Ian Karmel On His Memoir, 'T-Shirt Swim Club'

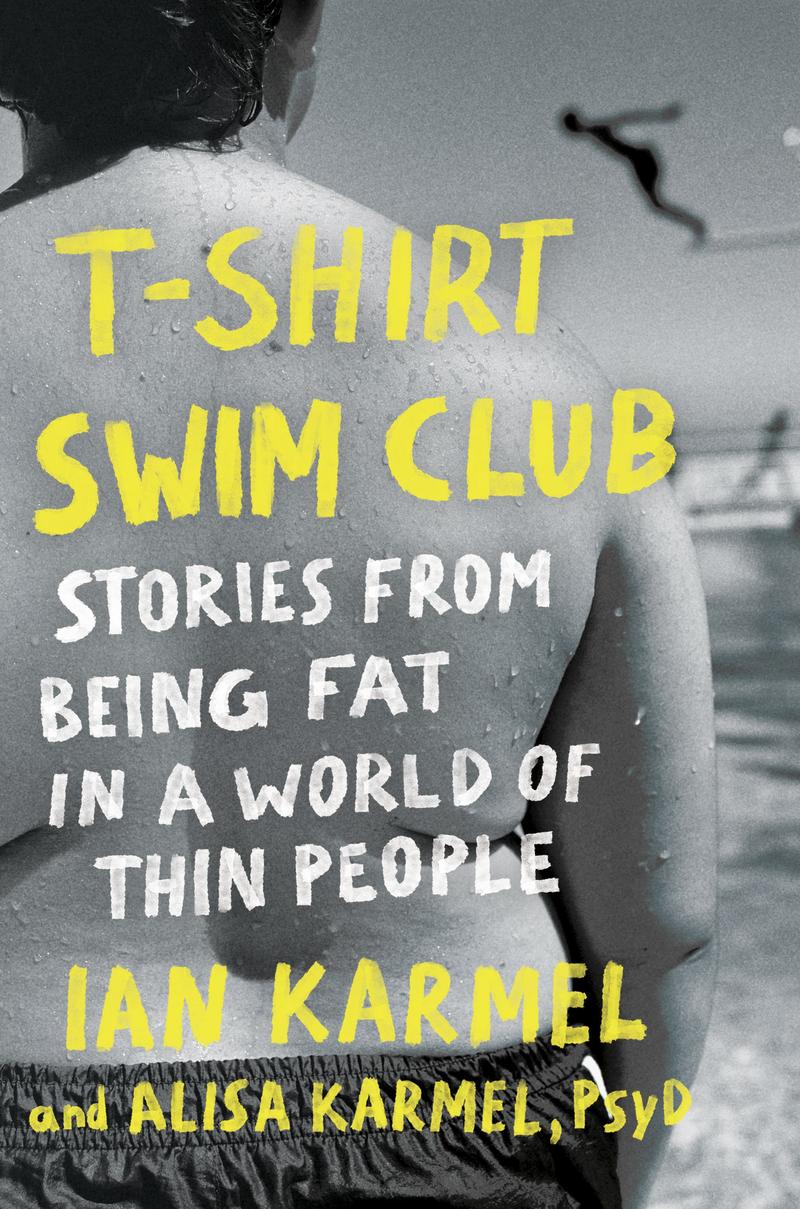

( Courtesy of Penguin Random House )

[REBROADCAST FROM June 11, 2024] Comedian Ian Karmel and his sister, Dr. Alisa Karmel, grew up overweight as kids. However, they never talked about it. In a new memoir, the two reflect on their childhood experiences. Ian joins us to discuss their book, T-Shirt Swim Club, which is out today.

This segment is guest-hosted by Kousha Navidar

[music]

Alison Stewart: You're listening to All of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. As summer comes to a close and a few members of our team are enjoying the last few sunny days by taking time off. We are presenting a few encore conversations called Producer's Picks. Today, producer L. Malik Anderson introduces us to one of their favorite conversations of the summer. It's a candid, funny, and heartfelt collection of stories that comedian Ian Carmel wrote about being fat while growing up. Here's Malik.

- Malik Anderson: Emmy-nominated comedian, writer, and actor Ian Carmel's new memoir is titled T-Shirt Swim Club: Stories from Being Fat and a World of Thin People. In the introduction, he makes it clear that this is not a weight loss book. Instead, he provides a candid reflection of his childhood swimming with and without a shirt, doctor's visits as a kid, high school popularity, and shopping for clothes. Ian joined guest host Kousha Navidar on All of It to discuss the memoir on publication day about two months ago. I remember vividly how open, honest, and excited he was to talk about his experiences. I was surprised he had the energy considering the fact he and his publicist had just run down the street from another interview. Then we had to rush him into the studio to get him seated, a minute to spare before going live. I was pretty anxious, but luckily, the adrenaline kicked in, and it turned out to be a hilarious interview. We also took your calls and questions, but since this is an encore presentation, sadly, we cannot take your calls live. Let's listen to part of the interview.

Kousha Navidar: First thing that I thought of when I looked at it was t-shirts, pools. That is a very interesting title. Can you tell us about that title a little bit?

Ian Carmel: Yes, now, I think people wear t-shirts in the pool to protect themselves from the constant assassination attempts of the sun, right? That's become a more universal thing, but for a very long time, a t-shirt in a pool was a feeling known almost exclusively by fat kids. It was a thing we did when we were little, and we found out we were fat. We wanted to somehow obscure or cover up that fact that we were fat and that we were supposed to be ashamed of our bodies by putting on a t-shirt and then getting it wet, which is absurd as much as it is sad because it would suck to your torso, right? It would accentuate, if anything, your curves.

Like, I spent my entire childhood in pools as a kid, with still my fat body, but just through a wet Big Dog t-shirt. I thought that anyone who had also been a fat kid would immediately know the sensation of wearing a t-shirt in a pool.

Kousha Navidar: It's interesting to see your career as both a stand-up comedian and a writer for late-night, now doing a memoir, which is a different form of writing. First, what inspired you to write the book, and then second, what was the process like for you to try this new medium?

Ian Carmel: Yes, the inspiration for the book. I was talking to my little sister, who has a doctorate in psychology and works in nutrition and who was also a fat kid. I had gotten myself to a weight where I was healthier. She had done the same thing. We were looking back on that process, and we'd realized we'd never spoken to each other about our experiences being fat kids. I think when you're a kid, it's hard to talk about. It's hard to put those feelings into words. Then as you get older, it's like you're in a hurricane, right, and it's hard to talk about. You're like, "Boy, the wind is really strong." No, you're like nailing boards to windows, right, and running into the basement to get away from it.

Kousha Navidar: Sure.

Ian Carmel: We finally got a little bit of distance from it. We were looking back, and she dealt with being a fat kid by getting a doctorate in psychology. I dealt with it by doing the opposite, getting into comedy. We thought, I think we have two really good perspectives here. I think there's a lot of things we're talking about right now that we haven't seen written down before, and especially, there's been some amazing books by women about the experience of being fat. Roxanne Gay, Lindy West, so many people. From the male perspective, there hadn't been as many and it's because men, I think, we're told not to indulge those feelings. We're told to toughen up.

I know that I dealt with being fat by either joking about it or being sad alone and not telling anyone else because it was bad enough feeling different because of my body. I didn't then want to start complaining about it around other people and give them another reason in my head not to like me. That's isolating and it makes you feel alone. It makes you feel lonely, even more depressed. When you already deal with those feelings by eating-- which is what I did, and eventually drinking and doing drugs and all sorts of other things where I could continue to seek comfort- I think those feelings can be really dangerous.

We thought in a way that is funny and empathetic, hopefully, coming for me, and in a way that is very knowledgeable and empathetic, coming from my sister, who literally deals with patients about this kind of thing. We thought it would be a really good way to talk about this stuff and tell that story and hopefully help some people. At the very least, make them laugh.

Kousha Navidar: That gender piece that you're talking about is so interesting. Can you go into that a little bit? What was it like for you thinking about 'here is what is missing in this gap among people, maybe specifically people who identify as male, as being overweight. What's the role that I can fill in there?'

Ian Carmel: I mean, I definitely did. I think the world is even more cruel to fat women, by the way. I also think there's maybe a bit more of a support system, or at least permission to talk about it amongst themselves in a way that there hadn't been for men. The first time I felt any sort of approval for my big fat body, I played football all through grade school, middle school, high school. That was the first time I ever got any information that was positive about my body, so that was the first role I played. I played defensive tackle on the football team, and it was good that my body was big, as long as I used it to hurt other kids.

I'm not trying to paint some sob story. I loved it. I loved the sound of the drums. I loved wearing the jacket. I loved getting to be part of this team, the togetherness, the camaraderie. It was fantastic.

Kousha Navidar: You yourself had described yourself in the book as being popular, too, in high school, right?

Ian Carmel: I was a popular kid. Yes, absolutely. I got to go to parties. I had lots of friends. That popularity definitely had a ceiling that I saw other popular kids not hit. Part of that was self-imposed by myself, the way I saw fat people's romantic lives portrayed in popular media, which was nonexistent or as a laughing stock, right. If, in fact, I tried to kiss a girl, the girl, people laughed. That's what I saw. That was the ceiling that was posed on my popularity in high school, and I loved it, but at the same time, there was this awareness that I was only popular as long as I decided to use my body to hurt other kids, right.

Once I got out of high school, once that football thing got taken away, I quickly found comedy, and I made fun of myself. That's the first thing you do is like a stand up comedian, right? You walk up on stage, and you're like, "I know what you're thinking. Da da da da da da da." My first joke, I would go up on stage and say, "My name is Ian Carmel, which is ridiculous because I'm a six-foot, 300-350 pound Jew, and my name sounds like a whimsical British candy store, right?" I don't know if I can say. "My name should be Shlomo Pudding Boobs," basically.

Kousha Navidar: Yeah. Boobs is okay to say

Ian Carmel: Boobs is okay, yes, right.

[laughter]

Kousha Navidar: [unintelligible 00:07:31]

Ian Carmel: That wasn't the word. I replaced the more I think, acceptable word. My catchphrase should be, "Better put some butter on it."

Kousha Navidar: Right.

Ian Carmel: In my head, I'm like, okay, skewering the image of the fat comedian a little bit, but really, I was making fun of myself. I found a new role that I could play as long as I mind my own pain for it. Again, I'm making this sound like it was some miserable experience. I loved high school, which I think is pretty rare, especially for someone on public radio.

Kousha Navidar: [laughs]

Ian Carmel: [laughs]

Kousha Navidar: I also loved high school-

Ian Carmel: Okay, fantastic.

Kousha Navidar: Between the two of us, maybe we can be the outliers on the right-hand side of that.

Ian Carmel: I think we represent 100%. I don't know how Ira Glass's experience was, but I bet it wasn't great.

Kousha Navidar: Well, Ira Glass, if you want to call in 212-243-WNYC, but go ahead.

Ian Carmel: Hit us up. Let us know if you had fun in high school.

Kousha Navidar: [laughs]

Ian Carmel: We'll be listening. Then, I really enjoyed my experience in stand-up comedy, but the entire time, it was me taking these feelings and these and this pain and these fears. Definitely a lot of fear and anxiety about being fat and my experiences and stuffing them away and never wanting to subject anyone else to them. That was as much, I think, imposed by society a little bit, but there's this insidious thing about bullying, which is, I think it's like the opposite of termites, right? They say once you see one termite, it's too late. They're in the foundation. Once you get bullied, once you assume the same thing, even if it's not, but you assume there's whisper filter.

Kousha Navidar: Whisper came through which you see everything in the world.

Ian Carmel: Right, everyone's talking about how fat I am, how disgusting.

Kousha Navidar: Do you feel like most of your bullying came from yourself, or did it come from others?

Ian Carmel: Definitely for myself, looking back on it, and there was a fair amount coming from other people. Even just like the passive bullying of just being fat in a world that is --sorry, not to take the talk thing from my book- but, like, being fat in a world that is built for thin people, right. I went to Six Flags with my family when I was probably 12, 13 years old and waited in line for a roller coaster for two hours in the hot sun. It got up to the front of it, and they pulled the bar down, and the bar didn't fit over my belly, and that sucked because you just waited two hours, and it's humiliating. Then you get up and, like, so that's the passive bullying of the world. Then somebody in line yelled out, "Get in my belly," from-

Koudra Navidar: Austin Powers.

Ian Carmel: Austin Powers. That's more of the act of bullying, so you're getting all those at the same time. You go into clothing stores, and the person working there is like, [sniffs] "I could check the back." Where it's like, well, if you have the size, put it out with everybody else. I shouldn't have to go through this perilous journey just to see if you have enough fabric to cover my disgusting torso. Like, put it out with everybody else. Even now that I've lost quite a bit of weight, but I still wear, like, XL or XXLs sometimes. Even still, I get the, "We can look in the back." It's humiliating.

Kousha Navidar: It's feeling like you are relegated to the back.

Ian Carmel: Absolutely. Like there's something. I. Especially right now where, Americans, we're fat. A lot of us are fat. I say fat, by the way. I don't think there's anything wrong with the word fat. I think if we want to change the way the word fat feels, we should change the way we treat fat people, and that'd be a great way to fix it.

Kousha Navidar: Ian, we got a couple calls. I want to take them before we go to break.

Ian Carmel: Sure.

Kousha Navidar: Here is Cheryl in Lindenhurst, Long Island. Hey, Cheryl, welcome to the show.

Cheryl: Yes, thank you for putting me on. I want to thank you so much for writing this book because so much of it is resonating with me, and it's actually bringing tears to my eyes. I grew up in a family where my weight was always an issue. I was always fat. I was chubby, and I just grew up thinking, "Well, that's my lot in life." I realized now that I was really beaten down about it. Then I went into a relationship with a boyfriend who would tell me, "Well, if you lose 50 pounds, I'll marry you," and I found that acceptable because of the way I grew up.

My weight went up and down, it fluctuated. Then about five years ago, six years ago, my weight reached almost 300 pounds. I'd go to bed at night, and I'd pray to God, "Please don't let me wake up." That's when I knew I had to do something, so I took myself off to Weight Watchers. I lost 108 pounds. I felt great about myself. The pandemic hit. I put on probably about 30, and I started all those old feelings of being fat, of being called a fat pig and being bullied about my weight started to come back. I worked really hard to say these feelings are not acceptable, and so I'm back on my Weight Watcher journey again and slowly taking off those 30 pounds.

Kousha Navidar: Cheryl, I want to thank you so much for calling and for sharing that. We're thinking of you and we so appreciate you sharing that difficult, but it sounds like an empowering journey that you're going on right now. We are sending you the best, and thank you so much again. Folks, we're here with Ian Carmel, who is the author and comedian. The book, his memoir T-shirt Swim Club: Stories From Being Fat In a World of Thin People. We've got Catherine in North Bergen, New Jersey. Hey, Catherine, welcome. Welcome to the show.

Catherine: Thank you so much. What a fun topic. Yes, I've been a big person my whole life. I knew it when I was three years old. Hugely athletic family, seven brothers and sisters. All I ever really wanted to be was an actor, so just very quickly. As I went to first grade, my mother looked at me and the box-pleated Catholic school skirt, and she said, "Oh, boy. That makes you look twice the size. Too bad. You have to wear it for eight years," so that was first grade. Now let's fast forward because I know you want to talk about high school, so it's about to go to high school on the first day, and she looks at me, she says, "Catherine, you're never going to have beautiful clothes. You're never going to have a man, and no one's ever going to give you a good part." Okay, that was how we started high school.

Now, let's fast-forward to videotape. I became an opera singer. I sang in 28 countries. When I first went to New York as an actor at 17, with $60, I became a couture seamstress. I had all the beautiful clothes I could ever want. I married an Arabian prince, and often in my life, I've looked back at those things and thought, "Wrong again, Ma."

Kousha Navidar: Catherine, I'm going to pause you there. Thank you so much for going through that. Ian, I am sure you can relate to a lot of that questioning about the direction you wanted to go and what was possible. I mean, there's a text here that says, "As a fat person, I always say, every fat person wakes up and says, 'Today is the day I won't overeat.'" I'm just wondering, listening to Catherine, hearing texts like that, does that resonate with you, with your own journey?

Ian Carmel: Everyone we've spoken to so far has resonated with me in big, meaningful ways. From the humiliation as it coming from the calls coming from inside the house, as it were, as a kid, to that defiance. To feeling that like existing in defiance of everything that you were told you couldn't be, and I think that's wonderful. I think adults don't really know how to talk to their kids about being fat unless it's because you see how much pain the world inflicts on fat people, as a parent, I'm sure. I don't have a kid myself, but my sister, who I wrote the book with, does. I've talked to my parents about it. You want to do anything to get in the way of that pain.

Sometimes the only thing you can think of is saying, "Unless you get smaller, the world is going to hurt you. The only way I know of trying to motivate you to get smaller is to tell you that, or to shame you or to scare you." Unfortunately, that causes stress. and if we're fat in the first place, we usually don't respond to stress with it's fight or flight. Oftentimes, we go flight and we fly into our comforts, which is food, which is eating, which is hiding from things. People are so condescending to fat people. Every morning, we do wake up and say, "Today is the day I'm not going to overeat," right. Nobody knows how to lose weight better than a fat person.

People, you know what? It'll come from doctors, it'll come from people in your life. It'll come from Bill Maher, who is saying, "Hey, fatty, just put down the cookie and pick up a kale chip." We know that. We understand that better than anyone. We know that intimately. Every fat person has been on a million diets, and we've all had them fail because most diets aren't compatible with living a real life. It's all these efforts to shame us and scare us when I think the best thing you can do, especially if you're a parent, is have a conversation with your kid, if you have a fat kid, that is either positive or neutral about their body.

You don't have to be positive about fat in its relation to your health or anything like that. You can have honest conversations about that, but I think oftentimes people are afraid to talk about it at home because they want the house to be a safe haven. That's what my house was like growing up. I felt fat everywhere but at home, but that meant I wasn't having any conversations about my body that were either positive or neutral. I was only having the negative ones outside of my house.

Kousha Navidar: Well, we have a caller who is a parent that would like to chime in. Here's Bill from Brooklyn. Hey, Bill, welcome to the show.

Bill: Thank you. I have a child in elementary school, and he's always been on the upper end of the percentiles for his weight and body mass. Watching the way the world is starting to react to him is just heartbreaking. I keep thinking that this is just such a relentless form of prejudice. If you substituted any other kind of identifying term or identity for fat, you'd never be able to say those things out loud.

Kousha Navidar: Bill, what are some ways that you're trying to support your child? Hey, Bill, you with us?

Bill: Yes. Telling him that he is perfect just as he is, and making sure that he eats healthily and stays active.

Kousha Navidar: Bill, thank you so much for calling and for sharing that. Ian, as you're listening, that resonates a lot with some of the things that you were saying before, right?

Ian Carmel: Yes, absolutely. I think that positive feedback is good. I think having frank conversations with your kid about how they're feeling and any bullying they might experience is a positive thing you can do. I think just encouraging your kid to have an active relationship with their health is a very important thing to do, because just speaking personally, I didn't. You can be fat and you can be healthy.

There are a lot of people who we would consider fat or who would be considered obese on the BMI scale, who have very active relationships with their health. I think it's important to let fat kids know that and to remind them that. Go to the doctor with them, make sure that that doctor isn't leading with, "You're fat, and that's a problem." Go into the doctor and make sure that they're leading with, "Let's talk about your health. Let's look at other metrics that aren't the number on the scale, that aren't BMI. Let's talk about is your blood sugar high?' Okay. You can address that in a way that isn't necessarily fat shaming. Your blood pressure, those kind of things.

Kousha Navidar: Your point about it being the filter through which you see the world and it being a world that's dictated by thin people, I think is also quite interesting. I mean, my producer just sent me a tweet that Emma Fitzsimmons from the New York Times, who's the New York Times bureau chief in city hall, just put out that said Mayor Eric Adams just told a reporter at his weekly news conference that it looks like he's been working out and working on his summer body. That's just like everything that we see is through-- yes, go ahead.

Ian Carmel: It is. You don't want to be a bummer, right? You don't want to be the person who say, like, "Hey, if you've been working on your arms, if you've been hitting curls at the gym and you want to come in, your biceps popping out of a tight t-shirt, we should." Maybe the mayor shouldn't be commenting on anyone's body, is probably the right answer.

Kousha Navidar: Right.

Ian Carmel: You don't want to not be able to do that at a barbecue or anything like that. I personally don't think we should chuck the baby out with the bath water. I'm not one of those people. I just happen to believe that we don't need everything to be quite so buttoned down, but a fat person works out, too, right?

Kousha Navidar: Right. For more than eight years, you were a writer on The Late, Late Show with James Corden. Some of the jokes that you wrote were self deprecating jokes about fat people, which you knew would work. Do you feel like fat jokes are looked at as critically as other kinds of jokes in terms of crossing a line or what was your experience looking back on those jokes?

Ian Carmel: No, certainly not. Certainly not when it's a fat person delivering them, which is what we were doing. James is fat. I'm fat. I was fatter then. I would write these jokes that I knew would work for him because I knew they worked for me when I did stand up. They operate on the same principle. No, that line is barely there for other comedians.

Kousha Navidar: We just got a text that says, "What, if any, discussions did Ian have with James Corden about struggling with weight?" Like, how did that all play in with the way you decided to tackle it?

Ian Carmel: At first, it didn't. The first, like, three, four years of the show, you are figuring out as you go. You're building the boat after you've launched it out to the sea, right? We were doing anything. We telling fat jokes, making, his weight the butt of jokes in sketches. I remember an early sketch where we had him and David Beckham both shirtless, during this perfume commercial. It was the same thing that the Patrick Swayze-Chris Farley Chippendale sketch worked on, where it's like one classically handsome dude and then one guy who, of course, it's ridiculous that anyone would find him alluring in any way because he's fat and shirtless and we would do that.

It hit an inflection point for us when Bill Maher, who we shared a studio building. We were in TV City in West Hollywood, did this rant at the end of one of his shows, talking about how we should bring back fat shaming, as though it had ever gone anywhere in the first place. That we would needed a fat shame fat people for their own good, and we needed to do it because they were harming themselves and they were harming the economy, [laughs] and the healthcare industry, by taxing it too much. We were sitting in a meeting, and that clip had gone viral.

We were just like, "You're the perfect person to say something about this. You have a show. You have a platform. You're a fat person. You've been fat your whole life. You know better than anyone that fat shaming hasn't gone anywhere," because he experiences it and works in defiance of it throughout his entire career. Sometimes in defiance, sometimes in compliance with it, to be frank. We sat down and the two of us wrote something together. I think the thing that we did on The Late, Late Show that I'm the most proud of, that and the Paul McCartney Carpool, I think won it, too. Where he said, "You know what? You don't need to fat shame us. We live in constant shame. That doesn't work. We need to be supported. We need to be helped. We need to be shown humanity. "

After that, we stopped making fat jokes in the monologue. We were like, "We can't be saying this out of one side of our mouth and then out of the other, participating in the system that has devalued us for our entire lives."

Kousha Navidar: If you could go back, would you have done anything differently back when you were making those fat jokes?

Ian Carmel: I think for the first few years, yes. I would have loved if we could have gotten there sooner because he's a funny guy. We didn't need to do that. We didn't need to throw ourselves overboard for the sake of a laugh/ Every now and then, it's fine. You can do that. Again, I don't want to live in a world where there's no fat jokes. I want to live in a world where life is better for fat people in general. and then we can keep some of the jokes. That's fine. Just let me buy a shirt. Let me go to the doctor and actually discuss my broken ankle instead of him bringing up my blood pressure first.

Kousha Navidar: It sounds like you're almost relying on it, which is interesting because it reflects something you said before the break, which was you just keep going back to what you felt safe in, where the comedy felt safe. That seems like an interesting reflection there.

Ian Carmel: Oh, absolutely. Fat jokes do feel safe because you've been making them since the first moment you found out you were fat at recess, when some kid tells you you're fat, and so you find out that fat's a thing. That you are it, and that it is bad all at the same time, a real triple crown, baby.

[laughter]

Kousha Navidar: I think we got time for just one more quick caller. Let's take Charlotte in Carmel, New York. No relation with our guest. Charlotte, hey, welcome to the show.

Charlotte: I'm delighted. Thank you for writing this book, and I'm going to go out and buy it. I stopped listening to Bill Maher after that rant. That was the end of it for me. One of my pet peeves, I've been everything from a medium to a XXXL. Where they put the clothes for when I'm at the larger end, they either stick us at the front so everybody knows where the fat girls are, or they put us in the farthest corner with no room between the racks. Why we can't shop with everybody else? Why we can't get clothes that look like everybody else's, not just great big squares with four holes in them, I don't know, but I'll take the comments off air. I love this segment. Thank you.

Kousha Navidar: Charlotte, thank you so much for calling and for that shout-out. We really appreciate you sharing. Got about 30 seconds left, so in that time, people that take this book that they read it, what do you hope that they take from it?

Ian Carmel: I hope they take a conversation about fat that is not necessarily negative. One that is full of joy and empathy and also for my little sis, someone who has a doctorate in psychology and works in nutrition. Also information. In each one of these chapters, I plumb my soul and try to bear everything that I was going through. Then she comes through and takes that information and tries to be like, "And here's what you can talk to your kids about, or here's what adults are going through when that happens." It's the hope that people know that they're not alone and I know maybe that sounds trite, but it really is like, you're not alone. There are other people going through this, and you don't have to go through it without help.

Alison Stewart: That was Kousha Navidar's conversation with Emmy-nominated comedian, writer, and actor Ian Carmel. His memoir is titled T-shirt Swim Club" Stories from Being Fat in a World Full of Thin People.

[00:26:22] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.