Elizabeth Kim, politics reporter for WNYC and Gothamist, Jessica Gould, WNYC/Gothamist reporter, and Stephen Nessen, transportation reporter for the WNYC Newsroom, review the accomplishments of and challenges faced by Mayor de Blasio and ask listeners to weigh in with their "grades."

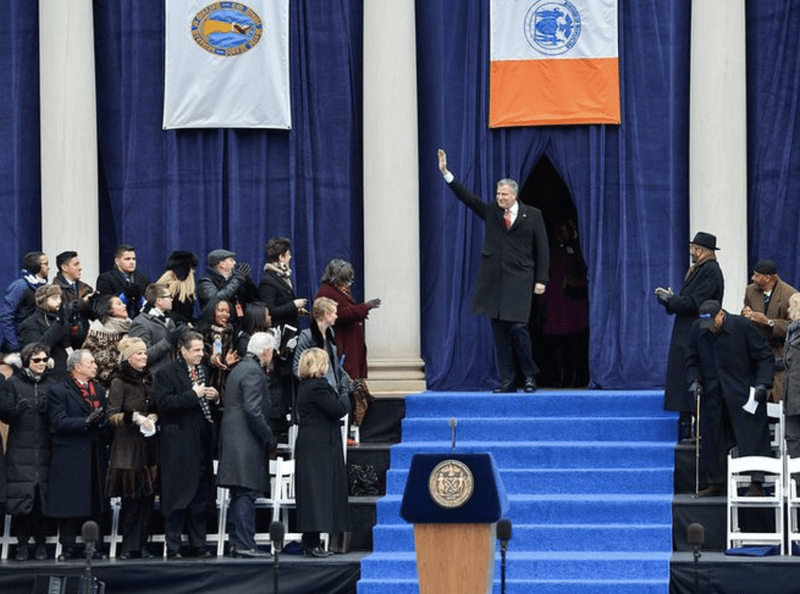

Brian Lehrer: It's Brian Lehrer show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We begin today by grading Bill de Blasio, as he nears the end of his eight years as mayor of New York. "Grading Bill de Blasio" is a project led by three WNYC and Gothamist reporters who will join us in a minute. Stephen Nessen, our transportation reporter, Jessica Gould, our education reporter, and Elizabeth Kim, who covers mayoral power. First, those three, plus some colleagues doing photography, have been hitting different parts of the city and asking New Yorkers what they think the mayor's biggest accomplishments and failures have been. Here's a one-minute montage from recent interviews done in Harlem, the Upper West Side, and the Bronx.

Interviewee 1: He left the city in a worse position, so he's accomplished nothing. I'm very disappointed in what's happened under his leadership.

Interviewee 2: His biggest accomplishment was trying to bring the city back together after the coronavirus, getting the vaccination on roll as far as getting the city vaccinated, trying to open up the city again, you know what I mean? He got Broadway back open.

Interviewee 3: I wish it was less crime. I wish the city was cleaner the way it was prior to the pandemic. I wish more services were provided for the homeless people. I'm noticing more and more homeless people on the subways.

Interviewee 4: I think that his administration did a lot of great things pre-K for all of us, I think. Life-changing for a lot of people, and the administration hasn't gotten, I think, the kind of credit that they deserve for that.

Interviewee 5: The best thing he did, he kept us informed about the Corona. He always kept on top. Every morning he was on that camera on TV and he let us know the answer to what was going on, and that was the most important thing that we needed to know.

Interviewee 6: The first responders, I don't believe in him forcing them to go get vaccinated or lose their job. No, you supposed to take care of the first responders first before anybody.

Brian Lehrer: New Yorkers from Harlem, the Bronx, Upper West Side, with some thoughts on Mayor de Blasio, part of the reporting for WNYC and Gothamist "Grading Bill de Blasio" series. Listeners, we'll invite your grades, not yet, in just a minute, don't call yet, we'll tell you how. Let's welcome our guests first, WNYC and Gothamist reporter, Stephen Nessen, our transportation reporter, Jessica Gould, our education reporter, and Elizabeth Kim, who covers mayoral power. Hi, Jessica, hi, Stephen, hi, Liz.

Jessica Gould: Hey, Brian.

Stephen Nessen: Hey, Brian.

Elizabeth Kim: Good morning.

Brian Lehrer: To set this up for our listeners and get calls coming in on the right track, how did you do this? Did you actually give him letter grades? Jessica, since you are the education reporter, maybe you could explain the grading system.

Jessica Gould: I was actually not in charge of the grading system though I am the education reporter, so I'm going to pass that on to someone else, but I think that this would be a very mixed report card.

Brian Lehrer: Liz, are you on the formation of the assessment?

Elizabeth Kim: For this story, we ourselves did not give the mayor a grade, but like Jessica said, it's a very mixed kind of record, and I think we laid out both the achievements and also the areas in which the mayor fell short. What we mean by grading Bill de Blasio is when we did go out and interview New Yorkers on the street, we did ask them to submit their grades and we gave them, they could go from A to F. I will say that for the first round of interviews that we did that you played some of the clips there, it was a range. He did get an A, he also got an F, but there were also a lot of Bs.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, here we go, grading Bill de Blasio. Like your best elementary school teacher, we want you to be firm, but fair, and you can grade the mayor overall or grade him on a specific area of interest to you. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. After we're done with the conversation, if you haven't seen it yet, I recommend you to the really great package and there's more to come that you can read on Gothamist with Stephen and Jessica and Liz doing and there aren't letter grades.

It is a narrative on some of the big topics that were covered that I mentioned before. Our reporters did mostly, and I'll mention them again, education, transportation, and income inequality, housing is part of that, they're doing them. You do you, you can grade the mayor overall or grade him on a specific area of interest to you, especially if any of his policies affected your life directly. 212-433-WNYC 433-9692 or grade Bill de Blasio on Twitter, because that's what people do on Twitter @BrianLehrer, just tweet @BrianLehrer.

As calls are coming in, Liz, I'm going to start on content with you because your recent article was the preamble to the set and maybe asks the most important question, at least to my mind, which is, did Blasio make a dent in the tale of two cities, New York's income inequality. You cite independent figures from just before the pandemic that seemed to say, yes, he did dent income inequality. In fact, he bucked a national trend on that taboo. Can you describe some of who found what?

Elizabeth Kim: Sure. Bill de Blasio basically premised his mayoralty on this idea of income inequality with the tale of two cities slogan. In recent weeks, he's been saying that when he's asked by reporters, "Did you think you made a dent [inaudible 00:06:10] income inequality gap in New York City?" and he has consistently said yes. He cites policies like universal pre-K, his affordable housing plan, but he hasn't been able to really show us any data or evidence.

He often likes to point to poverty, poverty statistics, which are good statistics to look at, but that's not really speaking about income inequality. I decided that I would ask a group of economists to look into this and what they told me is there's actually very good data on this and it's kept and housed and organized by the independent budget office. They have tax filing data for all New York City residents who file taxes. This represents about 7 million people, so it's a very, very large sample and it's considered extremely reliable when you want to study things like income inequality.

I basically reached out to both the IBO and then James Parrott, he's an economist at The New School, and some people might remember he was also part of the Dinkins administration as their chief economist. They basically looked at this dataset from 2010 to 2019. They crunched the numbers, they did their own separate analyses, and what they found was there's something that happens in 2014. Now, if you know anything about income inequality, it's extremely difficult to reverse.

Basically, you look at the pattern in a city like New York, which has very huge income inequality, and what you'll see if you look at a graph is you'll see it's either steadily creeping up increasing, or it will stay flat, but around 2014, there's a kink in the curve and it starts to go down. It's not a huge swing by any imagination, but if you look at the data, it definitely begins to turn downwards. This was actually, I think, to the IBO, it was quite surprising.

It wasn't surprising to James Parrott because he's basically spent his career looking at income inequality in New York City and what he told me is that this is historically significant. He says that "this is a change from four decades of increasing or flat income inequality." I think the question that policy experts and economists will go on to debate is how much credit do we give the mayor for this?

Brian Lehrer: Well, that's the question. Stephen Nessen, be patient, we'll get to you on transportation. Jessica Gould, be patient, we'll get to you on education. Elizabeth Kim, to stay on this, how much can your sources who've actually got data showing a decline in income inequality credit specific de Blasio policies? I think for one thing, back to the 1990s when we had a Conservative Republican mayor, Rudy Giuliani, and we had a Democratic president, Bill Clinton, and the economy was booming and it helped New York, like it helped the rest of the country, and Rudy Giuliani said, "Oh, it was my policies, my conservative policies," and Bill Clinton said, "Hey, it was my liberal democratic policies," but the economy was going up at the same time.

I think before the pandemic, Donald Trump, when he was president, the same years as de Blasio was mayor, was also boasting of record-low unemployment among Black and Latino Americans, and a bit of a closing of the wage gap nationally with general economic growth. In that context, how much do your expert sources credit specific de Blasio policies?

Elizabeth Kim: If you ask someone like James Parrott, he does give de Blasio a lot of credit, because he looks at a lot of pro-labor policies that the mayor either implemented himself or campaigned and pushed for. Let's start with the minimum wage, for example. Now, the fight for what's called the Fight for $15 an hour, that was not something that the mayor waged by himself, of course, but he did lobby for it. He didn't have the power to raise the minimum wage, but he did put pressure on the governor to do so. In that respect, policy experts, you can give de Blasio credit for something like that and that did raise the income levels of a lot of low-income, New York City residents.

Another example or policy that Parrott points to is coming in and settling contracts with municipal workers. Now, his predecessor mayor, Michael Bloomberg, had basically stalled on those negotiations, and he did not settle those contracts. Mayor de Blasio by coming in, settling those contracts, again, that's an example where he lifts the wages of working-class New Yorkers.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead.

Elizabeth Kim: There are other examples that you can point to too. The mayor himself, he likes to point to universal pre-K. There's a case for that, because if you think about what universal pre-K is, and the mayor himself has described it as basically what people like to say, a wealth transfer. These are families that would normally have to either pay for that, whether you call it childcare or preschool, they no longer have to pay for that. That becomes money in their pocket. I think though, what Parrott says is there's not clear data on that specifically yet, but the reasoning holds, he says.

The same goes for affordable housing. What Parrott likes to point to is rent freezes, for example, the rent freezes that affected two million New Yorkers. That again is a way of giving a wealth transfer. Basically, those people did not have to pay higher rents in those years that there was a rent freeze.

Brian Lehrer: If they lived in rent-stabilized apartments. That's all very interesting. I think people forget the $15 minimum wage and de Blasio's role in that. He was really pushing it, as I recall, at the beginning of his mayoralty, and then Cuomo adopted it statewide, and then it wound up being a state thing and people talked about New York State's $15 minimum wage or glide to $15. I think this is one of those cases where de Blasio got Cuomo into a bidding war on who could be the more progressive. Also, the other private sector policies that de Blasio came in with that you mentioned, the paid sick leave, family leave, things that were not citywide policies before he came in.

Let's take our first set of callers on "Grading Bill de Blasio." Here's what we're going to do. We're going to start with somebody that gives him an A, and then we're going to go down because we have an array of callers, go down the grading ladder here with a few. Then we'll get into the other issues or grading areas as reported by our education reporter, Jessica Gould, our transportation reporter, Stephen Nessen. Sandra in Harlem, you're on WNYC. Hi, Sandra.

Sandra: Good morning.

Brian Lehrer: Spoiler alert, you gave the mayor an A. Tell us why.

Sandra: I gave him an A because-- education. His most important achievement is definitely the pre-K and pre-K programs. New Yorkers are seeing the effects right now. These programs are going to have positive consequences in the long run as well. I don't have children, but many, many of my co-workers are benefiting from the pre-K and pre-K program.

Brian Lehrer: Sandra, thank you. Oh, you want to do another one. Go ahead. Another reason.

Sandra: No. My only criticism is all the time that he lost in getting rid of the horses in Central Park. Waste of time. Those horses live much better than many of New Yorkers. Thank you so much.

Brian Lehrer: A, with an asterisk. Sandra, thank you very much. Call us again. Gabriel on the Upper West Side, you're on WNYC. Hi, Gabriel.

Gabriel: Hey, Brian, how are you?

Brian Lehrer: I'm okay. Oh, wait a minute, Gabriel. Hang on, because I was going to go to you next because you're giving him a B. I see that Anthony in the Bronx is calling with a B plus, so if we're going down the ladder, B plus is higher than B. Anthony, you're on WNYC. Gabriel, hang in there, you're next. Hi, Anthony.

Anthony: Hi, Brian. Good morning.

Brian Lehrer: Tell us why a B plus, back it up.

Anthony: Well, for one thing, we first got to take in consideration with his predecessor, Bloomberg put in office, actually staying in office the extra 12 years to see his plan come into fruition, which didn't benefit the average New Yorker. It only benefited the wealthy and the rich. What I mean by that, it wasn't so much about what Bloomberg did. It was about what Bloomberg didn't do in terms of education, fair wages, and things of that nature and putting into charter school systems and taking away money from the public school system. Commercializing the poor neighborhood education, because in most cases, you don't see charter schools in white neighborhoods.

Brian Lehrer: Anthony, let me jump in. I want to move you ahead from grading Michael Bloomberg's 12 years to grading Bill de Blasio's. Why a B plus for de Blasio, except that he's not Michael Bloomberg?

Anthony: Well, for the simple fact that he was in opposition to the charter school system. He was also concerned about the well-being of all of New Yorkers, not just one particular set of New Yorkers.

Brian Lehrer: Why not an A, any particular reason?

Anthony: Well, because actually, the reason why I didn't give him an A is because he and the former governor, they couldn't get on the same page. Neither one of them wanted the best, and for that, I give them both for B plus.

Brian Lehrer: Anthony, I appreciate it. Thank you call us again. Now to Gabriel on the Upper West Side, who's going to grade de Blasio a B. Gabriel, hi, tell us why a B.

Gabriel: Hey, Brian. I did a B because well, I think he did his best in terms of trying to be a just mayor and like our previous caller said, he was working against a lot taken on the mantle from the mayor before him who really set us back in many ways, even though on the surface, it seemed like it's set New York forward. De Blasio, this man is a Sandinista Democrat who's coming against, not just the regular democratic status quo, but also probably a lot of Mafia in New York, I would imagine. He really tried his hardest. He ate his pizza with a fork and knife. It's like, what are you going to do? I once met him on a street corner clandestinely. He was standing outside of a jazz club.

Brian Lehrer: Clandestinely? Was he selling something?

Gabriel: No, it wasn't that clandestinely.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead. You've got Sandinista. You've got mafia. You've got clandestine on the street corner. Oh, going here. This is a good call. Go ahead, Gabriel. What happened?

Gabriel: [inaudible 00:18:42], Brian. He was standing outside of a jazz club on MacDougal Street. I was on my smoke break and he's dressing a three-piece plaid custom suit. I didn't even know how tall he was. I was like, "Hey, Mr. Mayor, what's up?" This man daps me up like a bouncer for one, which I don't think Bloomberg or Joseph Lhota would ever have done. I'm like, "Hey, you like jazz?" He's like, "Yes." Then as he's getting into his car, he's with this young woman of color and I was like, "Hey, are you hiring, like Black people with nose rings these days?" He goes, "That's my daughter." She turns and she goes, "You know what, yes. In fact, he is," and they close the door.

I was like, "That is a cool mayor. He's probably coming up against a lot." I've never seen him in a three-piece suit in a press conference. He tried to do his thing, but I don't think he really could express himself in a way that resonated with New York, and it's because he's from Massachusetts.

Brian Lehrer: Is that why the B that he didn't connect?

Gabriel: That's the B. He really did his best. He didn't connect in a way that I think he has the capacity to.

Brian Lehrer: By the way, de Blasio is not known for going out and partaking of the Arts in New York. Who was the band in that jazz club if you happen to know?

Gabriel: I'm not sure, it's a small jazz club on MacDougal Street and it's really good. I don't know who was playing, it wasn't a big--

Brian Lehrer: Big name

Gabriel: It wasn't a blue note.

Brian Lehrer: I got you. Thank you very much.

Gabriel: Let me plug it.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead.

Gabriel: It's called La Lanterna, I'm going to plug that place, La Lanterna on MacDougal, right next to Tokyo Record Bar.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much, Gabriel. Call us again. He's got a D, nobody's calling with a gentleman C that I see, but Manny on the Lower East Side is calling with a D. Hi, Manny, you're on WNYC on "Grading Bill de Blasio." What you got? Why a D? That's bad.

Manny: I'm giving a D and I'm giving an F for education. In terms of income disparity, I just want to remind people that he was paying poor people to move out of the city. The amount of gentrification that has happened in poor communities under his leadership is part of the reason that there's been lower disparity in income because he just made poor people leave one way than the other.

Brian Lehrer: What do you mean he was paying poor people to leave? That was initiative during Giuliani, I recall, but what did de Blasio--

Manny: There was also something, he was paying for people's rent in Newark, New Jersey.

Brian Lehrer: Oh, right. When there was an affordable housing shortage in New York.

Manny: Correct. Those people leaving, and low income was going and people with better incomes on the [unintelligible 00:21:28].

Brian Lehrer: That's right, and Newark was talking about whether it was like a form of "poor people dumping."

Manny: Right. Exactly. Then in terms of education, three things, one is he's exploded the central department of education. I was an educator for 30 years, he exploded money out of schools into bureaucrat or educrat situations. In terms of pre-K and 3-K, people forget for poor people and low-income individuals, there was Head Start already, who has now been able to take advantage of free pre-K and 3-K on wealthier people. That's who it's actually helped more than actually poor people. Number three in education, he's done nothing, nothing, and he never did even when he was on the school board anything about desegregating the school system. He's done nothing about it. Now walking out the door, he's passed some legislation so he can say he did something. For seven and a half years, he did nothing [unintelligible 00:22:33].

Brian Lehrer: He didn't like to say the word segregation, I know, he finally got pushed into that corner, that's fair. Manny, thank you very much. Jessica Gould, we're going to get to you in a minute, as our education reporter on that. Manny's particular education critiques, but one more as we get to the bottom of the ladder. Eric in Forest Hills is grading the mayor an F. Now, Eric, you know an F means he gets left back, I guess that would mean he would have to remain as mayor and you probably don't want that, but why an F?

Eric: Where do I start? Let's take the subway, for example. I rode the subway. I had a homeless guy follow me out of the subway, relieve himself on the street corner, and then on my way home from work on the subway, there was a homeless man who pleasured himself in front of everyone. I've been living in New York City for 22 years, the quality of life in this city has taken a serious nosedive in the last 8 years. I do not feel comfortable in letting my family ride on the subway by themselves without me.

Brian Lehrer: How much do you blame de Blasio's policies?

Eric: I know in my experience, my day-to-day living before his administration, those problems seemed to be much more under control. Now, I don't know the granular details of his policies, but I can see the difference in just my everyday experience. I'll give you another example, 311, which revolutionizes access to city services to common New Yorkers. When Bloomberg was in office, there was a car horn beeping constantly outside my window, I called 311, it was taken care of in 25 minutes. In my neighborhood, and just a year ago or two, the same thing happened, no one ever showed up. That horn beeped the entire weekend and the horn, it died out on its own.

Brian Lehrer: The battery ran out. Eric, I'm going to leave it there. Thank you very much. Please call us again. Jessica, that was some set of calls, that was talk radio in all its glory right there. People grading de Blasio from A down to F. What were you thinking as you heard the whole thing? What about the particular education critiques that that one caller who graded him a D was focusing on?

Jessica Gould: I think that in many ways, de Blasio has wanted to be an education mayor and as he moves forward, he's obviously making education a big part of his pitch for what we all assume will be a run for governor. He's trying to emphasize what he considers and what many consider to be his greatest success with pre-K. Within two years of taking office, they had dramatically increased the seats for 4-year-olds at the public schools to now it's 70,000 seats, I think it was 68,000, within 2years, so that now everybody who wants to seat in pre-K, theoretically should have one.

There have been some flaws. There haven't been enough seats for kids in pre-K with special needs, special education seats and there's been issues with bringing in nonprofits, the caller mentioned Head Start, bringing in nonprofit operators into this sort of mixed system of traditional public schools and nonprofits so that there's been pay disparities between the teachers, which have been somewhat resolved, and then also between the operators of these programs. It hasn't been seamless or perfect, but for many parents, it's been a huge boost. It happened pretty easily and quickly.

The research continues to show positive outcomes from going to pre-K and it's a big financial savings. Just a couple of weeks ago, I was listening to your show and a mom called in to thank the mayor for doing pre-K. I think it's largely considered his greatest success, it was also what he spoke about the most when he was campaigning back when I covered him in 2012, I guess that was. There's that, and then if that's his greatest achievement, I would say on the flip side, for many, his greatest disappointment has been on integration and segregation. You mentioned that he was reluctant for years to even say the word segregation.

This happened at a time when New York City's public schools were grabbing headlines for being among the most, if not the most segregated schools and the most segregated system in the country. He never took the bold action that so many people who were advocating for integrating the schools wanted. He swung and he missed as it related to the SHSAT eliminating the test for the specialized high schools. He rolled it out in a way that was very top-down, that didn't engage members of the community, including members of the Asian community, who disproportionately send their kids to those schools and who rely on those schools for uplift of immigrants.

Brian Lehrer: Who, by the way, disproportionately voted for Curtis Sliwa for mayor last month, so something to do with that maybe.

Jessica Gould: There were tons of protests of the mayor and particularly Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza, during that period. There was just a troop of protesters, many of them from the Asian community who would follow them around, protesting both their rhetoric and this effort with the SHSAT and then eventually gifted and talented, but that effort failed, he backed away saying he hadn't gotten the buy-in he needed to eliminate the test, which could have integrated the specialized schools more and the specialized schools are only a small proportion of the schools in the system.

Brian Lehrer: Let me follow up on the segregation question this way, Jessica. De Blasio has tended to hang school segregation on housing segregation, which gets back to the income gap and which neighborhoods people can afford, so he prefers to focus on mixed-income housing, rezoning for mixed incomes in the same neighborhoods and that school integration will flow from that, but he finally, as you say, in the last couple of years did start talking about school desegregation per se. What changed? Did the housing integration efforts bear any fruit in terms of school desegregation?

Jessica Gould: UCLA Civil Rights Project, which identified New York City as the most segregated school system, New York State really, but New York City specifically as most segregated a few years ago, came out with an update and said that the school system is still extremely segregated, and it became even more segregated for Black students. Black students were more likely to go to schools with other Black students and less likely to have white students at their schools. I know Liz is going to talk about the successes and shortfalls of his housing policy, but in terms of desegregation, that effort didn't really work.

It came at a time when gentrification was already poised to potentially integrate some schools. There were policies in place. Some leftover from the Bloomberg Administration as it related to selective admissions at middle schools and high schools that tend to contribute to segregation of schools. Using tests and grades, and attendance to decide who gets in. That can allow segregation to continue even in neighborhoods that are becoming more diverse through gentrification.

Brian Lehrer: One thing before we go to Stephen and transportation, on universal pre-K. Popular, obviously, unambiguously in the W column, at least in terms of public opinion, but are there metrics to say, if it's really closing the educational outcomes gap? I think it was sold to us as if you're going to see it, by the time they get to third grade, there are going to be more kids reading on grade level, doing math at grade level than before there was universal pre-K. There'll be less inequality on that. Can we measure that yet?

Jessica Gould: I believe that the third-grade scores did show some improvement. I think this question about how beneficial pre-K is has been litigated in the research over the years. Largely, it's linked to better educational outcomes, particularly as it relates to behavior and going on to college, less so and standardized tests, actually, according to the most recent research I've read. I think there needs to be more done to look at New York City specifically. It's going to be really hard because this cohort of students who benefited from pre-K are also the cohort of students who were affected by the pandemic. It's going to be very hard to measure that.

Brian Lehrer: Now to Stephen Nessen, our transportation reporter who wins the Congressional Medal of Patience for being the third reporter up on a three reporter segment with a lot of calls to boot. First word at the 35-minute mark, the Congressional Medal of Patience. Stephen, one thing we can say, is the bicycles hate the drivers, the pedestrians hate the bicyclists, and everyone hates the E-bikes. Besides this ongoing war of all against all on the city streets, how do you start to assess the mayor on transportation?

Stephen Nessen: Yes. Hello, Brian. It is tricky. Something that I tried to keep in mind is what can the mayor control? I think as a transportation reporter, I cover all the different ways that people get around. All the ways you just mentioned, all the issues that stem from that. You'll find a lot of the time there's sort of overlapping jurisdiction. The state controls certain bridges, certain roads, the mayor can only do so many things. I tried to look at what can the mayor control? We're talking about looking at everything through an equity lens, so that helps narrow things down as well.

Just to mention what I didn't write about, because I'm going to write about it next week, heads up, is about the sort of key signature issue of Mayor de Blasio's terms, has been the Vision Zero campaign, the Vision Zero project, which didn't exist before him. It's somewhat hard to measure how was it before because there wasn't a Vision Zero before the mayor. We can look at the stats like fatalities and just to mention very briefly, when the mayor took office, there were 299 people killed on the road, that's pedestrians and cyclists, by vehicles. That was before the mayor took office. This year, it's 227 deaths. A slight change.

Brian Lehrer: Before the pandemic, which of course, changed so much about so much, it was down from that, right? Can we say unambiguous success pre-pandemic or no?

Stephen Nessen: I wouldn't use the term success. There were 205 people that died in 2018. I think that was the lowest year for traffic fatalities. There were also 60,000 people injured that year, which is higher than this year. Which is to say, let's not get into all the nitty-gritty [unintelligible 00:34:56] of it.

Brian Lehrer: I learned in third grade that 220 not zero.

Stephen Nessen: Yes, exactly. A couple of things that the mayor did have control of that I wanted to focus on is the Fair Fares program, which we don't talk about too too much. It's an incredible program, that the mayor had to be dragged into kicking and screaming by the city council, specifically by Corey Johnson, really. It's a program to offer half-price MetroCards to low-income New Yorkers. A real way to level the playing field to let lower-income New Yorkers access mass transit so they can access jobs, to really lift-- give them a break.

Brian Lehrer: Happened on his watch, but he can't take credit for it.

Stephen Nessen: Ultimately, he agreed to do it, which was my point. If we're grading him, a C on that, because it happened, but really, he was opposed to it for so long until the very last minute, pretty much. Another thing, like you mentioned, the war of all different ways of getting around the city. As far as biking goes, I would give the mayor pretty-- I know biking advocates would not necessarily say this, but he really increased the number of bikers on the streets, or at least the number of bikers increased on his watch.

Whether bike lanes went in fast enough or plentiful enough or safely enough, and keeping them clear is certainly been an ongoing struggle, but before the mayor took office, there were 380,000 people who took daily bicycle trips in the city. Now it's up to 530,000, and a lot of that is people changing during the pandemic, but it was on an upward trajectory all the same.

Brian Lehrer: Another area that you mentioned in the piece is ferry service, which doesn't get talked about that much. Now my recollection, my conversations with the mayor about ferry service is very expensive per passenger, but he really, really believes in it.

Stephen Nessen: Yes. That's one thing I wanted to look at, especially he talked about it, and the city does sink a lot of money into it. The rider who takes the ferry pays 275, the same as a subway ride.

Brian Lehrer: Expensive for the taxpayer is what I meant. Yes.

Stephen Nessen: Yes. The city is paying $9.73 per trip to subsidize it, which is far more than the subway, how much the MTA would subsidize a subway ride if the actual cost--

Brian Lehrer: Which ones have the most riders, the most usage? Which would you say people appreciate the most, to get around other forms of transportation?

Stephen Nessen: Do you mean, how New Yorkers like to get?

Brian Lehrer: Which ferries?

Stephen Nessen: Oh, I don't have the ridership stats in front of me, but I'm going to guess, in summer, the Rockaway line is by far the most popular. There were lines like down the block and around the corner for hours, people trying to get to the beach in the summertime. I'm sorry, Brian. I don't have the exact numbers in front of me, but I do have some numbers about who rides the ferries.

Brian Lehrer: Okay. Go ahead. Sure.

Stephen Nessen: It took a long time for the city to release the demographic information. I think a lot of reporters at Gothamist kept asking about it, they kept putting it off, and finally came out. It shows that more than half of the riders, according to their surveys are white with a median income of $75,000 to $100,000. Compare that to the average bus rider, the median income is $28,000. When we talk about who is the city for and where's the equity, a lot of money sunk into providing subsidized ferry service, whereas bus service has only gotten progressively slower throughout de Blasio's term.

Brian Lehrer: Let me bring up one other thing which might tie into the question of city subsidies, not necessarily for the people who need the most. What about his BQX streetcar name, nobody desired it for the Brooklyn Queens waterfront, which has no subway lines along it only stops on the way to Manhattan. If you want to do that, north-south or south-north between Brooklyn and Queens, where a lot of people live, a lot of people shop. What was the idea and what happened there?

Stephen Nessen: Oh, wow. You're dragging up some ancient history. There was no real convenient way to connect from Sunset Park, where they have done a lot of redevelopment, but they wanted more redevelopment up to Greenpoint. They were going to do an above-ground like trolley car, basically. I think it was going to be very costly, and I believe, mostly the real estate interests were most interested in it because transit folks were like, "Well, there's this other thing that does the same thing above ground, it's called a bus."

Brian Lehrer: Called a bus. Express bus service.

Stephen Nessen: It doesn't actually cost anything. You just need to clear out some space in the roadway for a dedicated bus lane and you'll get that super fast Queens to Brooklyn service.

Brian Lehrer: It was objected to as a vehicle not just for transportation, but a vehicle for gentrification in areas that were fighting that at the same time. All right, we're going to do one more set of calls. We're going to do the lightning round this time because we're almost out of time in the segment, and we're not going to go A to F programmatically as we did in the last round, we'll go through these lines real quick and see who comes up. Listeners, I'm going to ask you 30 seconds each. Your speed report cards for the Mayor. Anna Maria in Spanish Harlem, you're on WNYC. Hi, Anna Maria.

Anna Maria: Oh, hi. Yes, good morning. Thank you for [unintelligible 00:40:49] my call. Okay, I will give de Blasio a D, but we have lost our liberty of crossing the street or walking around a sidewalk, homeless all over the place. Subway dirty, late garbage, the whole city is a dump now, is garbage all over the place.

Brian Lehrer: What's your letter grade for the Mayor?

Anna Maria: I said D.

Brian Lehrer: D. Anna Maria, thank you very much. Nicole in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Nicole. You're the first person to call with a C, I think it's the nature of talk radio like Twitter. People are going to concentrate on A and on the F spectrum, and people in the middle, they don't call up so much. Why are you giving Mayor de Blasio a C? Nicole in Brooklyn, do we have you? Nicole once, Nicole twice. Paulette in Queens, you're on WNYC. Do we have you, Paulette?

Paulette: Yes. Thanks for taking my call. Good morning. I have a problem with the Mayor and the SOTA Program that he implement because I'm a homeowner and I have property in Connecticut. I took a few of SOTA Program tenants to my property even though I have some which I'm having problem with to get out--

Brian Lehrer: Sorry, say it one more time, what program are you talking about?

Paulette: The SOTA Program, S-O-T-A. The program that he sent them to Jersey, whatever state they want to go. That program that he implement and he said okay. I have some in my property, I had one who move out on my property with five months' rent, she vandalized my property then she abandoned in. I have to fix my property, I lose my five month's rent right now. The one-year program right now they paid me, I actually lost everything. She lived for one year and five months and it's like I get nothing from the government for her because--

Brian Lehrer: Why do you blame the Mayor's policy? You want to connect those dots?

Paulette: You talking to me?

Brian Lehrer: Yes, why do you blame the Mayor, Paulette?

Paulette: Because he is the one who implement the program and then just pay one year and then these people are some people that he knows, they know from the shelter that their people they get problem, but the shelter just give us them and say leave and pay for the year and then the tenant refuse to go and we cannot get anything from the city. We locked out and there's more owner, landlord right now going through the same problem.

Brian Lehrer: Paulette, thank you very much, please call us again. We're going to get Liz's take on that in just a minute. Alison in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Alison. 30 seconds, what's your letter grade for the Mayor?

Alison: I gave him a solid B, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Because?

Alison: B for boy, because first of all, and I did this for your screener and I'm going to really be fast. I follow him on Instagram. I don't know if you do, but most of the comments are so incredibly crude, crass, impolite, disgusting anti-de Blasio, okay. Anyone who gives him a low grade, with all due respect, like the person who just called, the person who was in education, they're selfish. They have a self-centered view of what this mayor should be doing. He is an advocate for everyone, pre-K education. I hope he gets to govern because I raised two girls in the public school system on the Upper East Side. It is gross, it is segregated, and you know who complains - and well I'm not going to say the B-word - the most, are the Upper East Side people who think that they do everything.

Brian Lehrer: Entitled. Allison, thank you very much. Annette in Laurelton, you're on WNYC. Hi, Annette. What's your 30-second letter grade for the Mayor?

Annette: An A-minus. The areas where I am most annoyed with was transportation and unequal tax assessment on homeowners. What I'm very happy with, Mayor de Blasio gave Laurelton and Rosedale, and Cambria Heights, we have a new police station, no other Mayor was able to do it. Roads were upgraded, we have storm sewers that was promised to us. He has really been a plus, in my opinion, for the Laurelton community, except for that transportation and that unequal tax assessment.

Brian Lehrer: Definitely, some of his base was in Southeast Queens, for sure, when you look at who voted for him in large measure in his two elections. One more, Jane in the Bronx, you're on WNYC. I think you're going to be very different from Annette's A-minus from Laurelton. Right, Jane?

Jane: Yes, I am. I'm going to give Mayor de Blasio an F in the area of public safety when it comes to gender-based violence. The Special Victims Division of the NYPD is understaffed, it's undertrained, it's poorly supervised and Mayor de Blasio, we have begged him to address this, it was within his power to address it. Instead what he chose to do was deny that there was ever a problem. When the New York City Department of Investigation documented the problem, he fired the commissioner and the first deputy commissioner who issued the report.

Where does that leave us? Well, about six weeks ago, the New York City Council held a hearing where sexual assault survivors of every race from every neighborhood of New York City testified and they said that the problems continue, the NYPD continues to re-traumatize survivors and fail to thoroughly investigate sexual assault. This is a major public safety issue for women and for every community that is disproportionately affected by sexual assault. I disagree that Mayor de Blasio has been an advocate for everyone. He has not been an advocate for survivors. He's not been an advocate for anyone who's concerned about gender-based violence. In this area, I'm going to give him an F.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much, and not an issue that we probably talk enough about. All right, we're almost out of time in the segment. This is for probably about one more question to our guests "Grading Bill de Blasio." It's part of the kickoff of the series of "Grading Bill de Blasio" articles that WNYC reporters are doing on Gothamist and reporting on WNYC. Our three guests Liz Kim, who reports on mayoral power, Stephen Nessen, transportation reporter and winner of the Congressional Medal for Patience, and Jessica Gould, our education reporter.

Liz, as we go out here, for you, as I guess the most generalist of our group, what do you say to Paulette in Queens, the very unhappy landlord who was talking about the SOTA Program and the effects on her as a landlord, and overall as we go out the door, and you go to the next rounds of this "Grading Bill de Blasio" reporting project, quite an array of grades from our listeners on the phones, and with a lot of passion?

Elizabeth Kim: I can't speak particularly about the successes or failures of that particular program that Paulette talked about, but what I can say just from listening to the callers and also just in talking to New Yorkers, a consistent disappointment or failure that New Yorkers feel belongs to de Blasio that he should be blamed for his on homelessness. I think part of the problem that stems from is the fact that homelessness was not treated as part of his broader housing plan. That is a criticism that housing experts have voiced time and again.

This idea that there's been so much contentiousness over the building of new shelters, the Mayor has been given credit for phasing out the worst kinds of like hotel and cluster sites, but the bigger problem that homeless advocates say that he failed on is he didn't designate or a lot enough housing for people who are the most vulnerable. These are people who are either homeless or they're at risk of becoming homeless. These are considered the lowest-income New Yorkers, and I think the Mayor himself has said that he acknowledged that the income mix was not right during his first term, and he tried to correct that in the second term, but I think housing advocates would say that it wasn't sufficient.

One of the big wins, I think that he had was in 2019, he reached a deal with the City Council to have developers, for developers who receive city funding, they must set aside 15% of their apartment units for homeless New Yorkers. That was a victory, but then again, it was something that he really had to be pushed on. I would say that the callers and New Yorkers as a whole have expressed their unhappiness that homelessness really became this full-blown crisis during his administration.

Brian Lehrer: The article out yesterday Grading De Blasio: Assessing The Mayor's Performance On Education, Housing, and Transportation by Elizabeth Kim, Jessica Gould, and Stephen Nessen. I also, listeners, refer you to Liz's really interesting article that dropped on Gothamist on November 30th, Did De Blasio Make A Dent In The 'Tale of Two Cities'? Thanks for coming on all three of you. Obviously, we'll be looking for your further reporting on this.

Elizabeth Kim: Thanks, Brian.

Stephen Nessen: Thank you.

Jessica Gould: Thank you.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.