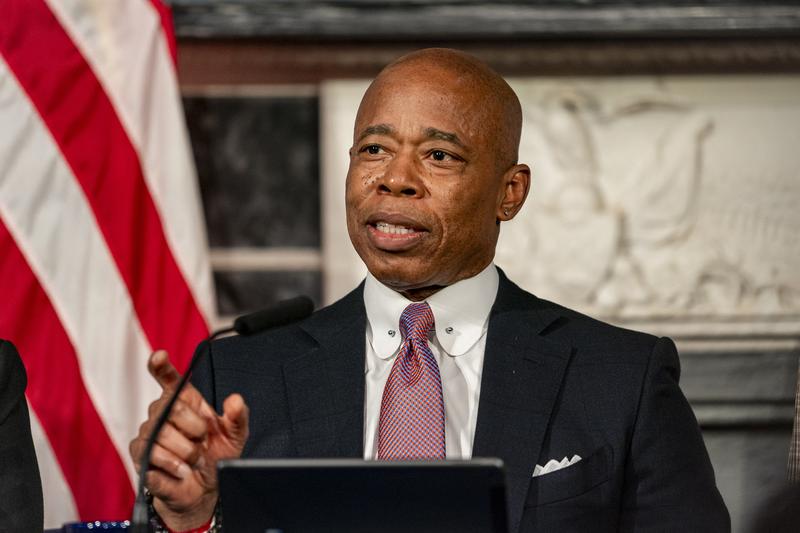

( Peter K. Afriyie / AP Images )

Greg David, contributor covering fiscal and economic issues for THE CITY and director of the business and economics reporting program and Ravitch Fiscal Reporting Program at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism, examines the cancelled spending cuts and the mayor's management of the budget.

→"How Adams Played City Budget Numbers, Conjuring a Crisis" (The City, 1/17/24)

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Next this morning, a tough take on Mayor Adams and the New York City budget, accusing him of conjuring - and that's the word, conjuring - a fake crisis that has resulted in libraries closing on Sundays and other cuts that were threatened and then not implemented.

This comes not from a progressive opponent on City Council as you might expect to hear, but from journalist Greg David, business and economics reporter for the news organization THE CITY and head of the business and economics reporting program at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY, who is known to be an independent thinker in his reporting, and who cites multiple independent sources who know how budget making and budget fudging work. Greg's latest article in THE CITY has the damning headline How Adams Played City Budget Numbers, Conjuring a Crisis.

Now, by way of background, here's a clip of the mayor on Fox 5 last week arguing that the crisis he announced in November was real.

Mayor Adams: "What we did in November, we identified the problem. It was believed, as I stated last year, we were going to have 100,000 migrants and asylum seekers in our care with a cost attached to that. Instead of 100,000, it ballooned to 168,000, so we had a two-pronged attack. Number one, we had to be able to pay for that, but number two, we needed to start a process of cycling them out of our care."

Brian Lehrer: The mayor on Fox 5 last week. With us now, Greg David from CUNY's J-School and the news site THE CITY. We'll also touch, by the way, on a new initiative announced by the mayor to relieve half a million New Yorkers of medical debt. Hi, Greg. Welcome back to WNYC.

Greg David: Thank you. I hope I live up to that introduction.

Brian Lehrer: Well, make your case regarding the first part of that Mayor Adams clip that what he said in November about a city budget crisis was disingenuous, according to your article.

Greg David: Let's understand that the situation in November, the mayor made look as bad as possible. He said there was a $7 billion budget gap for the fiscal year that begins July 1st. That's a big budget gap to close. In understanding the assumptions that went into that, early in 2023, most people thought there would be a recession. The high interest rates that the fed had driven up to deal with inflation would result in a recession, which would cause unemployment to rise and tax revenues to plunge.

However, by November, it was clear there would be no recession, tax revenues were running much stronger than anticipated. and most people were raising their tax revenue forecasts, but not the mayor. The Adams administration didn't change the economic assumptions at all, so they underestimated the amount of tax revenue that would be coming. The second thing that was going on is that there were a number of-- people were complaining all along that the administration was not clear on the cost of the migrant care, and that the estimates were being inflated. Well, they were inflated.

Now, the mayor says that's because of their great management skills, but in November, the asylum seekers' cost over three years was $12 billion. By January, it was $10 billion. You've got $2 billion more in tax revenue, $2 billion less in expenses for asylum seekers, and lo and behold, we don't have a crisis. The way I framed it at the top of the story is in November the sky was falling on the budget, in January, it was not, and virtually all the high-profile cuts that the mayor had threatened in November have now disappeared from the agenda.

Brian Lehrer: If I'm reading your article correctly, there were respected others who were saying at the time that the mayor's budget forecasts that necessitated the projection of all those cuts was overblown. You cite the Independent Budget Office and other fiscal watchdogs, but the Independent Budget Office, which I guess was set up after the fiscal crisis of the 1970s in New York City, is known to be independent. It says it took into account the better-than-expected economy and foresaw much smaller gaps to be closed. Was this an open debate in November, and I guess by extension, did a lot of the media miss that open debate?

Greg David: The trouble with it was that the raised revenue forecast came a little bit after the mayor got all the attention in what's called his November modification. The person doing most of the screaming was Justin Brannan, the head of the Finance Committee. It was portrayed as a political event.

Brian Lehrer: I think also the Comptroller, Brad Lander, who we had on at the time.

Greg David: That's true, although his official forecast was, again, a couple of weeks later. It was portrayed as a political battle between the moderate mayor and the progressives in the council. There's one other important thing here because basically, the issue here is the credibility of the administration on budget and fiscal issues. That was the mayor has been pounding away on what we call PEGs, Programs to Eliminate the Gap. One of the things that happened in November is the budget director announced - or a little before November - that there would be three PEGs, and every agency would have to cut their budget by 5% every three months.

Well, the IBO did a survey of former budget directors, and none of them could remember a PEG program like that. There's a reason for that. PEG programs are designed to force agencies to improve their efficiency, so you don't want numbers that high and you don't want the time period to be that short. They're not designed to do these overall budget cutting. That should be done by identifying programs that you don't want to continue or can't afford to continue. All of this has undermined the credibility of the administration, and I think that's an important point to make.

Brian Lehrer: Let me ask you to go back to a number that I think you cited a minute ago and be specific and elaborate on it a little bit because I think our listeners would find it really interesting. Were you saying there is a real knowable number that reflects the amount of additional costs to the city, to the taxpayers of New York City, from the number of asylum seekers who've come in the last two years?

Greg David: Is there a real knowable number? No, there isn't a real knowable number. People were arguing all along that the per-daily cost the administration was estimating for the asylum seekers was way too high. Indeed, the administration has brought that number down. Brian, I think there's another number that everybody should focus in on. $10 billion to care for asylum seekers over three years, is that a lot of money?

Brian Lehrer: I was just going to ask you that because the city budget is $109 billion a year. If you're talking about $10 billion over three years, roughly $3.3 billion per year on $109 billion, it's about 3%. You tell me, is that a lot of money?

Greg David: No. I've been trying to make this point for a long time. Look, $10 billion is a sizable amount of money, but 3% of the budget is not that big. Look. Would you like to have that money to spend on something else? Of course, but this gets us back to this whole argument the mayor's made. His most famous quote is that the asylum seekers were going to destroy New York.

Brian Lehrer: Right.

Greg David: He didn't specify in what way they were going to destroy New York, but the most charitable thing you could say is that they were going to destroy the budget. The context tells us that it was a problem, but they weren't going to destroy the budget. More broadly than that, and a lot of people from the progressive side had been making this point, and I tried to make it in a story I wrote over the summer, immigration has been crucial to New York.

Our economy, our broad-based economy, our boom in the tourism sector, our revival of neighborhoods that were in bad shape in the 1980s, it's all based on immigration. Immigration is good for New York. Indeed, you walk around the city these days and you walk into stores and they've all got hiring signs. Now, yes, there are a lot of bureaucratic hurdles to integrating asylum seekers in the economy, but they are not destroying New York. Indeed, long-term they could be a great benefit to the city.

Brian Lehrer: How long does it take for cost to fall on the plus side of the ledger, if it's even possible to answer that question? If this many asylum seekers-- so far about 170,000 in the last two years, I believe, is roughly the number. If it's costing the city $3 billion a year to settle them at the moment, when does it become an economic plus for the city based on all those long-term factors you were just mentioning?

Greg David: I don't know. That's a good question. I think Brad Lander should give us an answer because he did a very good-- If you really want to know, he did these great myths about immigrants that the Comptroller's office published in December. I'd refer everyone to it. It's got all the economic underpinnings of why immigration is good. Maybe they could do that study, so I don't know a specific answer for it.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. Listeners, we can take some phone calls for Greg David, head of the business and economics reporting department - I don't know if it's a department - at the news organization THE CITY, as well as the business and economics reporting program at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. 212-433-WNYC on his new article on THE CITY news site. That's not the City of New York. It's always incumbent on us to explain the difference. This is the independent not-for-profit news organization called THE CITY. The article called How Adams Played City Budget Numbers, Conjuring a Crisis.

We can also take your calls on something that I think he's going to like that the mayor is doing, announced yesterday. Initiating a program to relieve medical debt for about half a million New York City residents. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Call or text.

You speculate in the article that the overestimate of the fiscal crisis could have been to help the mayor pressure Washington to send more financial aid to the city since immigration is a national function and Washington is really causing this. That's a fair argument by the mayor, but it turned out to be based on false numbers now corrected. Where does that leave us with our pleas to DC?

Greg David: Well, I think the mayor decided there wasn't going to be any aid, and I think that's pretty clear there isn't going to be any aid. Considering the session you had before and what's going on in Washington, why are Republicans going to send--

Brian Lehrer: Yes. The Republicans would have to authorize it in the House, and they're not going to do it.

Greg David: They're not going to do it. I think by January, the mayor gave up on that. But another important thing happened between November and January, and that was his poll ratings tanked. It became clear that the budget-cut seeds proposed were wildly unpopular. There were people who told me I wrote the wrong story. That the story I should have written was that the long-term budget problem for the city is serious. I agree with that, by the way, but it seems to me that the mayor's handling of the budget has undermined people's ability to make that argument.

I saw Councilwoman Cabán's statement the other day that this is an austerity budget. Well, it's not an austerity budget. If you're going to convince the public that New York City has a long-term budget problem, that we are spending too much and our revenues cannot support it, you can't do this with [unintelligible 00:13:39], which is what someone complained to the mayor about in a press conference, and have credibility with the voters that you're doing the right thing by them.

Brian Lehrer: Why do you say New York is facing a longest-term financial or fiscal crisis?

Greg David: Well, because we've increased spending dramatically as a beneficiary of the fact New York did so well in the pandemic in terms of what wealthy people earned. Income tax revenues went up. We used federal aid and boosted the budget, sometimes in fiscally irresponsible ways. We face significant budget problems in the coming years, and that is a fact.

Brian Lehrer: Well, let me ask you a bigger New York City and New York State budget question then, which is really beyond the scope of the article you just wrote and probably needs its own segment. Not just a question within this segment, but the city alone has a budget of more than $100 billion a year. Which is about the same size as the whole state government of Florida, which has twice as many people. Our state budget is on top of the city budget, another $200 billion-plus while Florida, again, a few more people than New York State, has half the state budget.

Is there a New York, Florida value for our tax dollars comparison to be made here? It's probably really complicated and would take a lot of drilling down on a lot of specific services, but maybe services in Florida are just that bad or maybe we spend too much to get too little. Do you have a take?

Greg David: Yes. Can I answer that both are true? Look, I wouldn't want to live in Florida. The safety net is terrible. We have a safety net that helps people a lot, and that's a good thing, but we also have enormous spending. We spend more on education than anyone else. We spend more on Medicaid than anyone else. Ask people who study government. Our government is not very efficient. The answer is both. We spend too much, but no, I would not want to be living in Florida myself.

Brian Lehrer: 212-433-WNYC. Nick in The Bronx, you're on WNYC with Greg David. Hi.

Nick: Hi, Brian and Greg. Thanks for taking this call. I wanted some clarification on the percentage of costs for serving new arrivals, new immigrants in New York City. You said it was about $3.3 billion a year, which is a fraction of the overall city budget. As I'm looking at the PEG number that the IBO explains, it says that there's about a $2.3 billion PEG that the city is looking at, which is--

Brian Lehrer: That was the reduction just to get past the alphabet soup. That's the amount of reduction that the mayor was asking the city agencies to take.

Nick: Right. I know we need to serve new arrivals and this funding is important, but I'm trying to understand how the expenses that the city is cutting are connected to increased costs, including the need to serve new arrivals.

Brian Lehrer: Can you understand the question, Greg?

Greg David: Yes. I think the answer is that's the way the mayor portrayed it. The PEGs were designed to rein in spending and then to help us pay what we need to do to deal with the asylum seekers. The trouble is the city's budget problem is not based only on the fact that we have this new asylum cost. As a matter of fact, there are three major fundamental problems in the city budget. The asylum seekers' cost is one. The second one is that we used COVID money to fund recurring programs like the expansion of Pre-K to three-year-olds. Well, the COVID money has run out, and now the question is how are we going to fund the expansion of Pre-K? That was the second major problem for the city.

The third major problem which the city has inflicted on itself is that some programs, including housing vouchers, that the council and the mayor have funded for only one year. Each year you have to decide whether you're going to continue the funding or find new revenue. Those are called fiscal cliffs. In addition to the asylum seekers, the city undertook budgeting maneuvers that meant that we would have deficits if we wanted to continue to run those programs. Both are complete no-nos in good budgeting, but we did it anyway.

You can't really match up the PEGs to the asylum seekers. As a matter of fact, you shouldn't try. PEGs should be used to force agencies to be more efficient, not to cut the budget.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for your question, Nick. Where did the budget cuts actually fall? The real budget cuts, not the fake ones that you said the mayor conjured in November. The smaller number that he actually implemented once he said the projections were rosier than he originally thought. The thing we hear, and I feel like it's the only thing we hear, is the libraries had to close on Sundays. Where else did they fall? Anywhere?

Greg David: It's very hard to track it. Brian, can I give you one of my budget cuts lessons that I drum into the reporters around the country who come to the J-School for-

Brian Lehrer: I'm enrolling.

Greg David: -advanced training on this?

Brian Lehrer: I'm enrolling for this answer.

Greg David: What does the word budget cuts mean? When you and I cut our budgets, we reduce our current spending. Right?

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] I think I know what you're going to say. Smaller rate of growth. Is that where you're going?

Greg David: That's what it means. Budget cuts in government mean cuts from what I expected to spend. Here's the best example of it. When the Republicans were trying to repeal Obamacare, the Democrats argued that hundreds of billions of dollars of healthcare spending would be cut. The Republicans said no healthcare spending would go up every year. Who was right? Both of them.

Brian Lehrer: Professor David, inflation is real. Just to keep services steady, spending has to go up each year. Right?

Greg David: That's true. Although when inflation is at 2%, that's a more modest problem than 9%. Yes. The way that inflation has affected the city budget is that we've signed relatively lucrative contracts with our labor force for the next four years, and we're going to have to pay for that. The question out there is whether revenues will keep pace. That's a legitimate question, and we will have to see.

Brian Lehrer: We are in New York and New Jersey Public Radio. We are on the New Jersey side in our first segment with Congresswoman Mikie Sherrill from Northern New Jersey. We're on the New York side with Greg David from the news organization THE CITY and the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY, and you at 212-433-WNYC for another few minutes. I want to do two things in our remaining time. I want to touch on this new medical debt relief program that the mayor announced yesterday, but I also want to get your take on a segment that we had last week.

I don't expect you to have heard this segment, but on this whole issue of an urban doom loop, which is another projection of crisis-level economics in New York City where another person, this time a professor from the Columbia Business School, was projecting all kinds of extraordinary Armageddon-level finances in New York City because the value of all the office buildings was going to crash - or many office buildings - because of remote work. That would kill tax revenues for the city, which would make them kill a lot of services for the city. A lot of people would move to New Jersey and Connecticut, maybe even Florida. Now he comes back and says, "Well, maybe not so bad."

Is this something-

Greg David: Yes, maybe not so bad.

Brian Lehrer: - you've looked into?

Greg David: Yes. I teach this stuff too. You just enunciated the doom loop that he has articulated. There's no doubt that office buildings in New York are going to be worth a lot less, many of them, and tax revenues are going to suffer. The question is how much? What we're seeing in New York, and the Comptroller has made a run at this, and the IBO's done some work on this, is that the best guess at the moment is that tax revenue will-- it'll cost us about a billion dollars a year in tax revenue. We've got the same percentage issue here, right?

Brian Lehrer: Right.

Greg David: A billion and $110 billion budget. We'd like to have that tax revenue, but it isn't leading to a doom loop.

Brian Lehrer: "A billion here, a billion there," someone once that. All right. Medical debt. Have you looked at this new program that the mayor announced yesterday in conjunction with a nonprofit?

Greg David: Yes. Extraordinary numbers, huh? We're going to wipe out $2 billion in debt by spending $18 million. How is this possible? I had back surgery a couple of years ago, and I actually looked into the bills. The surgeon billed my insurance company about $10,000 and got about 3,500. The hospital wound up billing $40,000 and got less than $10,000 because my insurance company negotiates enormous discounts. If I were uninsured, the hospital would have billed me the entire $50,000 and tried to collect it from me. Of course, if I was uninsured I probably couldn't pay it.

Hospitals are carrying this enormous debt as something they're owed, but they know they're not going to collect. That's why the hospitals are willing to sell $2 billion in debt for $18 million. It will really improve the finances of the people who qualify because all that debt will be wiped off their books.

Brian Lehrer: The numbers--

Greg David: It's a good idea and we should do more of it, but it does show how crazy some of the hospital medical systems we have that I, who actually, if I absolutely had to, could pay the $50,000, had to pay no more than $500 for my surgery. If you are uninsured because you can't afford it, you're going to be asked to pay the whole freight. It makes no sense.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Anybody who's insured, who's looked at their explanation of benefits from their insurance company, sees these bills. You go in for some routine thing and it's $1,973, and then your insurance pays everything but $20 of it because a lot of that is just a negotiated discount. Still, the number being reported is this is going to help 500,000 New Yorkers. That means a lot of New Yorkers are uninsured and needs the government plus this nonprofit to do this negotiating for them. Correct?

Brian Lehrer: Correct. I would say that New York has driven its uninsured rate well down below 10%. I think if you get sick and you're uninsured, or you have lousy coverage, you could be saddled with a lot of debt, and it's a good thing. We should be doing this. We should be making hospitals do more. In New York, they're all nonprofit hospitals. They don't pay any taxes. They pay their CEOs millions of dollars a year and they don't actually do much charity care. The hospitals are getting $18 million that maybe they would've gotten, but probably they wouldn't have gotten, and it's going to be good for those 500,000 people, that's for sure.

Greg David: I want to get two callers in before we run out of time. Arthur in Bayside, we see you on the healthcare profiteering relevant to what we were just saying. I want to get Christina in Flatbush in here first, which goes back to our passing comparison between the services and the tax rates in New York compared to Florida. Christina, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Christina: Hi, Brian. I love your show. I found the comparison really interesting because I just returned from Florida two days ago. I was there for work for two weeks, and I have to say it was pretty dystopian. When I was taken around by the person who was hosting me, every park she showed me was privately funded. She spoke about public schools very disparagingly. Like, "Oh, who could possibly send their kids to public schools? The public schools are horrible."

People were appalled when I spoke about the fact that as an artist, I'm an opera singer, and as a freelancer, that I do have insurance. I have to say that I think it's not a great comparison because even just being there for two weeks, I couldn't believe how few public services were offered in Florida and how much better my quality of life is just as a New Yorker.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for that anecdote. I appreciate it. This is a long-time labor leader, Arthur Cheliotes, calling in. You probably know each other. Arthur, you're on WNYC. You've been a guest, now you're a caller.

Arthur: Yes, I am. I've been negotiating contracts since the [unintelligible 00:28:24] Administration. It used to be back then that health insurance was an afterthought, so it didn't amount to that much. With the financialization of the health insurance industry where they had to make a profit on Wall Street, the results changed considerably and rates skyrocketed. The response from the hospitals was to consolidate and become networks that basically drove private practice doctors and any independent hospitals out of business.

They created their own monopoly within the city limits as well. We're faced with this double profiteering system that of course does not benefit the people of the city of New York. It just benefits the few at the very top. Unless we address that bigger cancer, putting Band-Aids on is not the solution.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, Arthur. Greg, one last thought on this and then we're out of time.

Greg David: The New York City healthcare system has many problems, and especially the ones that you mentioned. As insurance companies got more powerful, hospitals responded by creating these giant networks, whether you're New York-Presbyterian or Montefiore or Northwell. The two of them are engaged in enormous clout negotiations back and forth. It is a system that has many structural problems and is very hard to deal with. There've been many great stories, especially in The Times, about how little charity care nonprofit hospitals provide. I think that's an area people could really look at and really do something about.

Brian Lehrer: After consolidating and acquiring all these hospitals, they sometimes close them if they don't serve the hospitals' finances well enough, to the detriment of the people in the neighborhood. Like the battle that's been going on the Lower East Side regarding Mount Sinai Beth Israel. Right?

Greg David: Yes, but if you looked at the occupancy rates for Mount Sinai Beth Israel, that hospital was not viable. I saw a story. I think a daily occupancy rate was 30%. If we keep hospitals around that have 30% of their beds filled, costs will go up even more.

Brian Lehrer: I told you at the beginning of the segment, folks, that Greg might tick off people on any side of politics [laughs] in New York City. We leave it there with Greg David, business and economics reporter for the news organization THE CITY, and head of the business and economics reporting program at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. Greg's latest article has the damning headline How Adams Played City Budget Numbers, Conjuring a Crisis. Greg, thanks as always.

Greg David: Thank you.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.