Click the player above to hear our story about a renewed effort to better integrate schools in one part of Manhattan. Click here to see how new admissions rules could change where students in District 1 go to school.

It's no secret that the New York City public schools are deeply segregated. Throughout the five boroughs, most black and Latino students attend schools where they are the overwhelming majority, according to both a much-cited 2014 UCLA study and more current city data. Beyond the social implications of racial and ethnic segregation, there is inequity: most of the predominantly black and Latino schools have high concentrations of low-income students, fewer highly qualified teachers and lower test scores.

In recent years, pockets of New Yorkers have proposed new solutions to counteract the divides that have gotten worse in the last decade. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio on Friday told WNYC's Brian Lehrer that he wanted a more integrated system.

"I think we finally have the tools we need to do this on a much more extensive level,” he said.

It seems to be a moment when elected officials, educators and families are looking to do things differently in New York, perhaps the most concerted school integration effort since the 1960s. In our week-long series Integration 2.0, we highlight a proposal to better mix students within one school district, visit a school that's taking extra steps to recruit and support a variety of families, hear from New Yorkers who participated in integration experiments in 1964; they have some thoughts worth hearing.

And, finally, we'll share another point of view: integration is not a goal unto itself for many New Yorkers who overwhelmingly say they want better school options in their neighborhoods. Period. For some, integration is a path towards school improvement but not for all.

Of the ideas concerned with changing school admission rules, the most ambitious involves an entire school district, District 1, which includes the East Village, part of Chinatown and the Lower East Side. And that's where our series begins.

Parent leaders in District 1 are hoping to win approval from Schools Chancellor Carmen Fariña to try a new form of admissions. Their goal is to prevent schools from enrolling too many poor and at-risk children, by bringing in kids from higher income levels, too. Various studies have shown kids from low-income families do better academically when they're mixed with wealthier peers.

To accomplish this, District 1 has proposed an admissions system called controlled choice that's still being finalized. It's been used in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as well as other cities around the country. Parents rank their preferred schools. The city would then consider whether their children qualify for free or reduced priced lunch when assigning incoming kindergarten students to every school.

In District 1, where about three quarters of the students qualify for free lunch, this means every school would aim for a similar proportion of new kindergarten students. By distributing students more evenly, supporters believe there would also be greater racial diversity, and maybe more involved parents, more funds and more stability in the teaching staff wold follow. In other words, the schools would get better.

For more on how it would actually work, check out these charts and images.

Parent leaders and schools are still in talks with the Department of Education about the controlled choice plan. “Officials are having fruitful conversations as details about the proposal are being still worked through,” said department spokeswoman Devora Kaye.

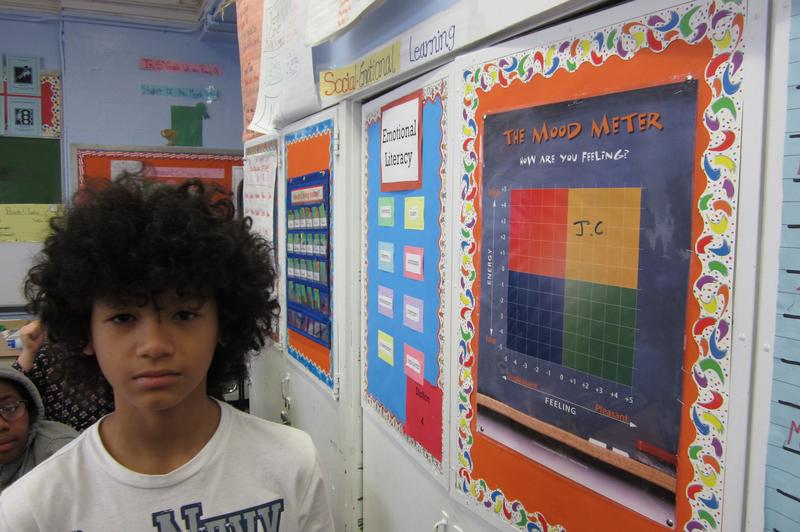

The Roberto Clemente School, P.S. 15, is one school that could potentially benefit from this change. It's cheerful and inviting. Every hallway of this century-old building in the East Village is lined with murals, photos of smiling children and student drawings.

But the tiny school is what educators call "extremely segregated." Almost all of its 161 students come from very low income families. This year, 39 percent of them are homeless or in transitional housing.

Principal Irene Sanchez said that has a negative effect on pupils.

"When we talk about student learning and diversity, we talk about students learning from each other," she explained. But when nearly all of the students are coping with the stresses and crises associated with poverty, she said, it's much harder to create a balanced classroom where children can learn from each other.

Currently half the roughly 5700 elementary students in District 1 are Latino, followed by Asians, blacks and whites. Out of the 17 schools with elementary grades, most are 80% black and Latino and 80% low-income. But five have a disproportionately higher percentage of white and wealthier students. They also tend to have higher test scores and are extremely sought-after.

This de facto segregation is widely blamed on the current system of school choice. Former Mayor Michael Bloomberg made it easier for families to apply to various schools. In District 1, which already had a similar policy, principals used to consider race in their admissions process to achieve a balanced mix. But that came to a halt in 2007 after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling. Since then, a study commissioned by District 1 parent leaders found school segregation has gotten worse.

School choice also favors savvy, educated parents, who apply for the schools they like and shun those with lower test scores, or more at-risk kids like P.S. 15. Other families choose the ones that are most convenient; or they don't even know about their myriad options.

"The choice system in New York City, now as far as I can see, is pretty much an end in itself," said Michael Alves, who designs school admissions systems around the country. Alves helped create the controlled choice system in Cambridge more than 30 years ago and he said it ensures a more level playing field.

In Cambridge, which is smaller than District 1, about 30 percent of pupils qualify for free lunch. The district's algorithm is set so that 38 percent of new kindergarten students in each school qualify for free lunch, plus or minus 10 percentage points. Some schools still wind up with more than that, because of the choices families make.

Linh O, director of registration and enrollment, said about 10 percent of families don't get their top-choice schools. When that happens, the district assigns them to a less popular school. Some reject it and leave, but O described one elementary school that's picking up momentum.

"What I've seen in the last three years is that once we have parents actually try the school out, they actually really like it," she said.