Harlem is one of the worst places in the city to spend the summer.

Sure, it's got a few Olympic-sized swimming pools, midnight basketball games and a lively picnicking culture. But consider this:

- Harlem has a high concentration of brick, concrete and asphalt, all of which conspire to trap heat during the day and keep nighttime temperatures high;

- Environmental and social characteristics put Central Harlem onto the city's list of the top 10 neighborhoods in terms of "Heat Vulnerability;"

- In East Harlem, about a quarter of seniors don't have air conditioning in their homes, the fifth highest rate in the city;

- Twice as many people from Central Harlem visit the emergency room for heat stress each year compared to the rest of the city, when the number is adjusted to take into account age and population.

Those are some of the reasons why this summer, WNYC, along with the AdaptNY news service and the ISeeChange weather journal, are joining together to document how hot it gets inside those apartments that aren't air-conditioned.

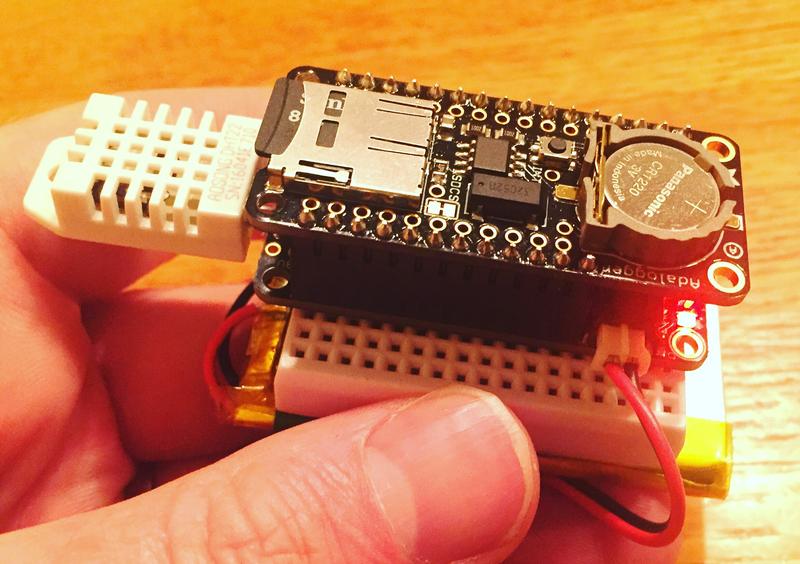

And by "document," we don't just mean record through audio stories on WNYC and Harlem community radio WHCR. Or the type of personal climate reflections that ISeeChange is known for — though that too. We mean that we will put sensors into people's homes that will monitor the temperature and humidity, morning, day and night.

And to help us get access to people's homes, the project has joined up with a community organization, WE ACT for Environmental Justice, that has recruited volunteers who will serve as "ambassadors" to install these sensors into apartments belonging to friends and relatives.

"The idea is that these volunteers, these ambassadors, will come and visit folks once a week, maybe twice a week, and get the data off the sensors and also just check in on people," said John Keefe, WNYC's senior editor for Data News.

Scientists have long known about the "heat island effect" or "urban heat island" — how cities tend to be a few degrees warmer than surrounding suburbs or countryside because of the way buildings and pavement trap heat. And some experts — including Brian Vant-Hull, a researcher at City College who is also helping to conduct the Harlem Heat Project — have mapped out how different neighborhoods are warmer or cooler depending on their elevation, proximity to water, or amount of greenery.

But that research is generally based on outdoor readings.

"One of the ways people measure heat is just having sensors outside," said Prathap Ramamurthy, an assistant professor at City College of New York, who is an informal scientific adviser on the project. "The great thing about this project is that we are going to measure how people inherently feel these heat waves," meaning, how they live with heat indoors.

In the end, after the data is collected, downloaded and analyzed, and the stories are told and heard, the partners will convene a meeting in the fall, during which community members will discuss what can be done to mitigate heat illness in Harlem, especially as global warming is expected to increase average temperatures in the region by as much as 5 degrees Fahrenheit as soon as the 2050s.