I've lived in Harlem since 2009. When I was looking at apartments, I had Senegalese food with my then-girlfriend and it felt like home — it was similar to the Ghanaian cuisine my dad cooked when I was growing up in Trinidad. When I moved to Central Harlem, there was no "Restaurant Row" on Frederick Douglass Boulevard; mostly it was vacated storefronts. But now high-end eateries like Vinateria and luxury condos line the wide sidewalks, an indication of the gentrification and new diversity of the neighborhood.

I met Justin Clavadetscher after he moved into an apartment where I used to live. He's a white New Jersey native who has lived in Central Harlem for about two years. He told me that he's thought about getting his hair cut in one of the local barbershops, but he felt intimidated.

“I can't even count on my fingers and toes how many times I left my apartment to get my hair cut and came back without a haircut,” Justin said. “Even 10 times where I literally had my hand on the door, but something just got kicked up, and I bailed at the last second. I’m like, ‘Dude you need a haircut, just walk in the door.' It’s a fear of the unknown. You need to have a more personal interaction with the barber; it’s like a social club.”

He's not wrong. Barbershops are a local hangout in most historically black neighborhoods. Men come to talk about sports, politics — and get their hair cut. I had never seen a white guy at my barbershop before.

But I knew he'd be welcome. So I took him to the AK Barbershop on 116th Street, near St. Nicholas Avenue, and introduced him to my barber Jesse Johnson. I assured him Jesse could execute what Justin calls the “Boardwalk Empire” look, trimming the sides of his head short and keeping his straight, black hair long at the top.

It’s the same reason Lindsay Lowe, my former grad school colleague, hasn’t had her long curly hair styled at a local salon, even though she’s lived in Central Harlem for four years. “I know hairdressers are trained on all textures of hair, so I think it’s less of a skill thing; I think it’s more of a social barrier,” said Lindsay.

But why is there this social barrier? Vassar College professor Quincy Mills thinks it's because white people worry about being outsiders. But they shouldn't be concerned, he said.

“There’s a way in which African Americans who have congregated in certain spaces have generally been very welcoming for whites to enter that space, certainly in the context of the black church," said Mills, who's the author of Cutting Along the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America. "As an African American male, it’s actually rare that I’m not in a predominantly white space, and so I don’t have a choice to sort of think about whether I’m going to be in a space that’s majority white. So I think it’s interesting that a white person would sort of be hesitant, but also be able to make that choice to not enter a space where they are the only white person.”

Barbershops and salons in Central Harlem are intimate environments where blacks have congregated for decades. In the 1940s through the 1960s, black barbershops became places where African Americans met to organize protest campaigns and discuss racial politics, and they remain neighborhood institutions in many black communities. That's why white people like Justin and Lindsay may be perfectly comfortable socializing in bars and restaurants in Harlem, but worried about the specific social dynamics of a barbershop or salon.

“When you’re at a bar, you might sit at the bar or at a table, but you‘re not engaging with the entire bar,” Mills said. “The bar is usually big enough that you know the entire bar is not having one big conversation or debate. Many barber shops or most barbershops are actually small, you sort of think about a two- or three-chair shop, and so you can sit anywhere in the shop and have a conversation with someone else on the other side of the shop.”

That social aspect is part of what I like about black barbershops. Getting caught in the crossfire of conversation is inevitable. But many white people might have complicated relationships with the black issues — police brutality, gentrification — that are the topic of the day. Octavio Moore discovered just that at his shop for women, Salon 2266, on Frederick Douglass Boulevard.

“There was a client that wasn’t a client of mine and just an organic conversation about real estate in Harlem or in Manhattan, and one of the clients proceeded to say, 'Well you know how the white man, how they own'...so, I went to the lady and said, ‘Don’t forget girl, there’s a Caucasian lady over on the couch,’” Octavio said.

But Justin seemed pretty relaxed in the middle of the basketball banter during his hair cut at the AK Barbershop. “I've always been interested in black culture: athletes, comedians, films,” he said. “I always wanted to be the white guy who could cross over into that culture. I think a lot of this is wanting to be accepted into black culture. It's one of these things when it was in theory it made sense, but when it came time to do it, things changed.”

The black community in Central Harlem is large enough to keep the local barbershops and salons afloat, but hair professionals know customers come and go and they're always looking for new clients. So they're trying to become more welcoming to the new, non-black residents of the neighborhood.

Octavio and barber Polo Greene both forbid customers and staff to use obscene language, especially the N-word, and Octavio prefers the sounds of Erykah Badu than that of Nicki Minaj, during work hours. Their employees are all middle-aged black men and women, but Octavio and Polo are actively seeking to add some diversity to their staffs.

“They only see a bunch of black faces in here; if I had a Puerto Rican or a white boy, it would change their vision,” Polo said. “If a white boy came in here with a license, I would hire him on the spot.”

Polo hopes there are more white people like Justin in Harlem, people willing to break the social barrier and enter his shop, Harlem Masters Barbershop (he is currently relocating). He said they would find his staff and clients to be friendly and welcoming. They may even enjoy the social scene, as Justin did at AK.

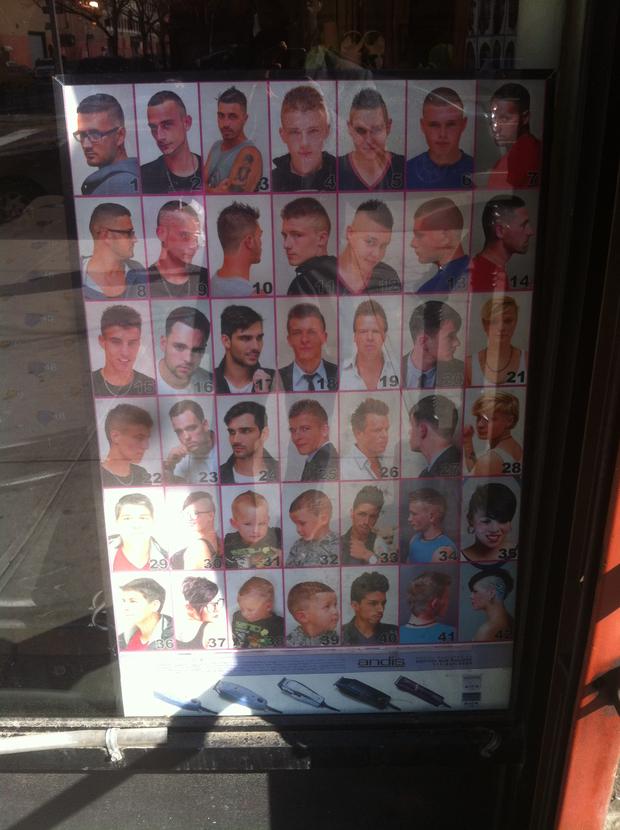

But five years ago, Polo placed a sign featuring white models sporting popular hairstyles in his storefront window. So far, it has gained him very few clients.

“We got white guys who come in and we talk, but it’s just that there aren't enough of them like that, that come in and socialize," Polo said. “Black people aren't going anywhere. Black people are here. So they come in all the time. White people don't come in all the time, because they think that your conversation isn't about what their conversation is about.”

When Justin left the AK Barbershop, Jesse said he hoped it would be a turning point. Maybe Justin would tell his friends, and they would tell their friends, and enough white men would start coming in, to the point that strangers would feel comfortable dropping by. But, he said, he doubts it will happen. Barbershops have always been segregated and he expects that to continue.

But toward the end of his haircut, Justin told Jesse, "I made the assumption that coming in would mess things up for you guys and make you uncomfortable, and I was wrong about that." Justin told me afterward that he would probably be back.