NYPR Archives & Preservation

NYPR Archives & Preservation

How Irish Tape Saved Civilization

Besides Scotch tape of the sticky kind, those in the audio world know about Scotch audio tape. But what about Irish brand tape? Turns out that its creator, John Herbert Orr, survived a land mine and near financial ruin in order to pursue his dream: to bring audio tape technology to the United States.

It all started on a fateful day in late spring 1945, when thirty-five American and British men, most of whom worked in war intelligence or propaganda, gathered in the studios of Radio Luxembourg. The station, which during the war had been one of the most powerful stations in Europe, had recently been captured from German hands; but the retreating army had willfully destroyed much of the facilities. As a consequence it had taken a team of Allied engineers a few months to rebuild the station, during which they had learned firsthand about advances in German technology —advances which had, until then, been hidden behind enemy lines. But nothing had prepared the thirty-five men present for what they witnessed that day: the incredible sound of a rebuilt German Magnetophon, or tape recorder, playing back audio that was virtually indistinguishable from the original, with a lifelike presence far beyond what American and British recording technology had achieved at the time.

Among the seventeen engineers present at that demonstration was John Herbert Orr, a son of Alabama farmers whose passion for radio and electronics had led him, through a tortuous path, to work for the Anglo-American Psychological Warfare Division. For Orr, the demonstration only confirmed his suspicion that Adolf Hitler’s speeches were often not broadcast live, but recorded using this technology. (Orr, charged with tracking Hitler’s movements, had been puzzled at the speed with which the Nazi leader had seemingly moved from the location of one broadcast speech to another.) He had learned about German tape recording technology the previous year, and had strongly suspected that this was the answer. Now he was certain, and he became obsessed with the technology.

A spectacular blunder gave Orr the opportunity to put his obsession to work. Radio engineers at Radio Luxembourg, who often re-used the plentiful stock of audio tape from the studios, were broadcasting a pre-recorded speech by Eisenhower when suddenly the general’s voice faded and instead an animated voice took over the airwaves –the sound of a previously recorded speech by the Führer, once again broadcast over the most powerful station in central Europe. This went on for several minutes before the engineers realized their gaffe; Eisenhower, none too pleased, issued an order that only new tape be used for broadcasting. Orr was the logical man to be put in charge of re-starting tape manufacturing, and consequently he traveled around occupied Germany learning all about the technology from local engineers. –especially BASF’s Karl Pfaulmer, with whom he became friends.

During one of these research trips, Orr almost lost his life when his Jeep hit a land mine. But the accident brought an unexpected result: while recuperating in a hospital, Pfaulmer gave Orr his version of the philosopher’s stone —all the known formulas for tape manufacturing, contained in a small envelope.

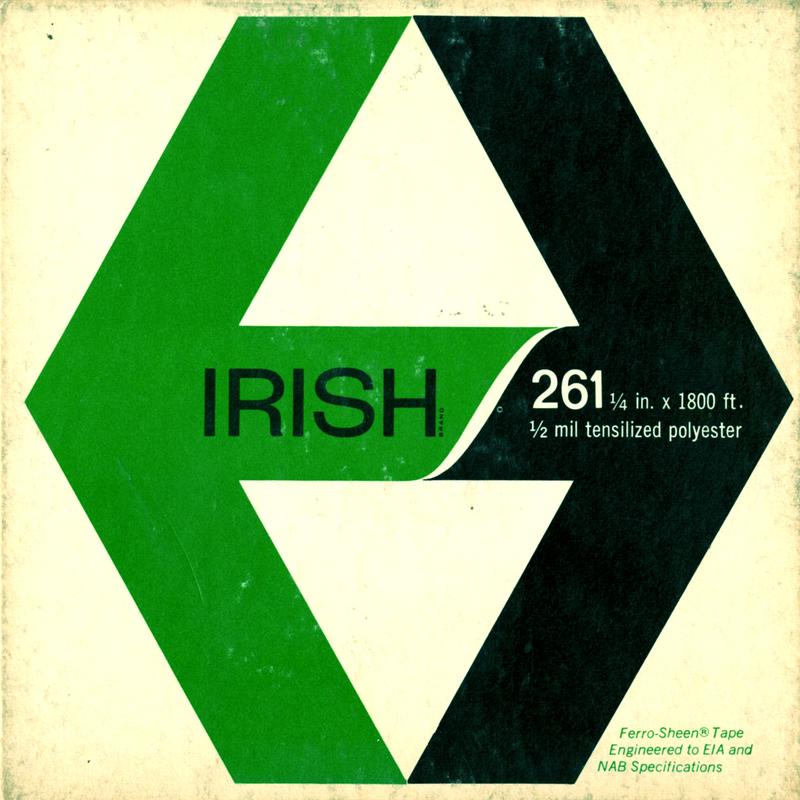

Armed with all this knowledge (and some machines), John Hebert Orr returned to Alabama in late 1945 and continued to experiment with tape manufacturing. Four years later he founded OrRadio and started selling Irish brand audio tape (The name incited controversy for its perceived parallels with 3M’s Scotch tape, but Orr always claimed it sprung from an Irish nurse, Molly, he befriended while at hospital). Orr's nascent company was plagued by technical and financial difficulties for years, but the years 1952-53 proved to be a turning point. In 1952 he hired engineer Herbert Hard, who two years later developed the “Ferro-Sheen” process.

Thanks to this process, which involves heating the tape during manufacturing (during his experiments, Hard ruined at least one of his wife’s irons), Irish brand tape became 60 years ago one of the world’s finest. But Orr knew that technical advances were only part of the equation: he also hired Nathaniel Welch, who designed clever advertising campaigns (including the leprechaun F. R. O’Sheen) and focused on the home “hi-fi” market. Swiftly, sales went up 307% in two years, and OrRadio became an established competitor to manufacturing giants 3M and Ampex. Orr’s dream had finally come true.

For the rest of the twentieth century, the magnetic recording industry would blossom into what we have today —a world of data tape, massive servers and solid state cards (one of Orr's original designs was a primitive magnetic disk very much like today's hard drives). Orr would later claim that the men who developed this entire industry in the U.S. were all —to a man— at that fateful presentation in 1945. As for Orr himself, in 1960 Ampex bought his company, and he went on to pursue other technologies (including early prototypes of the 8-track). An industrial park in Opelika, Ala., is named after him –and the colorful designs of his tape boxes live on in innumerable collections.

You can hear above some Irish tape being put through its paces in a recording of a 1957 concert by WNYC’s David Randolph of Bach’s B-minor Mass–definitely some oversaturation and dropouts going on, but not bad!