Louis Auchincloss Talks About His Manhattan

Publishers don't usually like printing collections of short stories, the well-known lawyer and author confides in this 1967 Book and Author Luncheon. While people read stories in magazines, they are reluctant to buy them in book form. This may be because they have to "change gears" as they go along, adjusting every few pages to new settings and characters. To combat this, Auchincloss has provided several "common denominators," easing the transitions between the stories in his most recent collection, Tales of Manhattan. The first five stories are told by a worker in an auction gallery. (New York is the art capitol of the world, he argues, not because so many artists live here but because there are so many dealers.) The second four are told by members of a law firm. Here he pauses to defend his use of first-person narration, claiming he sees nothing artificial in having a character "tell" you his story. The third grouping centers on society matrons, "my cops of high society." This last section includes the text of a play. He talks about being bitten by the theater bug and how, after many years of trying, he finally saw this one produced and found the experience of listening to his own words "intoxicating." He went to every performance, thus proving correct the advice once given him by Gore Vidal: "If you want to enjoy a play, you must write one." He concludes with a paean to the book's true common denominator, Manhattan itself. Or rather the Manhattan of Auchincloss' very exclusive world: "Old-fashioned, largely gone, but lingering in every store and under every auctioneer's gavel."

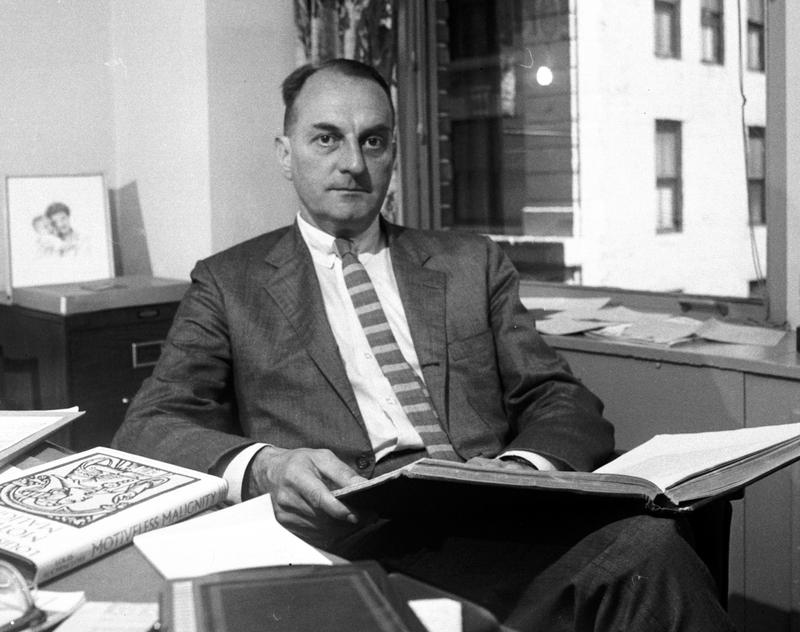

Louis Auchincloss (1917-2010) was inextricably associated with the world of upper class wealth and privilege. Yet the phrase "idle rich" is the very opposite of how one would describe him. As the New York Times pointed out:

Although he practiced law full time until 1987, Mr. Auchincloss published more than 60 books of fiction, biography and literary criticism in a writing career of more than a half-century. He was best known for his dozens and dozens of novels about what he called the “comfortable” world, which in the 1930s meant “an apartment or brownstone in town, a house in the country, having five or six maids, two or three cars, several clubs and one’s children in private schools.” This was the world he came from, and its customs and secrets were his subject from the beginning. He persisted in writing about it, fondly but also trenchantly, long after that world had begun to vanish.

This chosen subject made Auchincloss something of an outlier in the literary world. While some praised him for examining a largely ignored or at best caricatured stratum of society, others found his world narrow and snobbish. There was, critics seemed to imply, something inherently undemocratic, even un-American, about investing the morals and mores of the super-rich with such literary importance. The contrary view was expressed by Auchincloss' fellow WASP aristocrat (and distant cousin) Gore Vidal, who was quoted in the Guardian newspaper as arguing:

Of all our novelists Auchincloss is the only one who tells us how our rulers behave in their banks and their boardrooms, their law offices and their clubs.

But Auchincloss was hardly a blind defender or booster of his class. While accepting, indeed embodying, many of its principles, he also provided in the very act of writing fiction a subversive insider's view of the ruling class that had so enduringly composed the social life of "his" Manhattan. This tension between sincerely belonging and possibly contributing to its collapse is what informs his best work. It is the same tension one senses in his dual professions. As he told the alumni magazine of his alma mater, the University of Virginia School of Law:

“I used to go to all the Saturday night parties with the other young lawyers. They talked all the time about whether they were going to be a partner; I thought here was a whole room of my friends who were all terrified they might not be partners; I was terrified I might be one.”