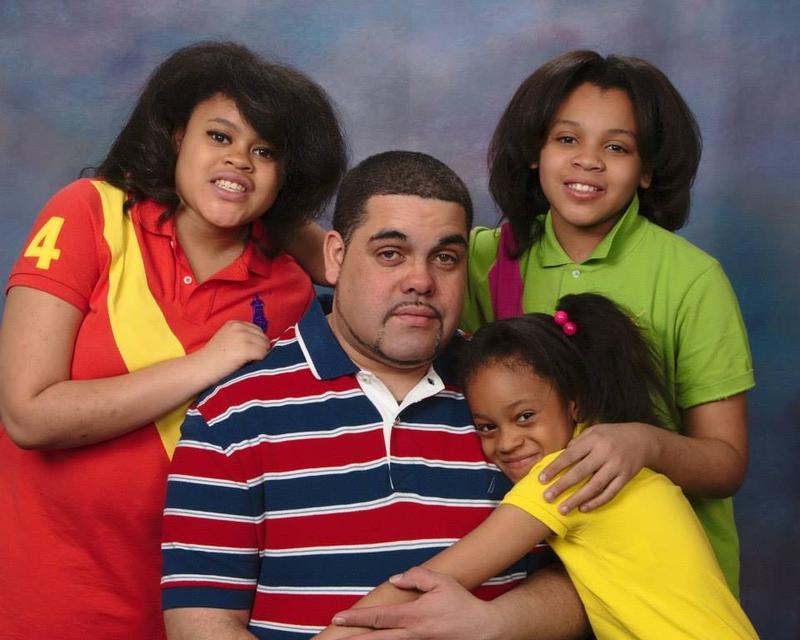

It was dinnertime on May 21, 2014 when Danny Cruz began suffering from a severe asthma attack while at home with his wife and three daughters in a ground floor apartment at the Red Hook East Houses in Brooklyn.

His family called 911 for an ambulance — twice. His wife Tynisha Cruz placed the first call at 7:47 p.m., according to an event chronology report. In a recording of the 911 call, Cruz told the 911 operator the family’s address, and said her husband was having an asthma attack. The 911 operator tried to connect Cruz with someone from Emergency Medical Services, standard protocol for the city’s 911 system. But no one answered after six rings.

Still on the line, the 911 operator took down Danny’s age, 40, and assured Cruz, “assistance will be there as soon as possible.”

After four and half minutes, when the family heard no sirens or other signs that assistance was on the way, Cruz ran out into the courtyard to flag down any help she could find. Her twin sister, Lythisa Rogers, stayed inside to make a second call to 911. This time, she was connected to EMS. She told the operator that Danny was turning blue. For nearly eight minutes, she frantically tried to give her brother-in-law CPR.

Approximately 12 and-a-half minutes after the first 911 call, the EMS operator finally said the ambulance has arrived. By that point, Cruz had already come back with two police officers. She says a fire engine also showed up along with two ambulances. They took Danny to the hospital, where he died after nearly two weeks on life support.

The Cruz case is a worst-case scenario. But it raises the question: How long should someone have to wait when the city says assistance is on the way?

In 2014, EMS responded to 1.3 million medical emergencies, including 483,000 life threatening calls like this one. Today, the response time for life-threatening medical emergencies is slower than it is for any other high priority call, including police and fire emergencies.

Part of the reason for those delays can be traced back to a merger that combined EMS with the fire department nearly twenty years ago.

The merger started as the brainchild of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, who announced it in his 1995 State of the City address. He said firefighters would become first responders to speed help to victims of medical emergencies.

“Because fire houses are strategically located throughout the entire city, response time when you use the fire department as the first responder is cut more than in half,” Giuliani pledged.

Back then, he said response time to serious medical emergencies was about 8 minutes. The goal was to bring it down to 6. The city has never hit that target. Today, under a new formula that includes the 911 call processing and dispatch time, it’s over 9 minutes.

The number of medical calls has steadily increased over the last twenty years, as the city’s population has grown and aged. It’s changed the nature of work for the fire department. But the agency has been too slow to integrate EMS, according to a report released Wednesday from the Citizens Budget Commission.

“Seventy-five percent of the incidents they deal with are medical emergencies,” said Charles Brecher, the co-director of research for the CBC. Fires are a much smaller part of their work, Brecher said. “It’s about 5 percent of all the incidents they deal with and that’s declining.”

Still, the CBC also found that fire operations make up almost three quarters of the FDNY’s $3.8 billion budget, while only 13 percent goes to EMS.

There are lots of reasons fire takes a bigger portion of the pie.

“Fire equipment is more expensive, there are many more fire houses than there are ambulance stations,” said Brecher. “We’ve got a big sunk cost in the firefighting side of the operation.”

According to the FDNY’s vital statistics for calendar year 2014, there were nearly three times the number of uniformed fire personnel compared with EMS. Salaries on the fire side are also substantially higher.

But the problem is not just dollars and cents. It’s rooted in how the agency came together two decades ago. Former Fire Commissioner Tom Von Essen, a one-time head of the firefighters union appointed by Mayor Giuliani at the time of the merger, said there were cultural differences from the start.

“The idea of merging is to make people equal. Maybe not immediately, but that’s the goal,” said Von Essen. “I don’t think that’s ever happened with EMS.”

He suggests significantly boosting the medical training for firefighters to the level of a paramedic.

“If we had a larger pool of paramedics and we’re able to get them out on more calls, we’d be saving more lives,” Von Essen said, while also acknowledging that such a move would come with a hefty price tag.

The CBC also recommends more medical training for firefighters, to the EMT level. It’s a step below paramedic, but they can still handle more serious medical calls, a standard practice in cities like Chicago, Houston and Phoneix.

Currently, firefighters assigned to the city’s 198 engine companies do respond to medical emergencies, and they often arrive faster than ambulances. But there are limits to what they can do with their skills and equipment.

During their 18 weeks at the fire academy, firefighters complete 80 hours of medical training. EMT’s are required to complete 200 hours of training and receive state certification. Paramedics complete 1,280 hours of training, six times the amount of an EMT, along with state certification and field work.

But John Perrugia, EMS chief from 2004 through 2011, says more medical training for firefighters is the wrong way to address the increased number of medical calls. He says the agency should put more money into EMS.

“If my house is on fire, I want the New York City Fire Department there. If I'm having a heart attack, I want New York City paramedics,” said Perrugia, who now teaches Emergency Management at the Metropolitan College of New York. “I don't want a firefighter who sometimes does medical calls to come help me.”

The de Blasio administration added $18 million to increase ambulance tours and emergency medical dispatchers this year.

That was too late for the Cruz family, which is now suing the city.

“I don’t think that’s fair,” Cruz told WNYC earlier this summer. “Because if I called twice, how come it took forever for them to show up?”

The fire department would not comment on the case because of pending litigation.

The agency has made better integration of its Fire and EMS services a goal in its 2015-2017 strategic plan. That includes looking at the potential of having ladder companies respond to medical calls and possibly training some firefighters as EMTs.

At the family’s apartment, Cruz still keeps signs of Danny around. She uses his cell phone, which still has Danny’s greeting on the voice mail. His favorite baseball and hockey jerseys hang in their closet. She says she keeps expecting him to walk through the door.

“I don’t know when I’ll be able to move on,” said Cruz, “because I wasn’t expecting to be a widow at 39.”