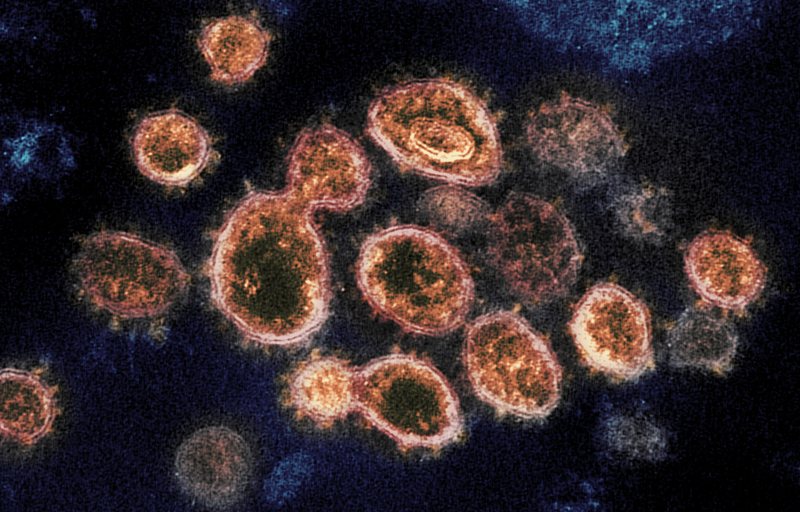

( Uncredited / AP Images )

Over a year into the pandemic, the origins of COVID-19 are still a mystery. Carl Zimmer, New York Times science columnist and author of Life's Edge: The Search for What It Means to Be Alive (Dutton March 9, 2021), talks about the different origin theories within the scientific community, and why the idea that the disease accidentally leaked from a lab in Wuhan, China has gained some credibility when it was previously largely dismissed.

[music]

Brian: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. It's still considered likely COVID-19 came from a bat, but it's actually becoming less clear how it got to us. A year ago, Donald Trump told reporters that he had reason to believe that COVID-19 started in a lab in China. You know that theory, a lab that had been studying coronaviruses in bats. Here's Trump talking to a reporter in may of 2020.

John Roberts: Have you seen anything at this point that gives you a high degree of confidence that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was the origin of this virus?

Donald Trump: Yes, I have. Yes, I have. I think that the World Health Organization should be ashamed of themselves because they're like the public relations agency for China,

Brian: President Trump a year ago with John Roberts from Fox. Following that exchange, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Trump's own appointee, in that very high position, contradicted the president in a rare public statement saying it agreed with the "wide scientific consensus that COVID was not man-made, but had evolved naturally from animals."

Fast-forward a year, the lab leak hypothesis has been picked up and dusted off from the bin mark conspiracy theory and put instead in the bin marked "unlikely, but definitely possible." Yesterday, in a written statement, President Biden asked his intelligence to redouble their efforts, to find the origins of the pandemic and to look into both scenarios that the virus evolved naturally, and that it was leaked from a lab. What changed, and why would this matter, if at all?

With me now is New York Times science reporter Carl Zimmer, he has been reporting on this, and he also has a new book out called Life's Edge: The Search for What It Means to Be Alive. Carl, great to have you back. Welcome back to WNYC.

Carl: Thank you for having me.

Brian: Can I clarify one thing right at the start that this isn't- nobody's saying this is a conspiracy, right? That if this was man-made, that it leaked from the lab on purpose as some Chinese plot of biological warfare against the United States or against the world, correct?

Carl: No scientists are saying that right now. Now, there were people in the Trump administration who were floating this idea that this virus was somehow created by Chinese government scientists or military scientists, intimating that this might be some sort of biological weapon that was unleashed on the world. When we're talking about a lab leak hypothesis, that's something totally different. That's the idea that scientists go out into the environment. They find some viruses, they bring them back into the lab, they're growing them to study them there. Then, someone isn't careful and they accidentally walk out with it on their shoe, or inhale it, or something like that.

It's an entirely different scenario than the real conspiracy theory stuff that we were hearing from some members of the Trump administration and was being promoted by the likes of Steve Bannon.

Brian: Right. Even if they do determine that this originated in a lab, it's still an unbelievably tragic accident, as far as all these experts are concerned that coronavirus got out into the world the way it did, either through handling bats in a food market or handling of experimental coronavirus in a lab, it's still an accident. There's consensus on at least that much?

Carl: We know that viruses do sometimes cause harm in live accidents. The last person to get sick from smallpox was actually someone who has got exposed to smallpox in a lab. In China, there was someone who was studying another coronavirus that caused SARS in 2004, she got sick and spread it to other people, including her mother who died.

We know these things do happen, but it's important to stress that there's no clear, concrete evidence that it actually happened in this case. It's just simply that a lot of scientists are saying now that there really just isn't a lot of information to make a judgment as to which explanation is more plausible. Was it a leak in a lab or was it something that happened often, some caves someplace, we just don't know because there just isn't enough evidence. What they're calling for is just, "Let's look into this more."

Brian: Listeners, do you have a question about the origins of COVID-19 for my guest, New York Times science writer Carl Zimmer? 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280, or tweet your question @BrianLehrer. Carl, people who give credence to the lab leak theory say the speed at which the virus spread was something to be suspicious of, that in a naturally occurring virus, it would take longer to mutate to become so spreadable. Can you explain that a little bit? There's a term Gain-of-Function research.

Carl: These claims make a lot of assumptions about what we do and don't know about how viruses work. I am very skeptical of them in general. As for Gain-of-Function, that is a very particular scientific kind of experiment. Scientists might say, for example, "Okay, here's a flu virus that infects birds, what would it take for it to be able to infect mammals?" They might do an experiment where they actually try to use the bird flu to infect mammal cells and mutations might arise. That might make them better at that.

There are other versions of this where scientists will actually splice in a piece of genetic material into a virus to see if it can gain a new function. That happened to the United States, I should say. It happens all over the world. It's a very common kind of study. There is some debate about, what level of safety scientists should use for these kinds of experiments, because you don't want to create a pathogen out of the blue.

This idea that somehow scientists were able to manufacture a coronavirus that could launch a pandemic, gives way too much credit to scientists. The fact is, and scientists themselves will tell you this, that we only started to understand a lot about how SARS-CoV-2 works and is able to spread so quickly after it became a pandemic, and scientists would look closely and say like, "Oh, this gene has something interesting that I hadn't really noticed before. Oh, that actually helps it to bind more tightly to sales. Interesting, that's something new."

You can't take that information into a time machine back and then use that to create a vaccine, a virus from scratch, or do some Gain-of-Function experiment. There's been a lot of confusion about these different kinds of experiments and what they can and can't do.

Brian: I did see that this past week the Senate unanimously agreed to include two Republican provisions to a huge package of China legislation aimed at prohibiting sending American funding to the Wuhan Institute of Virology or to the China-based "Gain-of-Function research." What are the scientific research implications? If it does turn out that COVID did come from a lab, will it be harder to receive grant money or funding to study viruses in the future, if people are worried that another pandemic could be triggered and that this is a valid laboratory-based concern?

Carl: As I mentioned, there have been debates in the past about what are the limits of virus research, when does research get too risky. It's not specific to this particular virus, and this is an ongoing conversation that scientists and governments need to have. Back in 2009, there was research, back when we were all worried about pandemic flu, there was research going on in this area of, and some people were concerned like, "Might you accidentally create a human flu this way?" Then people will counter and say, "Look, this might be the only way we can get these clues to know in advance what we're up against."

Now, if we stop, if we somehow say like, "Oh, let's not study coronaviruses at all, let's not go find out that diversity of coronaviruses. They're still out there in the wild," a lot of scientists say, "That's a really foolish plan because there's just lots of bat coronaviruses that we are still finding." Actually, the scientists, under fire at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, are playing a central role, in public they're sharing the details of a lot of these coronaviruses that just came out with a pre-print just a few days ago with eight new ones that no one had seen before. One of these could become the next COVID-19.

Brian: Right, although another bit of new information that we have is that researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology were sick with coronavirus-like symptoms back in 2019. We still don't know whether they were sick with COVID, but this is something that was previously denied. Right?

Carl: I think the key issue is, did they have COVID? Let's not forget this was in the middle of a pretty bad flu season in Wuhan. It could be that they had the flu instead. Also, you have to look at all of this information with a careful eye and use what we know now about the disease to think about it. What we know now is that the majority of people who get infected with this virus either have very mild symptoms or have no symptoms at all.

It's not as if a virus could have suddenly knocked out three people and sent them to the hospital without infecting anybody else. In fact, you would actually expect, based on the hospitalization rates, you would expect there would have been hundreds of other people who were infected at the time. Where's the evidence of that? Again, we're venturing out into reports from intelligence agencies that haven't been verified, where we don't have enough information to make this determination, so to really say like, "Oh, this tips everything over in some direction," I think is the wrong conclusion to draw.

Brian: Mook in Washington D.C. is calling in with a possible piece of evidence about there being a lab leak. Mook, you're on WNYC. Hi.

Mook: Hi, Brian. Hi, Carl. I'm just wondering because I think that when viruses are in nature sometimes they get less virulent because they basically want to survive in the host and then humans and the virus tend to coexist and it becomes less virulent over time. With this one, it seems like the variants are getting more virulent over time, which could be some evidence that maybe it is based in a lab. Just any ideas about that? Thank you so much.

Brian: Thank you so much. Carl.

Carl: There are a lot of ideas that people may have about, how virulent does a virus have to be? Does evolution drive a virus to be more virulent or last, or something like that? The answer is, scientists understand it is really complicated. In different conditions evolution may favor something being nastier or something being milder. The fact is that we are dealing now with variants of this coronavirus that are totally new, that only came into existence probably, say, in September, being [unintelligible 00:13:05], which some studies at least suggest put more people in the hospital. We may have been watching it becoming more virulent in front of our eyes, not due to some human manipulation, but because of the laws of evolution.

Brian: All right. Did coronavirus originate in a market or in a lab? The Biden administration is now officially engaging on that question. As we leave it there with New York Times science reporter Carl Zimmer, he's been reporting on this and also has a new book called Life's Edge: The Search for What It Means to Be Alive. Carl, thank you so much.

Carl: Thank you.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.