Glenway Wescott's Images of Truth

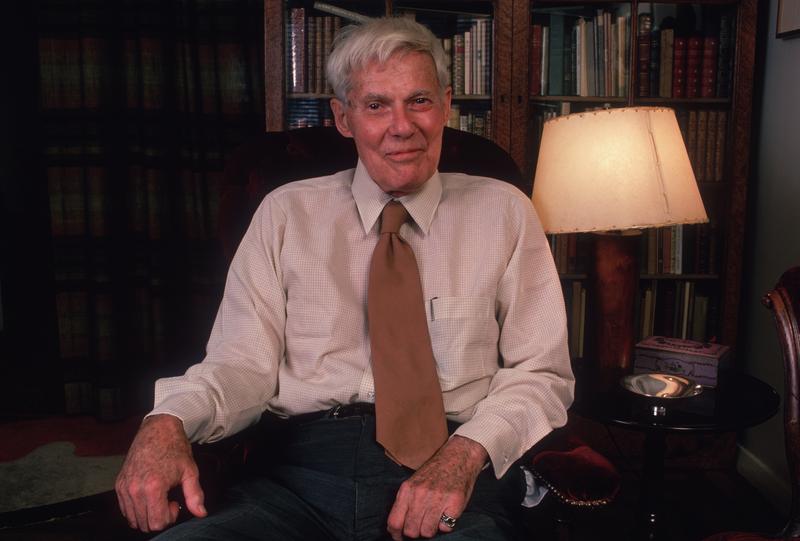

Breaking a seventeen year silence, Glenway Wescott talks about his new book, Images of Truth, at this 1962 Books and Authors Luncheon. The gap seems almost as much a topic of conversation as what he chose to end it with. Referring to "my odd, sporadic, but persistent career of literature," Wescott reminisces about last appearing at one of these promotional events in 1945. His book consists of essays and remembrances of six authors: Somerset Maugham, Colette, Isak Dinesen, Thornton Wilder, Thomas Mann, and Katherine Anne Porter. How did he settle on these six? "Time and chance."

Maugham, he disarmingly reports, has never much liked Wescott's fiction, telling the then young writer he had a better chance of becoming a good essayist, if he worked at it. He goes on to sketch in rather vague terms the nature of their relationship. Katherine Anne Porter, on the other hand, seems to be more of a friend. He describes what a hard time she had making a living while working away on her novel Ship of Fools. Now, with its success, she is "like an old oil prospector who finally strikes a gusher." But she is having tax problems, he confides, having spent a large share of the book's profits on an emerald. It would have been a small emerald if she had made money earlier, but as she told Wescott, "with every year I had to wait for it, it got bigger and bigger."

Glenway Wescott (1901-1987) is one of the enigmas of mid-century American literature. A promising novelist and short story writer, he went silent after the publication of Apartment in Athens in 1945. The book he is introducing at this luncheon was a collection of older pieces, some written many years before. It led to no more works of fiction or non-fiction, although Wescott's journals were published after his death. The silence is puzzling as it was hardly due to lack of recognition or literary connections, both of which he had in abundance. As the New York Times noted in its obituary:

Mr. Wescott, who was a former president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, achieved literary acclaim when he was 26, with the publication of his second book, ''The Grandmothers.'' The novel, the saga of a pioneer family transplanted from New York State to Wisconsin in 1846, was the Harper Prize Novel for 1927 and became a best-seller. Constantly in print, the book was re-issued last year by Arbor House. ''He was a very important writer, very much in this country like E. M. Forster in England,'' said a professor of English at Trenton State College, Hugh Ford, who is writing a biography of Mr. Wescott. ''He wrote only a few novels, some short stories, essays and reviews, but everything he wrote was done in high style - almost Flaubert-like in certain ways, and one of the finest stylists in recent years.''

One possible explanation for Wescott's reticence could be an unwillingness to depict the unconventional personal life he led. With Monroe Wheeler, Director of Exhibitions and Publications at the Museum of Modern Art and the photographer George Platt Lynes, he maintained an open three-way homosexual relationship which would have scandalized the literary establishment, not to mention the reading public, of the day. But many other writers of the time found ways around such restrictions. The novelist Michael Cunningham, quoted on the website Open Letter Monthly, gives perhaps the most sensible answer.

“There is, to my knowledge,” Cunningham writes, “little information about why he stopped writing fiction, though I tend to believe that writers who stop writing do so for reasons ultimately as mysterious as those that drove them to attempt writing in the first place.”

As for the journals, they consist largely of narrating an active, if not hyperactive, social life featuring such a star-studded cast that the charge of name-dropping becomes a danger. Howard G. Williams, reviewing one of these volumes in Lamda Literary, suggests:

…ultimately, perhaps Wescott felt that he might enjoy indulging in an active intellectual and sex life…more than in creating a fictional world, in the journals, he states, “I live novels instead of writing them.”

It is difficult to say if this reasoning is the creative artist's ultimate hubris or the result of a triumphant untangling of whatever initial neuroses moved a person to try making art in the first place.

Audio courtesy of the NYC Municipal Archives WNYC Collection.

WNYC archives id: 150273

Municipal archives id: LT9470