This year, we've been spending time at M.S. 22 in the Bronx. It's one of Mayor Bill de Blasio's Renewal schools, the 94 low-performing schools that are getting more attention now with extra services and professional development. We've reported on their optimism in the fall and the challenges of changing the school culture.

Located in Morrisania, with about 430 pupils, M.S. 22 faces a deadline of this June to turn around stubbornly low test scores. In 2015, just under 5 percent of its students were proficient on the state's English Language Arts tests, and only about 3 percent were proficient in math. If it doesn't, it will have to close or come under state receivership.

Principal Edgar Lin said recently he knew several of the reasons his students struggled with reading: many are new to English and grew up in low-income households where they were less likely to be exposed to as many words and books as children from wealthier families. But while he describes "amazing progress" this year among the lowest-performing students, he said it's still not enough. More than 90 percent of all students were still reading below grade level when the school gave assessments in December and January.

The assessments pinpointed a weakness: limited vocabularies. This is why it's so hard for them to read books like "Pygmalion," or a poem by Langston Hughes or grasp the history of the Revolutionary War, all standard topics for middle schoolers.

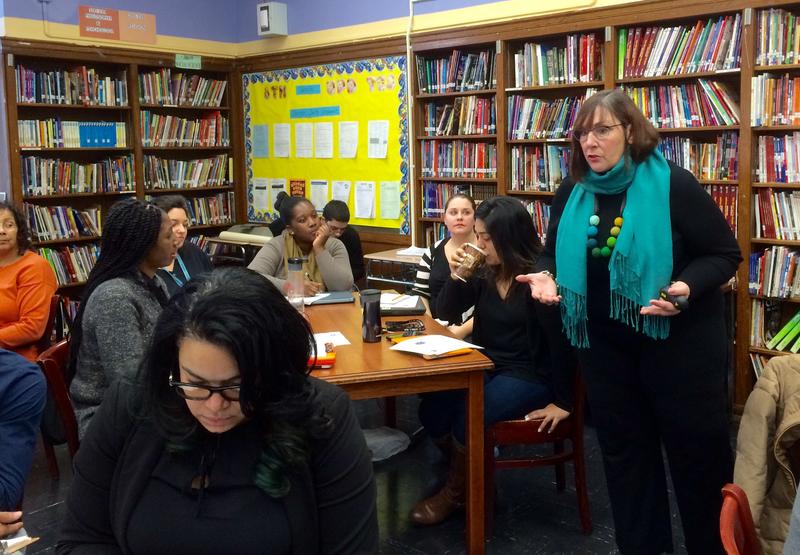

To boost students' vocabulary, the whole staff at M.S. 22 - except the two physical education teachers - attended full-day workshops in January with Kimberly Tyson, a former teacher and literacy expert with Solution Tree in Indiana. Here are some of her tips:

The greatest indicator of reading comprehension is vocabulary. "Kids who read more, or who are read to or read independently also have broad vocabulary," said Tyson. Those students also tend to enjoy reading. But when students don't have a broad vocabulary, they are less likely to read on their own and things only get worse as they get older. Academic language increases in middle school, with words like "objective," "subjective," "predict," "compare and contrast," and "justify." If students are missing these mid-level words, or don't understand them in context (especially on test questions), they are going to fall behind. This is why students are encouraged to read for pleasure.

Most teachers don't pay enough attention to vocabulary. "The biggest mistake teachers make, that we know, is actually very little vocabulary instruction goes on," said Tyson.

When a student doesn't know the meaning of a word, she said the most common reaction is for the teacher to explain it or give a synonym. They might also put lists of relevant words on their classroom walls. There's nothing wrong with that, she added, "it's just not enough."

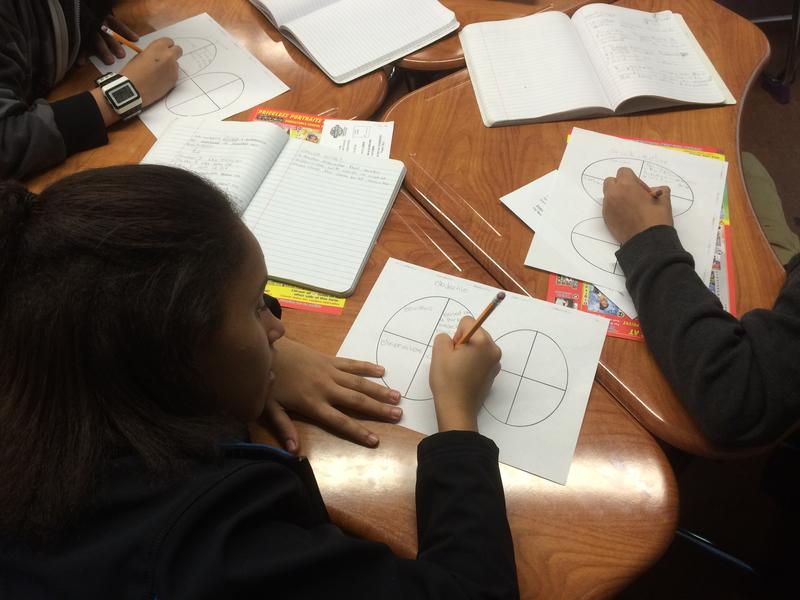

She encourages teachers to use visuals, some good online dictionaries and to have their students act out a word or come up with a definition in their own language. For example, teachers can provide "concept circles," divided into quarters, for students to write down four different definitions of a word.

Students don't learn a word right away. Tyson said studies show they need at least six exposures to a word in order for it to really sink in. This is why they should not be told to use the word in a sentence as soon as they learn its meaning. They need to spend more time understanding and visualizing the concept before they can use the word.

Tyson also has a list of 10 do's and don'ts for teaching vocabulary.