichselbaum: They found there was a high level of trust in the Yonkers police, but that trust was highest among white people and lowest among Black people.

Matt Katz: That was a clip from the latest season of Embedded. Kelly, what were your observations of the effect of procedural justice? Did you come away from reporting the season thinking that this was a meaningful method of reform or more of the same and that police-community relations will still be as fraught as always?

Kelly McEvers: That's such a complicated question. It's such a good question. When you dig in on policing and all of these different training programs that everyone has, each one of the programs has an acronym and a title and there's a bunch of people who go around and train cops and this stuff. Procedural justice is just one of the more recent ones. There's de-escalation training.

There's all kinds of these programs that cops can go through and so that's the big question. Is does it work? You sit in a couple of trainings for a couple of days over the course of a year and does it actually change how you do things? That's really hard. It's hard to quantify. You heard us talk about the Yale survey where they talk to people in the community about how they feel about the cops and look, I will say that we talk to a lot of people in Yonkers who feel like the cops are more respectful, that they have better sense of the community that they police.

That they have better connections with the community and John Muller will tell you, that's not just the job of the commissioner himself, but that it's all up and down. All up and down the ranks and the supervisors and the cops. Frankly, it's like a new batch of cops. They're younger and they listen to people when they talk about their concerns. All of that said, there's still a lot of people in the community who feel like the police could do a lot better job.

They can account for past in better ways. We can talk about that more. There's still this disconnect in the community because frankly, the police force does not look like the community it polices. It's still an overwhelmingly white police department and a city that's not very racially diverse. It's this one little training program isn't going to fix everything. We did see people on the street. We saw cops practicing de-escalation. Actually engaging with people in ways that seemed like there was more respect on the street. Now, was that just because we were there recording?

Matt Katz: Always hard to know.

Kelly McEvers: Exactly. This is the effects that we have.

Matt Katz: Let's hear from some folks in Yonkers. We have a caller from Yonkers and then any other residents of Yonkers who want to give us a buzz and tell us their experiences with the police there. The number is 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Let's go to Jonathan in Yonkers. Hey there, Jonathan, thanks for calling in.

Jonathan: Thank you for having me. Longtime listener glad I could contribute.

Matt Katz: Excellent.

Jonathan: I disagree with the speaker's comment about diversity of it. I'm finding that actually quite a different mix of people, men, women, different racial groups. I think it's not overwhelmingly white as I thought it would be when I got here. I do find the training excellent. Sorry, I just ran up the staircase, I left Greenwich Village for a three-story building here.

They're very good at de-escalating. They've had to de-escalate me because I'm constantly complaining about noise coming from a boombox, noise coming from the subway, commuter train station near my house. I can hear on a summer night. They have to calm me down when I'm yelling at them. I think they do a pretty good job of speaking to the people, making the noise, asking them to please move on.

I'm not sure if they give me as many tickets now. They just called me up last two weeks ago after I had an incident. The sergeant actually came to my house at this point to know who I am. Told me he issued a ticket and he was very nice and asked me if our things get any better. Do you find less noise? People can hang out on the street but they have to be respectful to the neighbors too.

Matt Katz: Have things gotten a little bit better. Do you think the police--

[crosstalk]

Jonathan: Actually, they seem to have cars patrolling once a problem starts they seem to put resources toward correcting it. Basically, it's just a car pulls up to the area, tells them you can't do this, turn it down. I think they're making an effort to make everyone happy.

Matt Katz: Thank you, Jonathan. I really appreciate you chiming in here. That's super helpful. It's so interesting, Kelly and Dan, how so much of what police work is involves stuff like this. It's not necessarily, chasing down bad guys down the block and high-speed car chases. It's these little quality of life issues that people call 911 about, that they call the police about. How officers handle such situations and avoid escalating such situations into something bigger is a huge part of what amounts to police-community relations.

Dan Girma: It is a huge part. I think one thing that we really got to learn, at least looking at Yonkers and the Yonkers Police is how much they have to do. In so many types of situations, they are really the only people available to call, whether it be a violent crime, whether it be a domestic dispute, whether it be a mental health crisis. There are some people ask the questions are do the police have to do too much in that regard?

Are they being stretched too thin because they have so much on their plate? Which is, I think, a fair question to ask and might be something that cops have to ask themselves too.

Kelly McEvers: It's a big question across the country right now. There's studies have shown that what is it, around 3% or 4% of all calls that come in, only that low number actually involve violence. Then you get into the questions of like, "Do you need a cop in a situation like that?"

We look into that in one of our episode actually, that's coming out tomorrow. I think John Muller when he talks about this too when he talks about procedural justice, some of the things that he's, learned from these police conferences and conversations that are happening at the national level is like-- he tells this to his cops, we're in the business of customer service.

We're not supposed to be in the business of being antagonistic with the people that we serve. People are calling us and asking us for help with something. We need to show up and we need to be just polite and transparent. That's all the procedural justice is about just narrating the situation and saying, "Here's why I've pulled you over. Here's what I'm going to do next. Here's what I expect of you. Do you have any questions for me?" Simple stuff but stuff that I think most of us know doesn't always necessarily happen when you have an interaction with a police officer.

Matt Katz: You referenced the episode that comes out tomorrow. I want to play a clip from that. First, I got to do a little business. I'm Matt Katz from the WNYC newsroom, filling in for Brian Lehrer. This is WNYC FM HD and AM New York, WNJT FM 88.1 Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcong, and WNGO 90.3 Toms River. This is New York and New Jersey, Public Radio. I want to play a clip from episode four of Embedded. This involves Chief Muller, who we've been talking about, and he comes across a situation and you guys are there with your microphones.

Simone Weichselbaum: As we start walking, I have to ask Muller a question that a lot of people are asking right. That woman, what does she mean? In that moment when you say, you call the cops. You are the cops that you to call in the cop. She look like she need a cop?

John Muller: The question is, who else do we call? She's passed out on the sidewalk as far as what I saw when we walked by. Did you watch that? We don't know if she's sleeping.

Simone Weichselbaum: Is she going to be afraid of a cop?

John Muller: No.

Simone Weichselbaum: If they show up?

John Muller: Not our cops, not at all.

Simone Weichselbaum: That's the kind of situation we're having. Some people would say call social services.

John Muller: What is the dispatch number? Is someone available to go? When you say call, who do we call? What is their response time? Who is it?

Simone Weichselbaum: It's like the argument thing is like you guys are just faster and more available.

John Muller: No, what I say is where the default, whether we should be or not. It was through no design of our own that, until you can design something as responsive and as rapid as the police for those type of situations, you're going to have to call us.

Kelly McEvers: Then Muller changes the subject.

Matt Katz: Kelly, here, the context is that you're with Muller there's a woman sleeping on the street. He calls an officer to get help. Then you go back and forth a little bit like why are police involved in this kind of thing? There's other scenes from the season like a woman who's clearly in mental distress and the cops who are not trained mental health workers, they're forced to try to de-escalate the situation. Did you run up against that a lot that you're like, "Maybe the traditional police response is not necessarily appropriate for all the reasons why we call 911?"

Kelly McEvers: This is something so many people are talking about right now in policing circles. You've reported on it. I know there's a couple of pilot programs in New York City or there's a couple of neighborhoods that have this pilot program in New York City. It's called Be Heard. The idea is to divert 911 calls right at the dispatcher moment. When somebody answers that phone calls to figure out, is this a situation that involves a weapon?

Is this a potentially really violent situation or is this something that doesn't need a cop? For those programs in New York City, they've got, social workers hired to be on call when it isn't necessarily a cop.

That call's going to the EMT is basically at a fire station and an EMT and a social worker, unarmed, are going to go and respond to that situation. One of the interesting things about it, and we spent a little time we spent a couple of hours with them up in the Bronx one afternoon when they were doing their work. Is that, they told me, was the great thing about their job and the way they do it is they can take time.

They're not in a hurry. Somebody having a mental health crisis. They don't need to just figure something out and get it resolved. They can just stand there and talk to somebody. We know, a Washington Post analysis found that one in four police shootings involve somebody who's having some mental health crisis. There's definitely an outcry right now for people saying this is we need some different solution. Roughly 20 cities around the country are trying programs like this, Denver, Albuquerque, LA, Oakland, like I said this program in New York City, Westchester county, where Yonkers is, they've started one too.

It's a little bit different, there's not full-time social workers set aside to answer these calls, but what they are working on is diverting those 911 calls, either to someone on the phone who can help the person who's in mental health crisis or folks on the ground who can respond. The thing that's different is they're probably likely to respond with the police most of the time, and that's really the thing. If you look at these programs, is it a full civilian response or are the cops going to come to?

For someone like Sheron Atwell, this woman that you mentioned till we met in our series, this is someone who has mental illness. She was arrested 36 times by the Yonkers cops, from 2016 until now. The cops themselves acknowledge that this is not the thing for her. They want to help her. They tried to help her, but like you said, they're not equipped to help her. It's not like you could, and Muller's right, you can't just flip some switch and automatically just have a bunch of people who are there to help her instead of the cops.

This is an incredibly important question right now in policing. It's good to see some of these programs up and working. There's some decent data about how they do work and they do cost to this less money in the end.

Matt Katz: You mentioned Muller, Dan, where is Chief Muller? The main character in your season here up and left. Tell us what he's up to because it's very interesting to our listeners.

Kelly McEvers: Oh yes.

Dan Girma: Over the course of our reporting quite abruptly, John Muller left the Yonkers Police Department to join the MTA, the Metropolitan Transit Authority Police to head them up. It posed a new question, which is also an important question which is the staying power of a reform when someone who had been the champion of reform leaves. A lot of times you have issues where an individual becomes the face of a type of movement.

It really is the driving force behind a certain type of change and you obviously hope that change can persist and that they've planted the roots of change within a department or whatever organization they're in but people have questions about whether things are going to keep getting better or if they're going to stay the same or if they may revert back to a way things were that people don't want.

Kelly McEvers: The DOJ is still monitoring Yonkers, they're still under this agreement.

Matt Katz: Right. That goes back to 2007.

Kelly McEvers: It goes all the way back to 2007 but they entered into the actual agreement in 2016. The DOJ was technically investigating Yonkers for all those years, and since 2016 they've been in this agreement where they basically said, "We're going to sign on the dotted line and we're going to make all of these changes." It's this long list of changes. A lot of it is reporting and people say, "Oh, it's paperwork," but it actually is the kind of stuff that can make a difference in a department.

How do you report a use of force, how do you write that down? How do you characterize it? Then how does that officer then get tracked over time? Is there a way to look at an officer who's got several times that they've used force against a person in the community, should there be a red flag that goes up and says, "Huh, we got to look out for this person. We got to discipline this person. We got to spend more time investigating complaints made by people from the community."

Those are the kinds of changes that are on that list and that are still being required of Yonkers. As Muller will say, "It's not just a one-man band." There are people up and down the system who have gotten on board with doing things in a different way, and he'll be the first to tell you that, "Just because he's gone, doesn't mean they're going to stop." We ran down a whole list of stuff with him. Is this program going to continue? Is this program going to continue?

Is this one, is this one, and the answer is yes. A lot of the stuff that was put in place during these reform years are going to continue. The big question for us, and one of the things we spent a bunch of time on in our second episode is looking into allegations of misconduct in the past. I feel like if you scratch the surface of any police department of the 18,000 plus police departments in this country, you're going to find some stuff.

Matt Katz: Sure.

Kelly McEvers: Yonkers has a pretty particular history of wrongdoing. It's why the DOJ came in in the first place. There's still a lot of people in this community who feel like that past has not been answered for. There's still a lot of officers who either stayed on the job or were promoted or were allowed to retire with their pensions, who people in the community know have been accused of multiple incidents of wrongdoing.

We looked into that too, and that's just this unresolved thing in this community and in a lot of communities, obviously in New York City and beyond. We really tried to look hard at how you deal with that too and there's no great, perfect answer there either.

Matt Katz: Before I let you guys go, I want to take one more call from Yonkers. John. Hey John, are you there?

John: Yes. Hi.

Matt Katz: Hi. Thanks for calling in.

John: Yes. Can you hear me?

Matt Katz: Yes, absolutely.

John: Hi. I was a member of one of the organizers of a group of concerned downtown residents and stakeholders called the Yonkers Downtown community for the waterfront and--

Kelly McEvers: Oh yes. John, we met you.

Dan Girma: Yes.

John: You guys are [unintelligible 00:25:42]. That's right. I remember that. I'm just calling because I'm concerned that it sounds like there's a little bit of an entrance here, but all of this being laid at the feet of John Muller when he was under the confines of what lawmakers in the Courts in City Hall. Collectively, we thought that Muller was doing an amazing job of trying to deal with all of these constraints and that he was always available to us, the meeting that we had at Paxos was a regular thing.

We also had Town Hall meetings and we had 75 to 95 people come at Philipse Manor Hall State, Muller instigated that he gave everybody his cell phone, you could contact him anytime and that was a diversified amount of people. There were Black Latinos and it was the kind of meeting where the Mayor came a few times. We had commissioners come, and Muller, he was the heartbeat of all that with this communication with the neighborhood.

I just feel like he needs a little bit of a positive spin on the job that he did here. Again, we are actually dismayed that he left. We wish the new commissioner all the best and we wish John Muller really all the good luck that he's going to need when he is working with the MTA but he is somebody that we really regret he is not going to be here anymore. We felt very happy that he was in charge.

Kelly McEvers: It's such a good point and it's something you see in police departments all over the country. For different reasons, commissioners who come in and do a good job, they move on and they do other things. That has you asking questions in places, like Houston or New Orleans or Baltimore or Philly or anywhere, what happens when the personality, that person who's so committed, to having a relationship with the community? Like you said, John, we heard this from so many people I can't even tell you. Everybody heard that guys.

Dan Girma: We were driving around with John Muller, and people are recognizing him from his car and saying, "Hello." That's the impact he had in the Yonkers community. It was very clear.

Kelly McEvers: Yes, it's a good point that you make, not everybody's going to be that personable person, that's fine. You can't expect everybody to be the same way but when that drive, that commitment is gone or moves on, what does it mean for reform efforts?

Matt Katz: After lauding the chief here I should note that we have a Twitter user who chimed in and said, "Why is Brian Lehrer--" Meaning The Brian Lehrer Show on, I'm filling in for him, "Why is the Brian Lehrer show engaging in propaganda, this morning, police propaganda?" We haven't talked about it a lot, but I will say that reporter Simone Weichselbaum dug into police misconduct for this series, really disturbing scenarios involving police abuse.

You also had my former colleague WNYC reporter George Joseph, a former WNYC reporter who's investigated police abuse and next door, Mount Vernon. He's on this season. This isn't a simple story of a hero police chief who comes in and then the community loves the police department. It's a lot more nuance and complicated than that, this season, of Embedded, right?

Kelly McEvers: Yes, in our second episode, we spent an entire episode and basically the greater part of a year, looking into the misconduct of the Yonkers Police. You can't just walk in and everybody says, "Look, we're doing a great job. We're reforming," when multiple people in the community, we didn't just pull this out of our own hats. It was multiple people in the community saying, "Look, I was wronged by the police. I feel that I have not gotten justice. I have filed complaints. I have sought reprieve and I have not gotten that."

We had to hear those people out and we had to look into their concerns. I will tell you that what we found was some patterns of wrongdoing that have never been talked about on the record before. In particular, falsifying warrants, people who went to jail for years at a time wrongfully in several cases. That was just barely from barely, barely, barely scratching the surface. We looked into two officers who were, had been convicted and fired from the force.

As I like to say, these guys were already the low-hanging fruit. We went to the da of Westchester county and put it to her and asked her what she was gonna do about it. She's looking into the allegations. I just want people listening to know that is definitely part of any conversation when you're talking about the police, you got to look into it. Again, I think the cops would say, or you're just trying to find something bad to say, because you're the media it's like, no, this is what we were hearing from people in the community.

This is what this is. These are the questions they're still asking. They're saying it publicly. They're not just saying it to journalists. They're saying it at public forums after George Floyd at protests, these are people who are known to the com known to the cops and who feel like they want justice.

Matt Katz: It's a great season listeners get embedded wherever you get your pods. My guests have been NPR's Kelly McEvers and Dan Girma from the Embedded podcast. Kelly, Dan, thanks so much for this conversation and for joining us really appreciate it.

Dan Girma: Thank you so much.

Kelly McEvers: Thanks so much, Matt.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.