Lenin's Family History According to the Soviet Union

A Bedtime Story from Radio Moscow, might be the more apt title of this 1963 program, rather than "Lenin's Family." Never broadcast on WNYC (it was labeled "Prop" for Propaganda and relegated to the archives) this strange mix of radio drama and homespun instruction is a good sample of mid-century Soviet revisionist history. A schoolmarm-ish announcer spoonfeeds us the facts of Lenin's early life before actors voicing the roles of his father and mother take over.

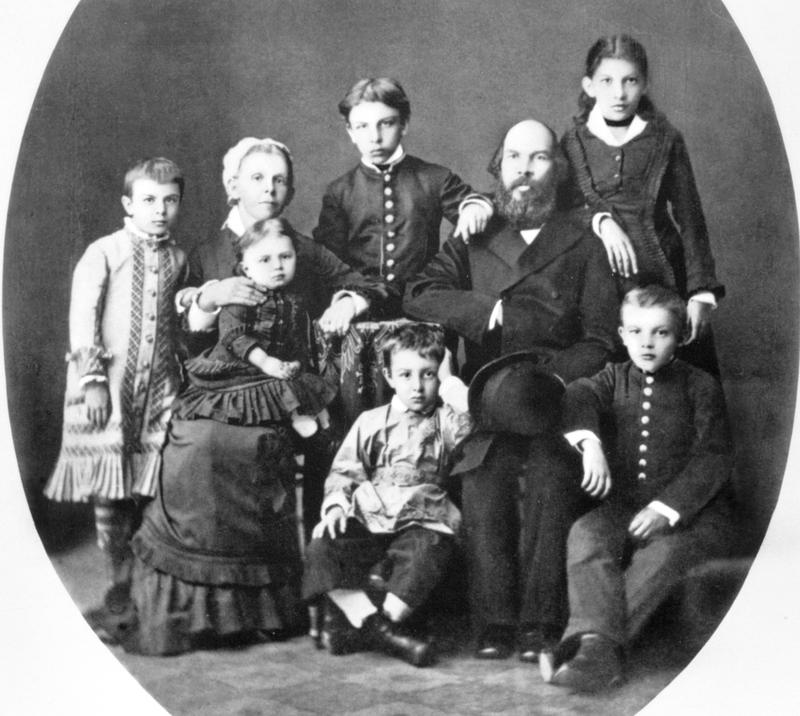

Little Vladimir "couldn't keep still for a moment." His mother, who played the piano, instilled in him a great love of folk melodies. (This, oddly, is accompanied in the background by a Beethoven sonata). The family's upper-middle class background (some historians even call them "minor nobility") is downplayed, with great emphasis placed on how hard his father, an inspector of schools, worked, and how his mother made sure he read no "trashy novels." The irony here is how stuffy and bourgeois the hagiography sounds, all while clumsy attempts are made to graft Marxist-Leninist principles onto an idealized Victorian background. Thus in the midst of this wholesome, hard-working family, it comes as a shock when Vladimir's older brother Alexander is arrested for "terrorism" and hanged. From this experience Vladimir (not yet "Lenin") learned, "the way of terror is senseless. We shall go another way." The story follows him as far as his exile to Siberia. The mother did not live to see, the announcer laments, "the most just order on earth established."

The story of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, aka Lenin, (1870-1924) needs no fairy-tale embellishments. What he accomplished is extraordinary enough. As always, what makes propaganda worth studying is where it diverges for the truth. Here, Lenin's upper middle class roots are obscured. As the Encyclopedia Britannica notes:

"It is difficult to identify any particular events in his childhood that might prefigure his turn onto the path of a professional revolutionary. Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov was born in Simbirsk, which was renamed Ulyanovsk in his honor. (He adopted the pseudonym Lenin in 1901 during his clandestine party work after exile in Siberia.) He was the third of six children born into a close-knit, happy family of highly educated and cultured parents. His mother was the daughter of a physician, while his father, though the son of a serf, became a schoolteacher and rose to the position of inspector of schools. Lenin, intellectually gifted, physically strong, and reared in a warm, loving home, early displayed a voracious passion for learning. He was graduated from high school ranking first in his class. He distinguished himself in Latin and Greek and seemed destined for the life of a classical scholar. When he was 16, nothing in Lenin indicated a future rebel, still less a professional revolutionary—except, perhaps, his turn to atheism."

A more glaring omission is Lenin's Jewish ancestry. One would think that by 1963 it would no longer be a taboo subject, however this "shameful" fact about Lenin, in a country where anti-Semitism still thrives, has never been fully admitted. As recently as 2011, the French newspaper Le Temps, in a story picked up by Time Magazine, reported that an historical exhibition:

"…adds a key new element to the official narrative. In a letter to Stalin in 1932 — six years after Lenin's death — Anna Ulyanova, Lenin's older sister, wrote that their maternal grandfather 'came from a poor Jewish family and was, according to his baptismal certificate, the son of Moses Blank.' Blank was born in Zhitomir, Ukraine. In her letter, Ulyanova said her brother 'had always thought highly of Jews.' She also urged Stalin to reveal Lenin's Jewish background, concluding that 'it would be wrong to hide it from the masses.' Stalin, however, ordered Ulyanova to keep Lenin's Jewish roots under wraps. A few years later, Stalin began to purge Jews from among the leaders of the revolution. Prior to his death in 1953, furthermore, he was preparing to send the whole Jewish population living in the Soviet Union to concentration camps in Siberia."

Radio Moscow, for many years the most public face of the Soviet Union abroad, is now mostly remembered for its later phase, when it produced such clumsy propaganda that only the most credulous listeners could take it for a serious news outlet. But at its inception the station was much more serious in intent and in the role it played. The magazine Rossiyskaya Gazeta, publishing in the Telegraph newspaper, reminds how:

"On October 29, 1929, Radio Moscow…became the first radio station in the world to broadcast to an international audience. It was followed three years later by the BBC, and then by Voice of America in 1942. By 1939, the station was broadcasting in English, French, German, Italian and Arabic and warning the world about the growth of fascism in Europe. Mussolini personally ordered Radio Moscow to be blocked, as did Hitler following the onset of the Second World War. The station would continue to inspire those involved in opposition movements throughout Nazi-occupied territories."