Donovan Drayton was arrested and accused of murder days after a 30-year-old man’s bullet-riddled body was found in the doorway of a single-family home in South Jamaica Queens.

Drayton, a 19-year-old with no criminal record, said he was innocent. But given the severity of the charges, a judge refused to grant bail. So he was sent to Rikers Island pending trial. And there he waited.

And waited.

Drayton spent five years behind bars as a pretrial detainee. In July he was acquitted of murder. His case is the story of a court system so plagued by delays that the notion of innocent until proven guilty has been turned on its head.

Over the past decade, as New York City’s backlog of felony cases has grown, so too has the time defendants are spending behind bars before trial. The average pretrial detention in a felony case was 95 days in 2012 — up 25 percent from a decade earlier, despite a drop in new felony cases, according to a recent report from City University of New York researchers. And some defendants spend significantly longer behind bars. Of the people who spent time in jail during 2012, about 3,200 were behind bars for a year or more awaiting their day in court, according to city data.

“It’s contrary to the idea of justice,” said Jonathan Lippman, the Chief Judge of the State of New York. “Delay in trial is bad. We have to find ways — particularly when you have these issues of whether people are incarcerated or not — to resolve these cases more quickly.”

From 2000 to 2012, the number of felony cases pending more than 180 days doubled even as the number of new filings dropped by a quarter, according to the city’s most recent Criminal Justice Indicator Report. The New York Times spent a year investigating delays in the Bronx courts – the slowest of the slow.

Lippman, who oversees the state court system, has succeeded in reducing the backlog of felony cases considerably. But still, as of mid-June, 55 percent of felony cases citywide were more than half a year old. Currently, there are about 1,500 people who have been in jail for at least a year awaiting trial, according to corrections data.

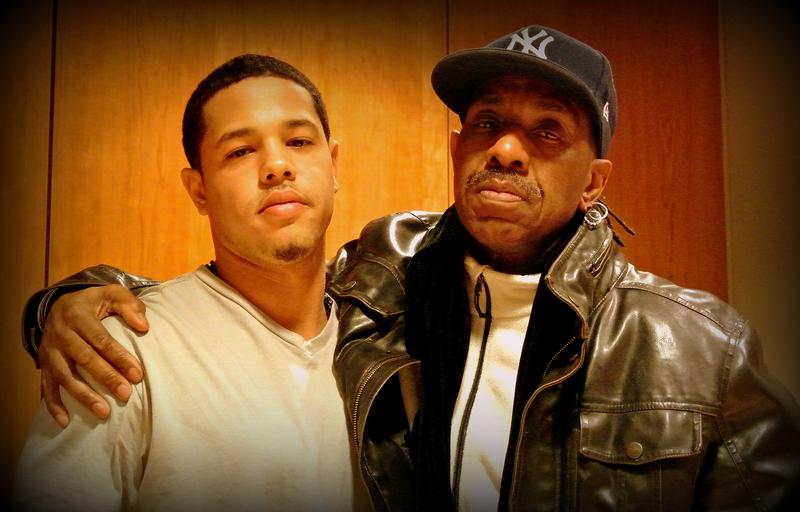

Ronny Drayton, Donovan’s father, struggled to explain what it’s like as a parent to fight a case for so long.

“You know there’s really no words to describe how you feel when somebody is trying to take your child from you, man,” he said in July on his way to the Queens Supreme Court, a building he’s been coming to for almost six years.

Donovan’s story

Donovan Drayton, now 25, says that on Oct. 1, 2007, he got a call from a couple of older boys he knew casually from his Queens neighborhood. They wanted to buy marijuana. Donovan admits that he sold a little from time to time.

He said went for a ride with the two, thinking he’d make a little money and smoke a little on the way. In an interview, he said he had no idea the two men, both in a gang, planned to rob a drug dealer.

That robbery went bad when the dealer grabbed an assault rifle. Bullets flew. Donovan said one of the guys he was with tossed him a gun. He said he fired once in the air and fled from the scene. In the chaos, a friend of the drug dealer’s was shot five times and killed.

Detectives investigating the case quickly came to believe Donovan helped plan the robbery and was one of the gunmen. He was arrested Oct. 12, less than two weeks after the killing.

It would be almost four years before Donovan’s lawyers got a chance to argue his case before a jury. He spent that entire time locked up on Rikers Island.

His current attorney, Michael Warren, thinks the prosecutor deliberately delayed the case to get Donovan to take a plea deal.

“Some of the prosecutors feel that if a person is in jail long enough they will, as they say, cop a plea,” Warren said. “That settles the case and that eliminates the burden of the prosecutor having to prove beyond a reasonable doubt in some situations very difficult facts.”

The Queens District Attorney’s Office declined multiple interview requests. In a Village Voice article about the case, a DA's spokesman was quoted defending his office's handling of the case and blaming the defense for more recent lags.

If delay was the prosecutors' strategy, Donovan said it almost worked. After he'd spent three years behind bars, a judge outlined the stark reality: Donovan could face life in prison if he didn’t take the 18-year deal prosecutors then were offering.

“He put the full court press on me,” Drayton said, adding that the judge almost scared him into taking the deal.

But he wasn’t fighting alone. His father Ronny is a guitarist who has played with the likes of the Chambers Brothers. The elder Drayton put the same sweat-pouring energy he has on stage into saving his son.

“Almost all my waking moments are focused on this,” he said in an interview.

Ronny sold his guitars, hit up friends for money and scraped together enough to fund a legal team. The case went to trial in June 2011, and Donovan was acquitted of a murder count, manslaughter and possession of the murder weapon.

But the jury was hung on several other counts, with 10 of 12 in favor of acquittal, according to Donovan’s attorneys.

The DA’s office decided to retry Donovan on the outstanding charges. A judge once again refused to grant bail, despite the partial acquittal, Donovan’s clean record and the fact he had a strong community of supporters. So he went back to Rikers awaiting a second trial.

Back to jail

Rikers Island almost broke Donovan. The daily violence. The boredom. The fear that he might spend the rest of his life in jail. One day, he was about to call his dad when he looked out the window over the East River at the city and it hit home.

“It’s a possibility this might be it for me,” Donovan said, recalling his feelings that day. “I might never drive on that highway again. I might never cross this bridge again. I might never get to see this building and stand in front of this building again. I might never get to see Manhattan again. I might never see none of this again.”

But his dad wasn’t about to give up. Ronny Drayton fought even harder, tapping into a community of artists and performers to help raise funds for the mounting legal bills. They put out a benefit CD and held two benefit concerts at the Highline Ballroom featuring Living Colour and other bands.

They got a break last fall when Warren, one of the city’s top defense attorneys, and his wife Evelyn, also a defense lawyer, agreed to take the case and handle the second trial. Michael Warren was lead counsel on efforts to free the Central Park Five. He’s represented the likes of rapper Tupac Shakur. And he’s sat on international tribunals.

The first thing Warren did was file a writ of habeas corpus with the appellate court calling Donovan’s detention unconstitutional. Four justices heard his argument and ultimately agreed.

The court set bail at $125,000. Donovan bailed out on October 24, 2012 — five years and 12 days after his arrest.

With Donovan free, Warren went to work. During a two-week trial he punched through all the weak spots in the DA’s case. It turned out there were a lot. There was little physical evidence. Police didn’t do a full forensic investigation. And the two witnesses who testified against Donovan — the getaway driver and the drug dealer — got sweetheart deals for their cooperation and came off as liars.

In late July the second jury started deliberations. They were back in a matter of hours.

Donovan was acquitted of all but one count of weapons possession.

It’s not nothing. It’s a felony and could carry more time behind bars. But given his clean record, there’s a good chance he’ll get off with time served.

Donovan is scheduled to be sentenced Wednesday on the weapons count.