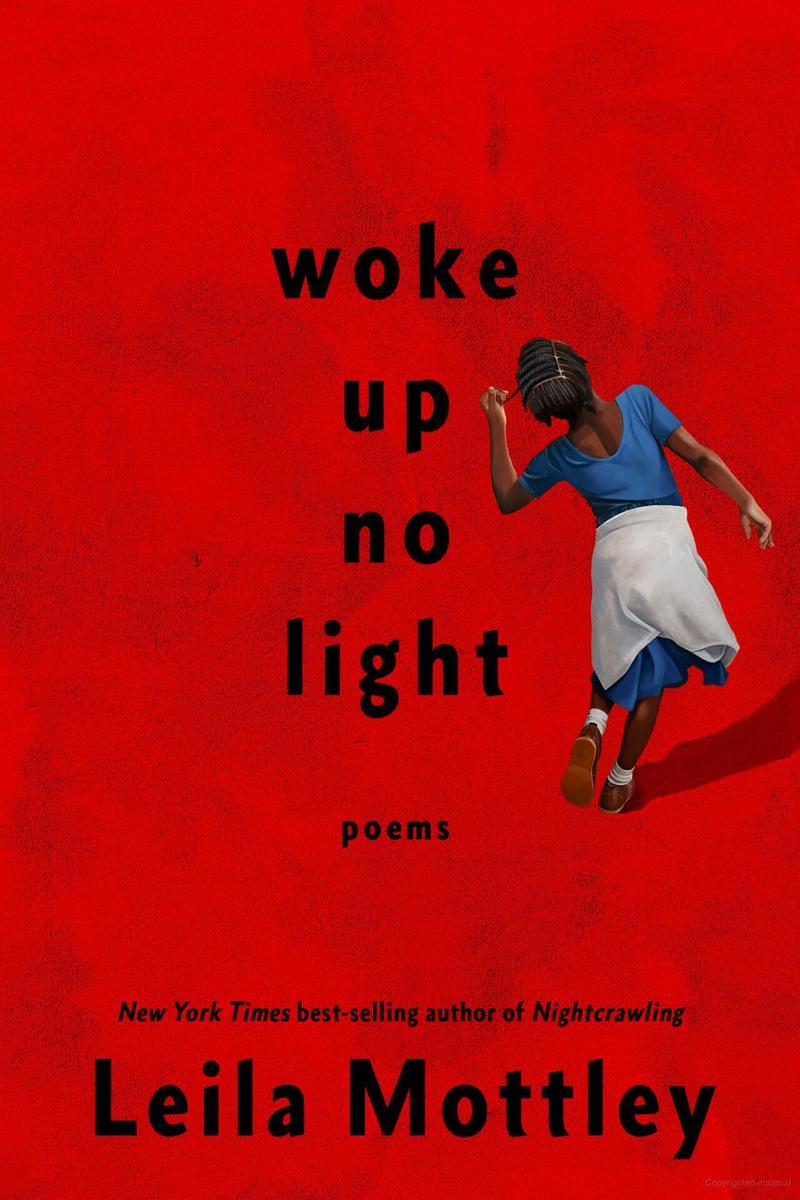

Leila Mottley's Debut Poetry Collection

( Courtesy of Knopf Publishing Group )

Celebrated young writer Leila Mottley has followed up her debut novel with her debut poetry collection. She joins us to discuss Woke Up No Light, and read some poems in honor of National Poetry Month.

This segment is guest-hosted by Kousha Navidar

[music]

Kousha Navidar: This is All Of It. I'm Kousha Navidar, in for Alison Stewart. We're wrapping up today's show with a little poetry in honor of National Poetry Month. Let's talk about a debut poetry collection from 21-year-old New York Times bestselling author and former youth poet laureate from Oakland, California, Leila Mottley. Her new book is full of hymns and rhythmic pieces that reckon with themes like reparation, restitution, and desire. The poetry collection is a follow-up to her highly acclaimed third novel Night Crawling, which follows a young sex worker in Oakland who's embroiled in a police scandal.

She started writing the novel a month before she turned 17, and later, it became Oprah's book club pick and long-listed for the 2022 Booker Prize. That made her the youngest person ever nominated for the award, which is super cool. Leila's new poetry collection is titled Woke Up No Light and it's out now. Quick plug. Tomorrow night at 7:00 PM, Leila's going to be at Poetry Night along with the writer Tatiana Johnson-Boria at Books Are Magic on Montague Street in Brooklyn. Right now, Leila is here with us to talk about her new collections and maybe share some poems if we're lucky. Leila, hi. Welcome to All Of It.

Leila Mottley: Hi. Thanks for having me.

Kousha Navidar: Absolutely. Would you start us off by reading the poem, How to Love a Woman Sailing the Sky?

Leila Mottley: Yes.

How to Love a Woman Sailing the Sky

The only thing that surprised me more than all the oceans soaked in salt was the day after all my chasing, all your running

You stopped twirled around and touched your fingertips to the crescent of my collarbone

I have been a woman sailing the sky

I have been a girl clung tight to the branches

I have been a daughter splayed out on a boat of ice and then I was yours

I was born to floating people who drank from the clouds that held them until there was nothing but blue and one spectacular drop

I searched for something solid so long I forgot my body itself was not made of mist or malice

You reached out your hand

I flinched until you showed me you were not reaching through me but for me and then I was yours.

Kousha Navidar: So much about that poem and maybe this whole collection feels like it echoes themes of change and of desire. Does that resonate with you, that characterization?

Leila Mottley: Absolutely. I think this collection was a way for me to capture my entire journey through childhood and into adulthood and show all of the change and turmoil that comes with growing up.

Kousha Navidar: Were these poems that you had developed over that period, or are these more retrospective that you're writing recently?

Leila Mottley: Both. There are a couple that were from when I was 15 or 16, and then there are a lot of them that are over the past few years of my life as I've reflected back and grown into this new version of myself and looking at how do we live in a world and grow into a world that is often feels like it's on the brink of destruction.

Kousha Navidar: This one that we just heard, How To Love a Woman Sailing The Sky, do you remember when you started that, how old you were?

Leila Mottley: Yes, that's one of the last poems that entered the collection as I was thinking about what does it mean to trust and to wholly enter love and life when you've come from a past of distrust.

Kousha Navidar: When you come from a path, a past of distrust is such a heavy term. I think about how your writing must change over time. This one you wrote recently, there's some you said from when you were 15. Can you see differences in your writing style? How would you describe it?

Leila Mottley: Absolutely. When you're a teenager, everything's heightened. I think a lot of the poetry then was very highly emotional and intense and tended to be longer and more spoken word based. Then some of my poetry now, it tends to be a little bit slower and more contemplative.

Kousha Navidar: How does slow and fast show up in the writing? Is that the rhythm of how you would choose to?

Leila Mottley: Yes, absolutely. I write by hand mostly when I am writing poetry, but I think that when I was younger, it was a lot of scribbling, and now, I'll take my time with it. I feel like I have more time to really soak in and sink into the work and think about it in its dualities.

Kousha Navidar: Oh, interesting. Listeners, if you're just joining us, we're lucky to have Leila Mottley here with us in studio. Her debut poetry collection Woke UP No Light is out right now. I'm thinking about before this book, you were a New York Times bestselling author. You served as the 2018 Oakland Youth Poet laureate. What sparked your interest in poetry, and when did you decide, "Hey, since I'm 15, I've got these poems, I want to put them into a collection"?

Leila Mottley: [chuckles] I've been writing poetry and fiction for as long as I can remember. I started writing poetry when I was six, and then I started writing novels when I was 14. The two have always coincided for me but taken their own separate lanes, and I wanted to be able to do both at once for the first time in my life. I think that they have such influence on each other on-- my fiction shows up in my poetry at times, and my poetry definitely shows up in the way that I write prose. Being able to have them both exist at the same time, I think, allows me more freedom in my work.

Kousha Navidar: Oh, wonderful. Listeners, I just want to put out something. I made a mistake in the way that I pronounced Montague Street in Brooklyn, I'm sorry about that. Just to make sure everyone is aware for the quick plug, tomorrow night at 7:00 PM, Leila's going to be at the Poetry Night with writer Tatiana Johnson-Boria at Books Are Magic on Montague Street. My bad. It's in Brooklyn. Be sure that you check it out. I'm thinking about the similarities between this collection of poems and your most recent novel, Night Crawler. You mentioned that your prose influences your poetry in both ways around. Can you dive into that a little bit? What do you mean?

Leila Mottley: I think in the tradition of a lot of Black women writers, I think language needs to be able to move boundlessly. In the way that I write fiction, I infuse it with poetry and thinking about how we rarely get to see Black women, Black girls' interior lives as the poetic things that they can be and are. I think it's integral to the way that I write fiction that poetry be a method of being able to process a world that is so hard to live in tangibly and viscerally and the ways that we cope through language.

Kousha Navidar: It reminds me of this interview you did for the San Francisco Chronicle. You mentioned returning to poetry after publishing Night Crawler and you said that, "Poetry itself is more insular," which I thought, can you talk to me more about insularity and maybe what does poetry offer you as a form of expression?

Leila Mottley: I think a lot of us grow up writing poetry as a journalistic way of expressing ourselves and understanding ourselves, and I definitely did. I think that there's something about poetry that is kinetic and it's vibrational and we feel it. I think especially in age where we have shorter attention spans in a TikTok world, I think that, a lot of the times, we need to be able to consume something and understand it and feel it emotionally in a short period of time. Poetry allows us to do that, and it doesn't reduce its complexity either.

Kousha Navidar: I think that you have another poem for us, My Greatest Grandmother's Will. Would you be able to share that one with us?

Leila Mottley: Yes. This is an erasure poem.

In the name of state, of body, memory, and knowing

Now being one on the watery river of 300 Negroes called Nan, horses, and cattle, and life

I give my youngest boy one will and the Negroes shall descend

The lawful heirs of my body not to be sold away

One plantation, 100 acres bounding myself, my daughter

One Negro woman called, one Negro girl called, I rose with wine

It is my will that one child die

That so losing shall entitle one of my children to forever

I give unto my beloved girl this last day of 1,790.

Kousha Navidar: You mentioned that this was an erasure poem. It's from The Last Will And Testament of Nan: Pains in Slavery. Can you talk a little bit, what is an erasure poem?

Leila Mottley: An erasure poem is where you take a preexisting text and you essentially use a sharpie and you block out words and you create a new text out of it. This one in particular, I traced my genealogy back to one of my oldest ancestors and then found her enslaver. The thing about ancestral records is that the archive doesn't allow a lot of space for really any information about Black people, Black enslaved people, and so I went to the enslaver's records and found my ancestor's name in it and took that will and created this poem to give her an ability to speak from the past.

Kousha Navidar: Is this written from this perspective of her or from you? Talk to me about that.

Leila Mottley: Yes. I think poetry, it has layers. This one, I wanted to be able to add to the archive, and I think a lot of the times, what the archive lacks is humanity and story. This one, I wanted to give my great-grandmother the ability to speak through time.

Kousha Navidar: Yes, and through form too, I think, which is really interesting because a lot of the most striking poems were the ones that played with form. Listeners, you'll see this when you open the book, this poem, the words are spread out and scattered on the page. I'm also thinking of the poem Wet Nurse, which is earlier on here, in which you have two columns of short stand is down the page. I don't know if I was reading this right, but I felt like I could read the poem either up or down or side to side. It is, for me, such an interesting way of playing with language, but I don't mean playing as a juvenile thing, I mean it as looking through form as well. Can you tell me for this one with the word splayed across the page, how does that form affect the writing for you? What were you trying to do here?

Leila Mottley: It changes everything because you're working from a text that exists and recreating it. I think the archive demands us to be creative with it, to create history and knowledge where it doesn't exist and where there are these major gaps. In a lot of the more historical poems, the poems that are meant to fill those gaps, I looked at how I could use form in an inventive way to really think about the way that we see and the way that we look at things and what it means to be visible and what it means to be invisible.

Kousha Navidar: For this one, why go with this particular format? What was it about having the word so disparate from each other? Almost, it seems.

Leila Mottley: I think we need to be able to see the invisible space in order to understand what it means to occupy it.

Kousha Navidar: Listeners, if you're just joining us, we're talking to Leila Mottley, her debut poetry collection, Woke Up No Light, is out right now. I'd love to talk a little bit about the writing process for you. How did you learn to write poetry?

Leila Mottley: I sat down with a pen around when I first learned to write. I think I found words and language incredibly fascinating from a young age, and I've always been a reader. I think poetry came out naturally almost. Then I started reading a lot of poetry, and over my life, I've always been drawn to poetry as a form that can span so much. It's unpredictable, and that's the point of it.

Kousha Navidar: What's unpredictable about it?

Leila Mottley: Poetry, particularly contemporary poetry, is partially born out of the tradition of jazz and what it means to improvise and what it means to deal with rhythm and with sound and with words in a way that we don't typically see them to break convention is the entire point. I think that that allows us to have fun and to play and also to find things where I think they're often lacking and missing.

Kousha Navidar: Do you use other art forms to inform it because you mentioned it's like jazz? Do you listen to jazz, or are there other elements?

Leila Mottley: I do, I do listen to jazz. Yes, I grew up listening to jazz. My dad is really into jazz, so I definitely think that that has had an influence on my poetry. I also grew up reading a lot of Ntozake Shange and Sonia Sanchez, who are both poets that use language and just take new words, create new words. I think that reading that when I was young allowed me to understand that there are no limits to poetry. I think the minute that you learn that you don't need to be confined in this art form, you get to really do whatever you want with it.

Kousha Navidar: I want to nerd out with you for a second here because I hear that, and as somebody who plays jazz, I think, yes, that's absolutely true. Simultaneously, when you learn how to improvise, for instance, first, you have to learn chords, and I feel pros might be that, but you're the expert here. What are the fundamentals? What are the carrots and the broccoli that you have to do as a poet to really be able to break form?

Leila Mottley: Well, I think you have to know the convention to break it. I think understanding the way that form has been used in the past, understanding the origins of different forms, understanding why you break it and what it does to subvert a standard, and especially when you're talking about free verse poetry, there are no rules, and we're also trying to conjure feeling. To do that, you have to understand what it means to soak it up, what it means to be the audience, and to be the listener and to be the reader, and to have a feeling brought up in you, and to understand why language does that and how language does that.

Kousha Navidar: I would love here to listen to one more poem if you've got it, and maybe apply that and see how it works out. I think you've got one more, On Starting Over.

Leila Mottley: Yes.

On Starting Over

I rent an apartment where I can smell the lake

For a reminder of all the past lives that have sunk to the bottom of this city

I open my windows just to air out the shadows of this place

Cozy up on my mattress straight from the box and don't even feel the pee beneath the bed

On the first morning of the first day of my new life

A seagull flies through my window and stains my carpet in bleach-white feces

The seagull knows the color of the walls before I paint them

Knows the color of the inside of my stomach from the shine of my window glass

And remorse is a humid tornado

Consuming

I'm not saying I couldn't have closed the window

I'm saying I did not and now there is a flock inside the bedroom I thought would be the first thing I called my own

After all those years spent packed body-to-body

Yearning for an exit

A new beginning is only as shiny as the window shattered just to walk through

You will always find glass in the cracks of your floorboards

Your bloodstream

I freedom fury

I whine and war and wrestle

I fold and cut an orange picked from a tree I pretend is mine

Reinvent yourself enough times and you won't know whose hands wrap around your throat

I rent an apartment and think it can erase me

I rent a new rib cage and think it can protect me from everything that has already ruptured

When you find seeds inside your orange slice, you spit them out

Not because they cannot be eaten but because you are craving sweet and they are bitter

You have plans to fly across the city and there is now a seagull by your side and what cannot kill may choke

A shattered rib

Broken glass

Regret is unholy, not unnatural

If I want my seeds back, I will cut another orange

You cannot reverse

You can only revise

Open the window

Let your past selves flock at your bedside

Let the citrus absorb and become you.

Kousha Navidar: I'm listening to it and I'm reading it now at the same time with my version of your collection. You talked earlier about rhythm and how things feel slower for you writing, but I read this and I see it and it's quite fast. It's very punctuated. Can you tell me about the inspiration in here, what you're trying to say in this piece?

Leila Mottley: Yes, I think that a lot of us in adulthood, we're trying to start fresh and we're trying to figure out how to invent ourselves but we can't escape our pasts either, we live with the remnants of who we've been. This poem was created in fragments, and I wrote it in these different fragments and then put them together in a way that I think ends up conjuring the feeling of starting over and then of being pulled backwards.

Kousha Navidar: Is there anything about this piec to go back to what we were talking about before with breaking form that you tried to do a challenge or an element that you wanted to challenge yourself with in it?

Leila Mottley: Yes. I think this poem takes different images and combines them despite them not necessarily going together. It had started with two separate poems, and then I started to think of what does it mean for worlds to collide. Then I created this poem out of it where we have both this idea of citrus and what it means to want something and then to regret something. Then this idea of these seagulls and glass and home and all of these things colliding together in one poem.

Kousha Navidar: That line really sticks out to me. I fold and cut an orange picked from a tree I pretend is mine. It sounds like change, sounds like discomfort. Is there a moment in your life that you felt like you're outside of your comfort zone that inspired this piece?

Leila Mottley: I think every time I move, if you've ever moved, it's a stressful process, and you almost feel like you don't know where you are that first night that you're in a new place. I think that's a lot of what growing up is, is being in this world and realizing there is no other home and the out-of-body experience that that is.

Kousha Navidar: It's funny that the last time that I moved is actually from your neck of the woods over here.

Leila Mottley: Oh, really?

Kousha Navidar: Yes, from the Bay Area back to New York City, which is wonderful. I'm sure a lot of listeners can commiserate with that challenge that you're talking about. Who are some of the poets that you have your eye on right now, folks that you admire, where you're getting inspiration from?

Leila Mottley: Mahogany L. Browne is an incredible poet. Danez Smith, their second, fourth collection, I don't know, they've done a million, is coming out this year. I'm thrilled for that. Ocean Vuong, Eve Ewing, there are so many incredible poets out there.

Kousha Navidar: You're looking to be at Poetry Night coming up, and I just want to plug it one more time. You're probably going to see a lot of folks when you're there that enjoy your pieces. How does it feel to be in community after you've written these pieces?

Leila Mottley: I think poetry especially is a communal art form. If you've ever gone to any poetry event, it's an experience. It's fun, especially during Poetry Month. You really get to sit in the space and feel everything in a way that you can't from the page itself. I think it's always special to get to be with people and feel the reaction in the moment.

Kousha Navidar: Well, listeners, listen, if you want to be able to share in that and be in community with Leila, tomorrow night at 7:00 PM, it's going to be Poetry Night, and she's going to be there along with writer Tatiana Johnson-Boria. It's going to be at Books Are Magic on Montague Street in Brooklyn. We've been talking to Leila Mottley. Her new poetry collection is out now. It's titled Woke Up No Light. She's been here, shared some stories, shared some poetry, Leila, thank you so much.

Leila Mottley: Thanks for having me.

Kousha Navidar: Absolutely.

[music]

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.