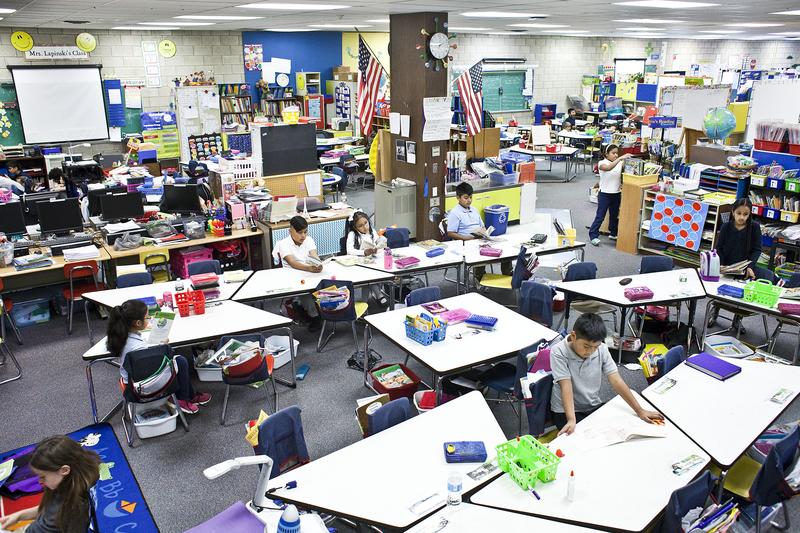

At a Freehold, N.J., elementary school, more than 500 students share a vast, open space where bookshelves, whiteboards, storage cubbies and other pieces of furniture are the only boundaries between classrooms.

There are no walls because the building was originally designed in the 1970s to be a smaller Montessori school, Superintendent Rocco Tomazic explained during a recent tour. But now, it’s noisy and crowded, and the district doesn't have the money to move each of the classes into traditional closed classrooms — the kind with walls, and a lot fewer distractions.

The issue for Freehold Borough — and an estimated two-thirds of New Jersey's 586 school districts — is the state's nine-year-old formula for paying for public schools. Adopted by the state legislature in 2008, it calculates how much each district needs to spend to ensure that students receive New Jersey's promise of a "thorough and efficient" education," regardless of income.

The formula directs extra dollars to districts with children who are learning English, kids with disabilities and those living in poverty. But towns like Freehold Borough, where half of the school children are Latino, have not gotten their full share of funding under the formula since 2010. This year, for instance, the district was due $23 million, Tomazic said. It got $9 million.

"State aid has been flat-funded since at least 2010, with no adjustments for enrollment, for our at-risk students, for our special-needs students, for our English-language-learner students," said Joe Howe, the district's business administrator.

When the state falls short, the burden falls on local property owners. In Freehold, that has meant noisy, overcrowded classes, the library converted into classrooms for English learners, the small gymnasium that doubles as the school cafeteria, and the elementary school class with 28 students – well over the recommended 21.

Freehold Borough School District is the 33rd poorest district in New Jersey, with 78 percent of students eligible for subsidized meals. Low-income communities cannot turn to property taxpayers to generate the money the state has shorted them because the tax base won't generate enough money.

David Sciarra, director of the New Jersey Education Law Center, says the problem isn’t the funding formula, it’s the governor’s decision not to abide by it.

"The problem is, seven, going on eight years of Governor Christie's stubborn refusal to put any new state aid to invest any new money over an extended period of time," Sciarra said.

At an April hearing in Trenton Assemblyman Lou Greenwald – a Democrat from Voorhees Township in South Jersey - said as many as 550 school districts are getting less than 100 percent of what the state's own formula says they're owed.

Meanwhile, some districts in the state are overfunded. Places like Jersey City, Hoboken and Asbury Park — cities that have gentrified in the last decade — are actually getting more money than they're owed from the state. A loophole in the formula allows those cities to continuing getting the same aid even after the student population has shrunk or property tax revenues increase.

In his February budget address, Gov. Christie demanded that legislators fix the formula. But a solution would pit district against district, and the needs of property owners against the needs of public school students.

Emotions are rising. Students staged a walkout in Clifton. In Paterson, one of the state's poorest cities, hundreds of teachers have been laid off.

When state legislators recently held a budget hearing in Bergen County, parents and district administrators packed the room to plead for more funding. Valerie Freeman, a parent in Paterson, said nurses and substance abuse counselors have been cut throughout the district.

"Most of our children, they walk through harsh areas in our school. Most of them are coming to school high. But, what can the teacher do?" she asked. "The teachers can't do anything about it."

Despite Christie’s demands that legislators work with his office on a new funding mechanism, the issue of how to get enough money to school districts will likely fall on the next governor. And it’s a monumental task because it is one of many financial issues the state’s leaders are wrestling with. Others include funding a transportation system that has had several high-profile breakdowns, and funding the state’s pension system.

The four leading Democratic candidates all say the state has an obligation to fund the existing school funding formula.

State Assemblyman John Wisniewski said he would find the money to fund schools by limiting the amount of tax breaks given to corporations. He criticized the Christie Administration for allowing millions in tax breaks to go to companies, while schools struggle.

State Assemblymen Ray Lesniak, also a Democrat, said he wants to fully fund schools, and said he would put a moratorium on charter schools; public schools lose money when student’s leave to attend public charter schools because the state money is shifted to the charter.

Jim Johnson, a former federal prosecutor, said he would fund the formula and expand it to include pre-kindergarten and after-school services. He said he would go after federal dollars to support the programs.

Former Goldman Sachs executive Phil Murphy say the state has an obligation to fund the formula for students, though he said it may need to be tweaked. He also said it will be necessary to raise taxes.

Lt. Governor Kim Guadagno, who is seeking to replace her boss, says the formula needs to be overhauled, but she also says the extra money that has gone to over-funded districts should be directed to property taxpayers.

Her opponent, Republican Jack Ciattarelli, a state assemblyman from Somerville, has a detailed plan that includes requiring all communities to contribute at least 25 percent of the public education costs, and reducing the excess aid some districts are getting by 20 percent a year over five years.

State Senate President Stephen Sweeney, a Democrat from West Deptford who is not running for governor, wants to shift the excess aid from overfunded districts — his office estimates it to be about $540 million — to underfunded schools. His plan would also gradually increase funding by $100 million over five years to bring all districts up to 100 percent of what the state formula says they need to educate their students; it would rely on state revenues for that money.

But there is push back from those districts that have gotten the extra money. Their property owners don't want to see their taxes go up, either.

In Freehold Borough, Superintendent Tomazic will get some relief in about two years. Last year, the state's Schools Development Authority agreed to fund some capital projects in the district — renovations that will restore libraries and provide some new classroom space. The district had appealed to the authority after local voters rejected two referendums to fund the capital improvements. Tomazic had argued he couldn't give his kids the "thorough and efficient" education the state's law promised them.

"We cited regulations and law of what we were supposed to do and showed where were short because of the space," like shutting down his libraries and cutting gym time. And he tracked how district kids performed after they went to a regional high school.

"Our students were not faring very well in getting into the honors when compared to the seven sending districts, all of which were wealthy," Tomazic said.

But when the renovations are done in late 2018, the district will still have 200 more students than its schools were designed to hold, and the Learning Center elementary school will still have classrooms without walls, he said.

Building new classrooms does not solve all Freehold’s problems. Unless the state fulfills what the funding formula calls for, Tomazic says, he can't promise he'll have teachers to fill them.