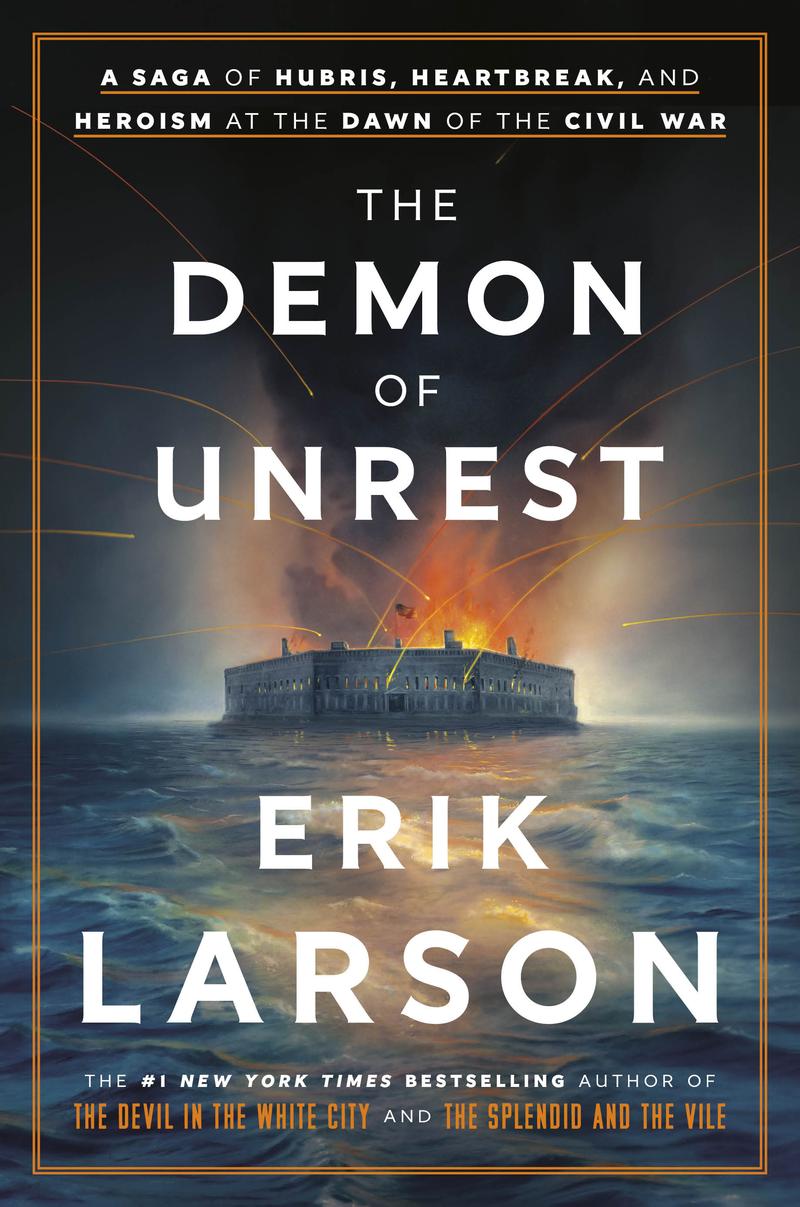

( Courtesy of Crown Publishing Group )

Get Lit is back! We kick off our fall season with best-selling author and historian Erik Larson. He joined us for a live, in-person event to discuss his latest history of the Civil War, The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War.

Title: Get Lit Returns! With Erik Larson [theme music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Bestselling author and historian Erik Larson decided long ago that he would never write a book about the Civil War. That all changed in the wake of January 6, when he saw the parallels between our own election crisis and the unrest the country experienced in the lead-up to Abraham Lincoln's inauguration. He couldn't ignore the call to write about this turbulent period. The book is titled The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War.

It vividly recounts the tense days between the election of Abraham Lincoln and the firing on Fort Sumter that marked the beginning of the Civil War. Throughout the book, Erik Larson brings these historical figures to life, from Lincoln to President James Buchanan, to a Confederate diarist named Mary Chesnut, to a staunch secessionist named Edmund Ruffin. He also makes the case that there is no doubt that slavery was the true issue at the center of the war, not states rights.

We were thrilled that Erik Larson was our September Get Lit with All Of It book club author. He joined us on Monday for a sold-out event at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library. I began our conversation by asking Erik Larson how he decided to write about this particular period of history.

Erik Larson: The reason this came about, first of all, I am on record as having said numerous times, you can google this, that I would never, ever write about the Civil War and that I would never write about Abraham Lincoln. Came the pandemic, I was in the midst of a tour from my previous book, The Splendid and the Vile. It was cut short, cut in half by the pandemic. Lockdown March 12, my wife's birthday. I'm on my way home.

Alison Stewart: Oh boy.

Erik Larson: At least I was home for her birthday. Find myself with a lot more time on my hands than I had expected to have and I started thinking about ideas for what would be my next project. As you recall, there was a good deal of political discord then as now, and people were actually talking about secession and a modern Civil War at the time, as they are rather foolishly today. I just found myself thinking, "Well, how did the Civil War actually get started?" I had only a high school timeline perception of the Civil War.

I've read some books about it, but I'm not a Civil War buff, never was. I just thought, "Mm, how did that start?" That's often how I leap into one of my books. It's just a question. Now, my ordinary MO would have been to jump into an archive without even telling the archivist that I was going to come and just see what kind of material was available. I couldn't do it. Pandemic didn't want to do it. Even if the archives had been open, I would not want to have gone there.

I found this set of documents online, and [unintelligible 00:03:03] got a bound volume of it called The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. How's that for a recollection? I started reading this thing and it just was so suspenseful. This is hundreds of documents in scrupulous chronological order, telegram, response, letter, response, response, response, chronicling this ascent or descent, if I want to look at it, intention and suspense toward the start of the Civil War.

I thought, "Wow, gosh, my job is half done because of this." I started thinking about it in a more serious way, but I was still wandering in the wilderness, looking for the next idea until January 6, 2021. Sitting in my office, watching this thing unfold, feeling that rush of emotions that I'm sure we all felt, anxiety, fear, anger, and so forth, and realizing that back in 1861, this is what people must have been feeling in America on both sides of the Mason Dixon line. If I could somehow try to capture that power of that moment, maybe this would be a very worthy thing to do. It was a story for our time, not just something from the past. Now, that's a longer answer than you wanted.

Alison Stewart: That was a great answer. Have you been to Fort Sumter?

Erik Larson: Yes, I've been to Fort Sumter.

Alison Stewart: How did it change for you after writing this book?

Erik Larson: I have to say that Fort Sumter was a very disappointing experience because the Union destroyed Fort Sumter in 1863 in a prolonged bombardment that basically turned it into a pile of pulverized brick. There has not been that much that was done to try to bring it back to what it was in '18, '60, '61, which was a 50-foot-tall sea fortress with three tiers of guns. Now, it's basically one tier of fairly modern weapons because of a World War II fortress and so forth.

What it did do for me was that standing there on the one promontory within the fort, I was able to get a sense of how close the opposing artillery was by the time of the Sumter bombardment. These guys in this fort, 75 men plus their commander, Major Robert Anderson, these guys were surrounded by heavy artillery, manned by people who had one thought in mind when this bombardment began, which was to kill Major Anderson and his men. They had no food. They had no prospect of supplies, and there they were.

Alison Stewart: As you said, you were motivated by January 6, what events surrounding Lincoln's election and our inauguration. What did it reveal to you about the vulnerabilities of our electoral system?

Erik Larson: What was so interesting to me was that the two moments of gravest national concern in 1861, before the Civil War actually started, were, would the electoral count come off as planned and as the constitution requires? Would the new president, Abraham Lincoln, would he actually be inaugurated, or would something awful happen before he got to that point? The electoral count was really interesting because they handled it very differently back in 1861. I say they, this is due to General Winfield Scott, who was America's commanding general back in this period.

This guy was six foot four. He weighed about 350 pounds. He had every conceivable ailment that somebody could have. He barely had legs. He was on his last legs, and he kept his feet in an ice bath day after day, but this man was absolutely loyal to the United States of America. He vowed that this electoral count was going to happen come hell or high water.

He filled Washington troops with cavalry with cannon, and he made the specific vow that if anybody tried to disrupt the electoral count, he was going to strap that person to the front of a cannon and blow him into the hills of Arlington, Virginia. The term he used was, "I will manure the hills of Arlington, Virginia, with his body." The electoral count came off. It was surprise, surprise, although there was an attempt by disgruntled southern-leaning people to try to get into the Capitol, but they were repelled readily because of this armed force.

Alison Stewart: You've written about such giants. Winston Churchill, Lincoln. How do you write about these giants and make them seem real?

Erik Larson: Yes, this goes back to Churchill, when I did my book, The Splendid and the Vile about Churchill and the Blitz. I sat down for breakfast with the head of the International Churchill Society, and it was basically all he could do to keep from asking me, "What the hell do you think you're doing? Here you are, just coming out of the blue, trying to write about Churchill." I said to him, as I said more recently to someone down in Charleston about the Civil War.

I said, "Well, it's all in the telling." It's all how you tell a story and if you tell it right, people will suspend what they know, what they think they know about a particular event and will allow themselves to fall back into time and get caught up in the story." That was my take. Having said that, I would say that I probably should have stuck to my vow never to write about the Civil War, and I will never write about it again.

Alison Stewart: What do you understand about Lincoln as a person after writing this?

Erik Larson: Lincoln, I'm sufficiently arrogant that I decided, "Okay, yes, there's this whole hagiography of Lincoln. Everybody loves, loves Lincoln, and that always brings out the contrary in me. My attitude with this book was, "All right, prove it to me. Show me what you got." He did. He did. I really came to love Abraham Lincoln in a way that I have not loved other characters because of his humanity, his warmth, his integrity, the quality of his thought.

I don't know that there was an unoriginal phrase that he wrote in his correspondence or in his speeches, but what especially endeared me to Lincoln were two things. One, he couldn't spell. He could not spell the word inauguration. He could not spell the word inauguration, and he could not spell Fort Sumter. He kept adding a P, Sumpter. There is no P in Sumter. The other thing that really endeared me to him was that he and Mary Todd before they set out from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington for the inauguration, they had a yard sale. They did.

They had a yard sale. I have the receipt. They had a yard sale and because they wanted to sell a lot of their goods so that they could actually help pay for this trip from Springfield to Washington so he could be inaugurated as president of the United States. I fell for him.

Alison Stewart: Why did you add that detail about him not being a good speller?

Erik Larson: Oh, my God. How could I not? See, this is probably a flaw in how I think about things, but it actually cuts to why I don't use researchers when I do my research because I'm looking for these things. If I go into an archive, this may sound strange, but I don't know what I'm looking for until I find it, until I see it and I recognize it. As soon as I came across that yard sale, I was like, "Okay, this is going to the book. Sure. Sure it is." The same thing about the misspellings and so forth.

Alison Stewart: It seems pretty clear that Lincoln did not set out to abolish slavery.

Erik Larson: Right. It's clear to us.

Alison Stewart: Clear to us, yes. Why did so many Southerners believe that he was going to do it?

Erik Larson: We talk about echo chambers today. This is another similarity in the past to the present. Lincoln was very clear in the run-up to his inauguration that he had no intention of abolishing slavery, that he would respect slavery in those states where it existed. He even went so far as to say that he would support the Fugitive Slave Act, which was anathema to Northern abolitionists. The Fugitive Slave Act was essentially allowed planters to come north with impunity, to seize escaped slaves and bring them back down to the South.

Lincoln made it very clear that these were his views. He was very frustrated that people in the South did not get it. In the South, Southerners, the prevailing view was that Lincoln was essentially the Antichrist, that he had one goal, and that one goal was to abolish slavery. Now, what Lincoln did not really grasp initially was that for Southerners, the abolition of slavery would have been an existential disaster. The entire capital structure of the South was based on the enslavement of Black human beings.

Lincoln did not really get that this was this absolutely existential thing for the Southerners. They went off into their own little world deciding, "Okay, all he wants to do is abolish slavery. That's all he wants to do." Despite Lincoln's protestations to the contract, that's how they felt.

Alison Stewart: It was interesting, your description of Southerners because you used the words chivalry and loyalty. Chivalry and loyalty. What did loyalty mean to a Southerner?

Erik Larson: Loyalty certainly didn't mean anything with regard to loyalty to the United States. Chivalry was the interesting thing to me. Southern planters believed themselves to be this exalted, almost knights of the Round Table crowd. They literally referred to themselves as the chivalry, the chivalry with a heightened sense of hospitality and manners and so forth, and acting almost this part. When I first read one planter referring to himself and his friends as the chivalry, I thought this must be an aberration, but it was not.

They refer to themselves as a chivalry, so much so that they held what were called rings tournaments, where Southerners, southern planters, their sons, themselves, they would dress up as their favorite knight from medieval era, get on a horse, and with a lance, they didn't do this to each other. They didn't want to kill each other, but they would race down a course, spearing rings hanging from above the course, this being a demonstration of their horsemanship. The ability to pierce these rings.

If it was a rings and heads tournament, then at the very end of the course, there was an inanimate figure. They would draw out their saber and hack this thing to bits. This is the chivalry. This is how they believed. Not everybody, of course, but a certain subset.

Alison Stewart: How did the idea of chivalry fit in with slavery?

Erik Larson: That's a good question, but they worked that out for themselves. No, seriously. She raises a very important point there. There was, starting around 1800, even planters in South Carolina and the slave-owning states felt that slavery was what they were referred to as a necessary evil. As the world advanced, as Britain led the way in the abolition of slavery, and the North became more and more energetically abolitionist, in the South, the attitude changed because they owned enslaved people.

These were people who gave them their livelihood and their culture. If that was a bad thing, then they were bad. There arose something called the pro-slavery movement, which is a very powerful movement in the 1800s in the antebellum period, where Southerners, white southern planters, and others managed to convince themselves that slavery was the best of all possible worlds for themselves, but also for the enslaved Blacks, because, look, three meals a day, they were not subject to vicissitudes of the economy.

Literally, what's to complain? Never mind that one planter, who's one of my favorite villains in the book, has in his manual for his overseers. He ends it with a segment on, very precisely, detailing how to whip an enslaved Black slave.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about Mary Chesnut. You really were taken with her diary. She was the wife of James Chesnut, a Confederate politician and a soldier. What insights did she provide for you?

Erik Larson: Mary Chesnut was this really terrific, terrific diarist. Her voice as a writer was very contemporary. If somebody were to read an excerpt of Mary Chesnut's actual diary. There are a number of iterations of her diary, but the actual diary, her own actual prose, if somebody were to read an excerpt from that diary and you just closed your eyes, you would think it might be somebody from today. Very contemporary observer, no filter, I guess, is the best way to put it.

Anybody who refers to a fellow Confederate matron or socialite as a miscreant is also going in the book, as is the fact that she said this person was a miscreant. I liked her observations about things, and also the fact that Mary Chesnut, despite growing up among slaves, despite owning slaves, Mary Chesnut was very conflicted about slavery. I found that fascinating.

Alison Stewart: Why was South Carolina such a hotbed?

Erik Larson: South Carolina, this is one of the enduring. It's not really a mystery, but South Carolina had always been a persnickety state dating back to the early 19th century. Even before, throughout its history, honestly, since the crafting of the constitution, South Carolina was always a thorn in everybody's side. In fact, so much so that other states, as South Carolina barreled towards secession, other states actually were concerned that South Carolina would lead the way because they would have no credibility because South Carolina was always doing this crazy stuff. It was an amplification of what South Carolina had always been.

Alison Stewart: I want to talk about James Buchanan. This is my favorite part.

Erik Larson: Okay.

Alison Stewart: First of all, what do you see as Buchanan's role in ushering in the war?

Erik Larson: James Buchanan was a bachelor. This was a shocking thing to those who followed the electorate back in that era, and people on his side of the fence went to great lengths to make sure that was okay with people. In fact, one guy came up with the solution for how to resolve the mystery of this bachelor in the White House, and he said, James Buchanan is married to the Constitution. That's how he will do this. The problem was that James Buchanan, James Buchanan until he became president, showed every sign of being likely to be a fantastic president because he had excelled in every political job he had had before until the presidency.

He becomes president. The nation is starting to fall apart late in his term, but starting to fall apart. He does not want a war on his time. He wants anything, but he will go to huge lengths to keep that from happening. You have James Buchanan in the White House basically doing nothing to stop this national crisis. At the same time, you have Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, who has vowed to himself that he would not speak out on the national crisis until he was officially president after the inauguration on March 4th of 1861.

Now, he made his views known through friendly newspaper editors, through politicians, and we know, of course, how he spoke about his attitudes about slavery, but he, too, was trying to stay out of the fray. Basically, you had this vacuum, and Major Anderson, who's out there at this fort in Charleston Harbor, this 50-foot-tall sea fortress, is getting no direction from anybody, no direction as to how he should behave, what he should do, whether he should surrender, whether he shouldn't.

The entire fate of America was in the hands of this poor guy, Major Robert Anderson, who, by the way, was southern born, a former slave owner, but was himself deeply loyal not to the United States, but to the United States army. That was the setup before the bombardment.

Alison Stewart: You're listening to my conversation with Erik Larson, author of the book The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War. It was our Get Lit with All Of It September Book Club selection. We'll have more with Eric along with questions from our sold-out audience after a quick break. This is All Of It.

[theme music]

Alison Stewart: You are listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Let's continue the conversation with our Get Lit with All Of It Book club author for September, Erik Larson. We spent the month reading his new book, The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War. Thanks to our partners at the New York Public Library, 6363 of you were able to check out a copy and read along with us. We had a sold-out crowd at our event, and as always, our audience had some really great questions. We'll get to some of those in just a minute, but first, let's dive back into my interview with Erik Larson.

[theme music]

Alison Stewart: What was the decision that Anderson made during the course of the escalating situation that proved very consequential?

Erik Larson: Well, he made many, but one was probably, I think what you're thinking of is when Major Anderson was put in charge of federal forces in Charleston Harbor, he was put in charge of a number of fortifications, one of which was Sumter. One was Fort Moultrie, also a sea fortress, but on a land-based sea fortress. It was still very much a full-service, fully functioning fortress where Sumter actually was not yet there. Major Anderson comes, and he's put in charge of this operation, hated by every Charlestonian, every South Carolinian.

South Carolina, December 20, 1860, decides that it's going to secede. Things get very dicey in Charleston Harbor, and Major Anderson decides on his own. He cooks up a plan to move his 75 men, who at this point are stationed at Fort Moultrie on land around Charleston Harbor. He cooks up a plan, a secret plan, to move these men and their families to Fort Sumter, which was more or less believed to be impregnable at that point. He cooks up this plan. He's going to do it on the evening of Christmas day. He can't.

The weather is too bad. He does it the evening of the next day, still counting on people to be distracted by the holiday, which is a huge holiday in the south. By God, he pulls it off, and he occupies Fort Sumter. The next morning, the first indication to Charlestonians that something really bad has happened overnight is that Fort Moultrie, this land-based fortress, a smoke, and fire are coming out of Fort Moultrie because Anderson has left behind a couple of officers and men to burn the gun carriages and spike the cannon. Charlestonians awake to see this fort on fire and to see this flag flying from Fort Sumter and they were just like, sticking a stick in a beehive.

Alison Stewart: Before we leave, people, I want to talk about Edmund Ruffin. He's one of the successionists you spend time with. What were his arguments for why the southern state should leave the Union?

Erik Larson: Edmund Ruffin is my second villain, and Edmund Ruffin simply believed that the North was a tyrannical force out to subdue and crush Southern aspirations and there was nothing that anybody could do to convince him otherwise. He hated the North. He hated Yankees. He was a Virginian, and he hated being a Virginian because Virginia was not doing anything about secession.

Then he made it his mission to go around to other southern states, to South Carolina in particular, and stump for secession in all these places. Eventually, he made himself an unofficial South Carolinian. I love a good villain, but I loved him as a character because he was so rotten. He was just--

Alison Stewart: He's so rotten?

Erik Larson: He was just so rotten. He just hated the Yankees so much. Then, I don't want to reveal certain details because there are. Yes, we know what happened, but there are spoiler alerts about things that Ruffin does. Well, I definitely don't want to give away the ending, but he was a horrible guy.

Alison Stewart: Yes.

Erik Larson: So yes.

Alison Stewart: One thing that was so clear is there was so much miscommunication.

Erik Larson: Yes.

Alison Stewart: So much miscommunication. How did the invention of the telegram change the way that business and politics were conducted?

Erik Larson: One of the sub-themes of the whole story really, was miscommunication and it's interesting. Mail was the primary means of communication, and when things were up and operating, mail was actually surprisingly good, surprisingly efficient means of communicating, but it was not immediate. The telegraph had come along, and this was a magical thing. Almost instantaneous transference of messages over great distances.

One fatal flaw of the telegraph was that it was a leaky system at different nodes along the way, information could be passed on to somebody who wasn't supposed to have it. The telegraph for really hypersensitive was not always used. You relied on the mail, and then the mail would cross, you'd have one person saying one thing in the mail and something else coming back in the mail, and it was just really, really a mess.

Alison Stewart: Do you think there's any scenario that would have avoided the Civil War?

Erik Larson: You're asking me to engage in speculative history, and something I really have said I would never engage in.

Alison Stewart: You have written about Civil War either.

Erik Larson: I'm going to stick with this one. The thing is that Civil War scholars who have greater depth and grasp of this than I have tackled this same question, have not been able to come up with any persuasive scenario that would have avoided the Civil War. One always has to ask, had there been a stronger president than Buchanan in office, what might the consequences have been? Had they been a stronger, more loyal president than Buchanan? Beyond that, I just can't. I can't say.

Alison Stewart: Let's get to questions from the audience.

Speaker 1: Thank you very much. I love the book.

Erik Larson: Thank you.

Speaker 1: Question. You can't put everything in the book, so what are one or two really good things that you had to leave out?

Alison Stewart: That's a good question.

Erik Larson: How do you know that you can't put everything in a book? That's a great question. Before we're done here, I may think of something, but believe me, I think all my favorite things are in this. All my favorite things are in this book, and if they're not in the book, they are in the footnotes. However, I have to address that also. When I gave this book to my editor starting out, I thought, "Okay, this is going to be a historical suspense thriller. It's going to 250 pages max. By the time I turned it in to my editor, it was 800 pages, and she got it down to 500. There must be something on the [unintelligible 00:29:20]

Speaker 2: If Lincoln hadn't mistakenly assigned the ship Powhatan to go to two separate locations at the same time, what do you think the impact of that would have been, considering that Seward spent a lot of time undermining, fixing it?

Erik Larson: That was an interesting part of the story also. If he had not made that error, if this particular warship had gone on the Sumter mission, would anything have changed? My attitude there is I've thought about that quite a bit also. My attitude is if that warship had gone with this relief expedition when it did, the war simply would have broken out a lot sooner with a lot more casualties.

Speaker 3: Hi, I'd like to ask you a question about how we have taught the causes of the Civil War in the United States and I wonder if in your research-- I'm understanding that may have changed over time a bit, and I wonder if you came across that in your research at all.

Erik Larson: What I found fascinating and hit me very, very early on, at the start of the 20th-century historiography about the Civil War bent toward this concept of state's rights and that persisted for a lot longer than it actually should have. One of the things that became very clear to me very early on. What I always try to do is I try to clear my head of whatever the presumed history, the presumed themes, and so forth, what the presumptions are that have gathered more cement if you will than they should have, and just see for myself what's going on.

When you read into the actual documents of the secession conventions and you read Mississippi's secession ordinance, and other documents from this period, it's all about slavery. It is all about slavery. It is explicitly about slavery. How scholars let themselves get sidetracked into this whole state right back at the start of the 20th century, I have no idea, but it just leapt out at me.

Alison Stewart: My final question for you. There seems to be a renewed interest in the Civil War. There was Manhunt on Apple TV plus there's Oh, Mary! on Broadway. Why do you think there's this renewed interest in the Civil War?

Erik Larson: Maybe it's because of our contemporary political situation, but also, I don't know that the interest has ever waned for a substantial period of time. It just always waxes and wanes and never goes away. Before I embarked on this book, when I was still wavering before January, 6 convinced me that it was a very contemporary story. I asked my good friend Siri how many books had been written on the Civil War, and she said, 60,000.

Alison Stewart: Wow.

Erik Larson: I wrote the book anyway.

Alison Stewart: It was great. Erik Larson, everybody. Thank you so much-

Erik Larson: Thank you.

Alison Stewart: -for your time today.

[applause]

Alison Stewart: That was my conversation with Erik Larson, author of the new book The Demon of Unrest: A Saga of Hubris, Heartbreak, and Heroism at the Dawn of the Civil War. It was our September selection for our Get Lit with All Of It book club. Up next, we'll speak with a folk duo who draw inspiration from this 19th-century history in their songwriting and in their costumes. A special performance from Sons of Town Hall is up next. Stay with us.

[theme music]

[00:33:25] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.