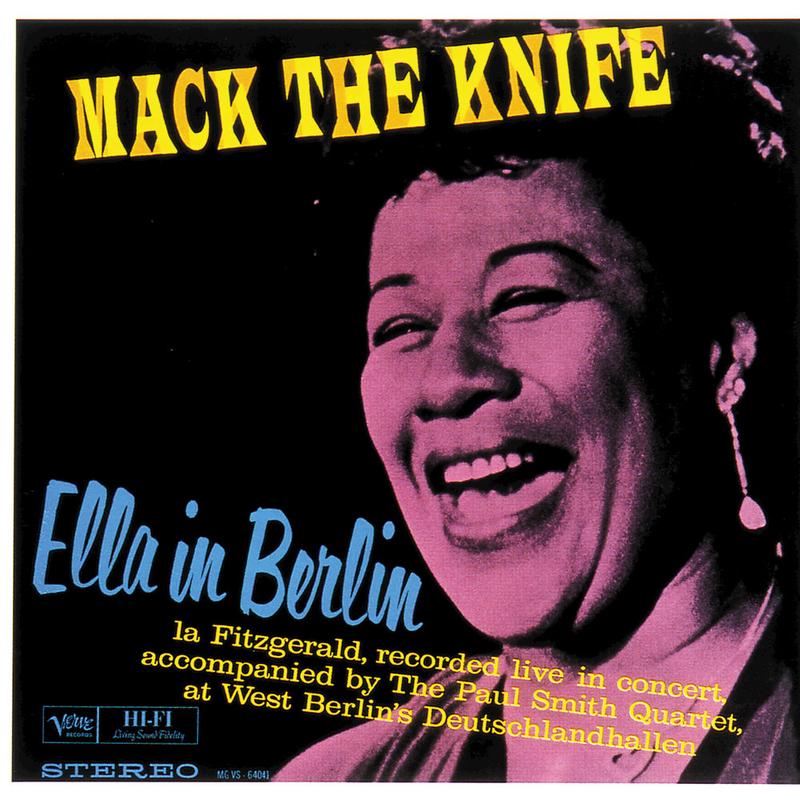

Will Friedwald, author of The Great Jazz and Pop Vocal Albums, is exploring some of the finest recordings of the 20th century on The Jonathan Channel. This week he looks at the Mack the Knife: Ella in Berlin.

Will Friedwald: The idea was that of Norman Granz, who was Ella’s manager and producer, and who was a long-standing supporter of the idea of live recordings, which is something he was trying to do, and starting to do, even in the 78 era. But it really didn't make any sense. What's the point of putting on a live 78 RPM single? It was something that nobody ever thought was a viable thing. But when he heard Jazz at the Philharmonic, his own concerts, and wanted to capture that excitement, he knew there was no way you could just bring those same players into the studio and have them do that. So, he was a believer in the live album, way before the long playing album was even an idea, or even before it was viable. And he realized that with an artist like Ella Fitzgerald or Oscar Peterson, you could just travel around with them and record what they were doing live. Not only was it easier in terms of budget and production, but you could get this kind of excitement that you could not get with a studio project. In the studio you could get perfection, but you could really get this high level of energy on a live recording. So he made a point to record Ella. He recorded her concerts as far back as 1949, which is six years before she left her Decca contract. So, he was sitting on these tapes having this sort of distant belief in the future, and never having any idea that he could ever be able to issue them.

The album that really put it forward for him was this idea of doing Ella in Berlin in 1960. Her 1960 concert tour, [was] driven at that point to a certain degree by the politics of the day. The idea of an American going into the doorstep of the Soviet Union, and that was just the place at the time. And I think that people sort of recognized that this was where the rubber hit the road, so to speak, in terms of the American way of life, was to put it right in the middle of Berlin. And the album was a huge Blockbuster for her. It was, like, one of her most successful albums ever. For one thing, it was a brilliant performance, but at the same time they really liked this idea, that this most American of musics, jazz, was being performed right at the doorstep of the Nazis and the Soviets, right in the heart of Berlin.

It was a total coincidence that they chose "Mack the Knife" as the centerpiece for the album, because I do not think Ella was really thinking about the fact that "Mack the Knife" had originated in a German show in Berlin. In fact, in the 1927 show Die Dreigroschenoper. As far as Ella was concerned, it was just this other show tune and it was just another hit. The first guy to do it in a jazz context, or a popular context, was Louis Armstrong, famously. And then Bobby Darren based his version on Louis's, his own take on pops. And then it was enough in the zeitgeist, you should forgive the use of a German word, that Ella just wanted to do it, but she wasn’t necessarily thinking about it as a German song at all.

Fran Morris Rosman, who runs the Ella Foundation, and knew Ella very well, says that Ella’s vanity, if that’s the right word for it, was such that she did not want to wear her glasses on stage and hold the lyrics sheet in front of her. She just thought that was bad "show business" to be looking at a lyric sheet, particularly because her vision was so bad and she required these really huge, thick horn-rimmed glasses. And it wasn't until the 1970s that Ella relaxed to the point where she felt comfortable wearing her glasses on stage, so the story that Ella completely forgot the words is totally believable, and she starts making up her own lyrics in the middle of it. And pretty much they’re just as good or they’re just as relevant as the original lyric by Bertolt Brecht, which is really something that is specific to the show. For Ella just to trash the words and make up her own is perfectly appropriate, and it's telling that it was not planned that she would launch into her own lyrics, because when she did the song in the future, and she did on several other occasions, she gets the words right. So she only allowed herself that one time to screw up, and never repeated it.

I always liked the way she did "Lorelei," which is a song by The Gershwin brothers, and it’s another song of strangely Germanic origins that she was not necessarily conscious of. It’s from a show called Pardon My English, which was this whimsical, satirical show that the Gershwins wrote in 1934. I believe it was not a hit, not as successful as Of Thee I Sing. But it's set in Berlin in 1934, and it’s way too whimsical and capricious to talk about Nazi Germany or anything like that. It's this funny idea of a nightclub in Berlin, and the Lorelei is a character from German mythology that the Gershwins decided to work into the song, set in a show in a German nightclub. That's why there's all these references to the Rhine, and in the bridge when Ella was sings “Ya, ya.” And she really gets off on the idea of singing about this legendary siren, like Circe from The Odyssey, that's what these Lorelei's are. And she really gets off on that idea, really seems to enjoy presenting herself as somebody who's so funny and sexy at the same time. She talks about doing a striptease in the middle of it, quite, very funny stuff. Ella had this great wicked, wonderful sense of humor that I think comes to the fore in songs like these.

"The Lady is a Tramp," it's another song that became a huge, huge standard from the fifties on, but for almost 20 years hardly anybody did it. And then in ‘56 and ‘57 Mel Torme, Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra all did it within a few months of each other and it became one of the all-time signatures of the Great American Songbook very, very quickly. And it's one of the songs that is a career signature for both Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald. Ella’s was on the Rodgers & Hart songbook, which came out at the end of 1956, and she did the verse. Then, she always kept that in her interpretation, as opposed to Sinatra who rarely ever sang verses, but it's a song that’s really associated with both of them. And they both have their own approach to a lyric that Lorenz Hart intended as something very ironic. It doesn’t literally mean the “lady is a tramp,” in either the sexual sense, or the social sense, of a tramp as, like, a homeless person, either way like that. He just means it's because this lady is unconventional, that other people might regard her as a tramp, in either sense you could say, so it's a very ironic meaning. And I think that, again, it shows an intelligence that not enough people give credit to Ella for having, that she could do a song with such an ironic meaning and have the meaning be absolutely, crystal clear on multiple levels. And that's the sort of thing we associate with Sinatra, and rightfully so, but I don't think Ella gets enough credit for it, because she actually does a brilliant job with it.