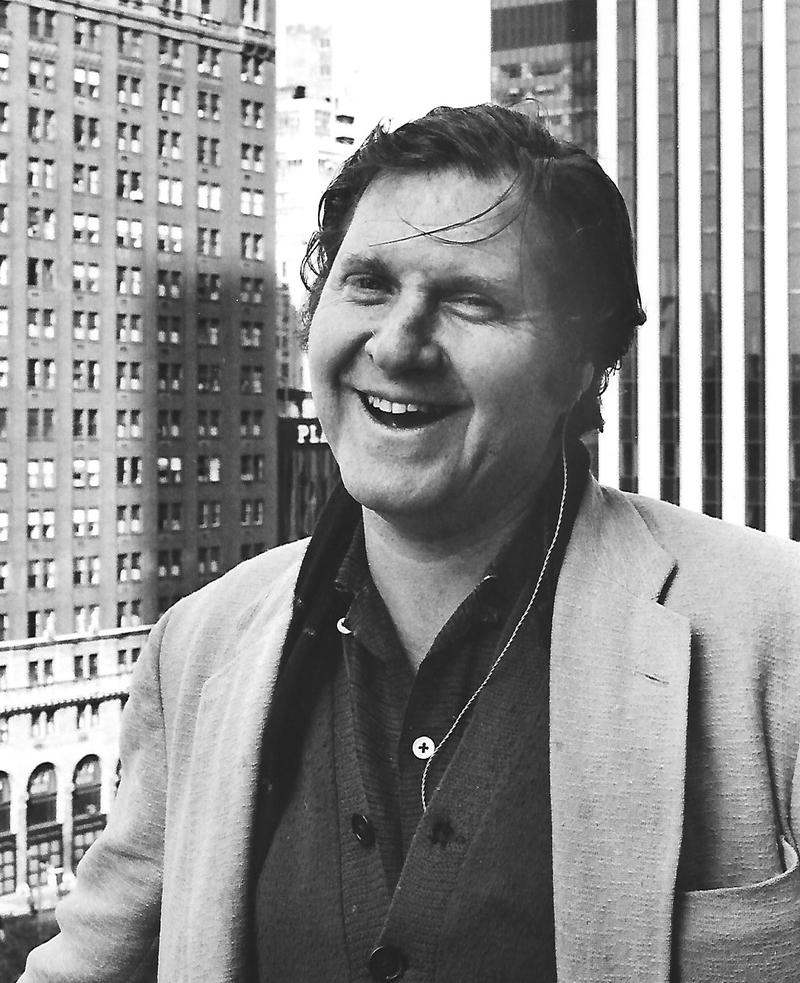

( Tom Gervasi )

Writer Marvin Cohen discusses his seventh book and first novel, Others, Including Morstive Sternbump, published in 1976.

WNYC archives id: 72866

Reader's Almanac

WNYC 93.9 FM

December 14, 1976

Marvin Cohen discusses his seventh book and first novel, Others, Including Morstive

Sternbump.

ANNOUNCER: From New York, publishing capital of the world, we bring you the Reader's Almanac. These programs are dedicated to good reading and to the people who produce good books. And now

by transcription, here is the editor of the Almanac, Walter James Miller.

MILLER: As Marvin Cohen has published six books of small fictions and essays and other pieces, it must have occurred to many entertained and edified readers that they'd like to read a full-length novelby Marvin Cohen. Happily, the same idea has occurred to Bobbs-Merrill and they've had the good sense to bring out Cohen's seventh book and first novel. It's called Others, Including Morstive Sternbump. The tragicomic ups and downs of Morstive Sternbump will please all of Cohen's following and even create new followings, which means that New Directions better be ready for a revival of interest in The Monday Rhetoric of the Love Club and Links Books had better expect the new demand for Baseball, the Beautiful, because readers discovering Marvin Cohen through this new novel will soon fan out looking for his earlier books.

Others, Including Morstive Sternbump is, like most Cohen writings, a parable — I guess I should say an allegory since this time he's doing it at full novel length — and it's chock full of the Cohen sentences that everyone first chortles over and then plagiarizes. Firstly, allegory. The cast of characters in Others, Including Morstive Sternbump significantly includes a clergyman in search of a divine son, several politicians and other sports promoters, businessmen in their endless power struggles to be king of the hill, several women caught in the various traps that patriarchal society gives them a generous choice of, and a central character who fails in the outside world and then has an interesting evolution as a person and as a writer. For example, when he tries to write directly from his own experience, he fails. But when he imagines himself as a writer writing of that experience, he succeeds.What carries us through this philosophical allegory is Cohen's mastery of the epigram, the aphorism, the pun, the quotable sentence. Not even Sam Beckett can outdo Marvin Cohen in that telling sentence in which the character first constructs an idea and then dismantles it. My favorite Cohen

sentence is one I use all the time when I want a raise:

"

I have moved from working class background to working class foreground."

The futility of life, especially when it's self-imposed, is perfectly captured in that type of Cohen sentence. Take for example this passage about Sternbump found, of course, in Sternbump's own self

reflections:

"

Part of him was social, and only the personal part was not. And even that privately

t

ried to be conspicuous for what would people think of him otherwise? If only a

mir

ror were there, he would have seen himself, not as others saw him, but as others

w

ould be made to see him. Not that he cared. Of course not. He was too independent."

Again, on page 4:

"

... his judgment of himself was low. And he valued people according to the way

t

hey dismissed him, approving their sound taste in giving him the go-bye. Which

h

e deserved. When people recognized his inferiority, they were superior. He himself

wa

s superior, for he knew of it better than they. So he prepared to be nervous, against tomorrow night's disaster."

And Cohen's nervous characters are always revising a generalization as soon as they make one. For example, Jessup Clubb typically thinks fun is always welcome at times. Such constant self-revision keeps a Cohen character hunched in his low profile. What I'm saying is that Others, Including Morstive Sternbump is a sustained allegory of unbearable urban life made bearable by unfailing love of language, which makes us happy that Marvin Cohen is here with us at the microphone. Congratulations, Marvin Cohen.

COHEN: Boy, I really like the way you spoke about the book. In fact, you spoke about the book so well,

I hereby abdicate all my remaining time.

MILLER: Marvin, how did it feel after publishing six collections of small fictions, suddenly to have all

this galactic space of the novel to roam in?

COHEN: Oh, I loved it! Boy, it's great to really develop something and develop something. One of the limitations of the short form is that you've got to hit right out and not take it too far, but take it logically, bring it through a transition and a development and then, bang, end it and the end is within sight of

the beginning. But a novel or any lengthy work, the end is not within sight of the beginning and so it's like going over a big country on a hike, on a trek. You don't quite know what's beyond what you're

immediately seeing in the near distant horizon. And a novel goes places and you have flexibility so that, even as you're having fun right now with a few words and a few characters and you have to be disciplined about them, still there's possibility for radically different things happening later. You can change your pace. There can be a seventh inning rally. There can be unexpected detours that would nevertheless get resolved well afterward.

MILLER: Your action emphasizes the turn of the seasons. You come back to New Year's and to other

holidays, and Jessup Clubb, one of your characters, seeks to become, as I see it, the sacrificed god. He always ready to martyr himself, and he's always trying to have a child through Merlin-like circumstances. Are you prepared for what the anthropological critics are going to make of these variations on the

fertility cycle?

COHEN: Oh, I sure am. One reason why I'm thoroughly prepared is that I don't know what they're going to say, and so that arms me to the teeth. By the way, what do you mean by Merlin-like circumstances or fertility rites and so forth?

MILLER: Well, you know, all of the great heroes — King Arthur himself, Merlin who managed the special birth of King Arthur — all of these great heroes must have some kind of mysterious birth, and here we have Jessup Clubb who's trying to found a new religion in your novel, and trying to martyr himself so he

can be the sacrificed god. He's also looking for a child, but it must not be in the normal manner. It must be engineered in some special way.

COHEN: In some special way, yeah. Well, Jessup Clubb was my satire, takeoff, on that old historical figure, Jesus Christ, who is really the central pivot for Christian religions, whether they're Methodist or Catholic. But all the world knows about Christianity. I wanted to do a sendoff on it. Is "sendoff" used in America? It's used in England.

MILLER: I suppose we usually call it a "takeoff." Have you become that British?

COHEN: Sort of. Yeah. Very.

MILLER: You think of "sendoff" instead of "takeoff." That's interesting.

COHEN: Yes, except that it doesn't quite mean takeoff. But anyway, I thought of Jessup Clubb as a man who had an overwhelmingly Christ complex — no, I mean an "overwhelming," not "overwhelmingly" Christ complex — and he wanted to give birth to a Christ figure, namely himself, to perpetuate himself, and he wanted to be a martyr, and he was terribly masochistic but he was also perversely cruel which the historical, mythical Christ certainly was not. And he actually had a lot of actual real things to do with women which the historical, mythic Christ was reputed never to have done. And so I hope that practicing and believing Christians don't get too mortally offended and I hope I'm not assassinated by a really

militant Christian. Except that a militant Christian, what would he be doing reading a book like this?

[Laughter]

MILLER: About Morstive Sternbump. I can understand Morstive Sternbump's last name but now that I've mentioned King Arthur and Merlin, I must tell you that when I thought of his first name, Morstive, I thought of a kind of restive Mordred, or Mordred the restive. What did you have in mind when you thought of him?

COHEN: Well, for the benefit of the listening audience, Mordred was the son of a bitch who killed King Arthur. But of course, it was just aesthetically appropriate that King Arthur came to his end that way so we owe a lot to Mordred. But, anyway. Oh yeah, what was the question?

MILLER: How did you decide on the name Morstive?

COHEN: Oh yeah. That's right. What a detour. [Laughter] By the way, it's possible to go on a detour without driving a car. Anyway, well, I wanted a funny name so it's sort of funny, but I wanted a name that wasn't totally out of the feasible, plausible range, and I wanted a name that sort of was a bit Semitic, which Morstive Sternbump is. And I think that the name Morstive with a "V" in it, and with an "R" in

the middle and beginning with "M" is sort of a satirical takeoff on the strange name of Marvin.

MILLER: Your takeoff reminds me of our sendoff discussion and I guess what shocked me when you asked that question about American idiom is that one of your best books is called Baseball, the Beautiful.

COHEN: Yeah.

MILLER: Not cricket.

COHEN: But I wrote about cricket in England.

MILLER: You did?

COHEN: Yes. And I love cricket in England when I'm there. I go there most summers and adore it,

and baseball I adore here. I'm a great Yankee fan. And by the way, I made Morstive Sternbump into a Yankee fan, but the listener to this Reader's Almanac is not to get the idea that Morstive Sternbump is really based on me. I hope not because, for one thing, if I'm really to be seen as Morstive Sternbump,

then people may look a little bit down at me and make me seem a little bit ridiculous or humiliated. It's not true. I just made a kind of heroic, pathetic hero anti-hero who has a lot of feelings and doesn't know quite how to reconcile those feelings with the conditions and circumstances in the world. Because you can't really control other people and you can't really get what you want done in the world.

Objects object, and the world is full of objecting objects, and here was this hero who was up against the world of other people, mainly, mostly people who were crasser than he and who had a less broad, less philosophical, and less humane outlook. In other words, Mortive Sternbump was with a lot of characters who were more limited than he was. And in a way, their strength was in their limitations because they were able to come to convictions and to opinions which Morstive Sternbump couldn't really allow himself to come to because he saw always two or three sides to the same thing, so he was flustered at a loss. At every step he took a few steps backward.

MILLER: Yes, that's a good description of Morstive Sternbump. You're familiar with him. [Laughter] That is his strength and his weakness. He is at a disadvantage with anyone of narrower interests and narrower sympathies.

COHEN: Yeah. By the way, it's interesting that when a novel is based around a central figure who is almost the first person, except that it's narrated in the third person, the central figure is seen less clearly than the secondary figures so that, really, every other character in the book is seen with a sharper

delineation and a more definite depicting than the central character, Morstive Sternbump. The same

is true of Marcel in Proust's enormous novel. Marcel being really the personification of the author was very amorphous and you couldn't really quite get a definite picture of Marcel, but Proust was able to be very satirical about all the secondary characters.

MILLER: Well, I think Morstive comes across more morphous than that.

COHEN: More amorphous than that?

MILLER: More morphous.

COHEN: Oh, more morphous.

MILLER: I'm dropping the "A" from the amorphous.

COHEN: Oh, that's interesting. I like that.

MILLER: He's not amorphous, which is to say he's not an autobiographical character.

COHEN: No. He could almost be Mister Everyman today updated. Mister Everyman, a man who really has a good heart in the world and wants to bestow good wherever he can, whatever his resources are, beginning with himself — his charity begins at home — has good will and good faith toward the rest of humanity, but he is not well cooperated with by women or other people or employers. Somehow he's stymied and stifled but yet he means well, and that is a tragedy and that is a comedy right there.

MILLER: Yes. I imagine that some critics are going to try out their ring of keys on your novel because they'll swear it's a roman à clef.

COHEN: Hmm.

MILLER: The political figures, for example, they are apt to be heavily analyzed for parallels. Don't you think?

COHEN: Oh yes, but they can analyze the political figures to doomsday and still come up with different conclusions as to who the originals were. I had no particular political figures in mind except a montage, cynically seen, of the worst in statesmen and politicians. Somehow, being in the public realm brings out the worst. Being in a power realm brings out the worst in an individual. The individual characteristics that we most value are often undermined and distorted and warped when somebody obtains political prominence and power, whether in business or in any authoritarian setup.

MILLER: That happened to Morstive himself.

COHEN: Oh yes. That's right. He himself tried to get power because he hated always being poor and down, and one reason why he wanted to be a successful businessman and make a lot of money and to

do whatever he could, even become mayor, was it would make it easier for him to be admired by women. Now, the book was written in 1960 when women were harder to come by for a well-meaning chap. In 1960, the morals were a little different.

MILLER: Yes. I think women among your readers are apt to find here a very thorough allegory of the dismal spectrum of alternatives that our great city offers them.

COHEN: Wow. Now would you care to elaborate on what you mean by dismal spectrum of alternatives?

MILLER: Well, most of your women characters in the sixties in the city of New York, and it's probably

still true today, see marriage or some other alliance with a man as still their main hope.

COHEN: Yeah. That's right. Otherwise, if they don't marry, they have to carry on being office

secretaries or typists or clerks or teachers or whatever, and a lot of it is dull business and unglamorous.

A lot of women wanted power but the roads to power weren't as accessible as they are today. This was 1960 that the novel was really situated in and so women often would identify with a man's ascension

to prominence and eminence. So this gave men more incentive to make good in money and power so that then because, in a way, it's like a pregnant soon-to-be mother is eating for two. And so it is that the man in those days was getting the power and the glory for his women as well as for himself.

MILLER: Yes. Would you tell us what's new in the works now? This is your seventh book?

COHEN: Yes.

MILLER: And you had a CAPS award recently?

COHEN: Yes. A CAPS award. Do the readers, I mean, do the listeners know what that is?

MILLER: Will you tell us what that acronym...

COHEN: It means Creative something or other, something or other, something or other.

MILLER: Creative Artists in the Public Service.

COHEN: That's right. Thanks for helping me out. I really needed it. Boy!

[Laughter]

MILLER: Which is what you are at this moment.

COHEN: Yes. It's New York State funded. I won 4,000 smackeroos which came in handy and I gave a

little dedication to CAPS in the beginning of it. I'm working on lots of things: novellas, parables, fables, short things. I would like to do another novel but I need help. One reason why I need help is because I can't see it all. I can't see it all. Some guys have a sense of form where they can see the beginning, middle, and end. I can only see the beginning, middle, and end in a short piece. It makes more coherent sense. But a novel has a danger of sprawling because it's over rough country, and over hills and dales, and into towns and hamlets and farm communities, and you don't know what's going to be. Maybe there'll be a desert, maybe there'll be an ocean over the horizon.

MILLER: When you say you need help, what do you mean? Your writing students come to you for help. To whom do you go?

COHEN: Well, let me tell you. Tom Gervasi is the managing editor of Bobbs-Merrill and he helped this book to see light. In fact, I dedicated the book to him. What does the dedication say?

MILLER: It says "To Tom Gervasi, who helped this book see daylight."

COHEN: That's right. Well, he did because he took it … it was a loose, sprawling baggy monster in the words of Henry James, a little distorted. In fact Henry James accused Tolstoy of all people of creating a loose, baggy monster. Now we think differently. But Tom Gervasi got this manuscript from me and he put it all together. He told me what to rewrite and he firmly made deletions, and he deleted the parts

that didn't quite belong with the rest, and then he forced me to rewrite it and so I owe it all to him.

MILLER: That's a marvelous kind of editor to have. I have an editor like that, too. That makes two.

COHEN: Oh, good. I'm glad for you. I heard that Thomas Wolfe had Maxwell Perkins. I heard that

editors like that are a bit rare these days.

MILLER: Yes. They're more likely to reject. I'm not saying that your stuff and mine is rejectable without this kind of help. It's simply that you do come out with a better book. I have a book out now which I'd

say I added about 10,000 words after I thought I was exhausted. I added about 10,000 words because

my editor made so many good suggestions that I was just re-inspired.

COHEN: And did your editor welcome and accept those extra 10,000 words?

MILLER: Yes. Constructive editing is what you're describing.

COHEN: How did you feel about the annotation of the Jules Verne A Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, although aren't we reversing this interview?

MILLER: Yes.

[Laughter]

COHEN: How did you feel when you wrote it? How did ...

MILLER: Good for you to take over. Well, there we have two editors, at least two that I've heard of. Mine is named Hugh Rawson incidentally.

Well, thanks, Marvin Cohen. I'm cutting in to make sure that I get time to remind our listeners

of the basic facts they'll need to follow through, because we do want them to buy the book and know what it's all about. We've been talking with Marvin Cohen about his seventh book and his first novel called Others, Including Morstive Sternbump. This inventive and entertaining allegory of today's urban

life is a new publication of the Bobbs-Merrill Company Incorporated. Others, Including Morstive

Sternbump was written partly with support from the Creative Artists in Public Service program. Thank you, CAPS. Thank you, Bobbs-Merrill. Thank you, Tom Gervasi. And thank you to New Directions and Links Books, publishers of my favorite earlier works by Marvin Cohen.

If you have any questions about Marvin Cohen's books, his publishers, anything we discussed

tonight, please write to me care of this station. This is Walter James Miller of New York University's School of Continuing Education, which produces this program as a public service.

ANNOUNCER: You have been listening to the Reader's Almanac with Walter James Miller. We're

interested in your reaction to this evening's program. Address your comments to Reader's Almanac, WNYC, New York, 10007. And join us again next week at this same time for the Reader's Almanac,

a winner of the Peabody Award.