( © 2024 NYS Dept. of Economic Development )

What do Post-Its, Spanx, Telfar’s Shopping Bag, and the Accessible Icon symbol have in common? Their revolutionary design. MoMA has organized a new exhibition, Pirouette: Turning Points in Design, which displays products from the museum's collection with unique and memorable design that forever changed our culture. Curator Paola Antonelli discusses the show, on view through October 18.

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. Guess who's coming on the show later this week? Only the most Tony award-winning actor in Broadway history. Audra McDonald, she's currently starring in Gypsy as Rose, delivering a performance in the New York Times calls Stupendously Affecting. Audra McDonald will be my guest on Friday. Later in the show today, we are collaborating with The Moth on a storytelling event and we want to know what's your best story about something that could only have happened here. Get ready to call in and tell us your only a New York story in 60 seconds or less. That's later on in the show. Now let's get this hour started.

[music]

Alison Stewart: A new show at MoMA looks at how design shapes culture and changes how we engage with the world. You'll see the original desktop Macintosh which was basically the first step towards laptops in the home. You'll see the Eames ability to bend plywood for splint and ultimately very expensive chairs. The Post-It Note, the outcome of a mistake. The show spans from the 1930s to the present day. The exhibition is called Pirouette: Turning Points in Design. It opened to the public on Sunday. Museum of Modern Art curator Paola Antonelli is with us. Hi, Paola.

Paola Antonelli: I'm here. Hi, Alison.

Alison Stewart: We are so excited to have you. In fact, we've put some of the designs from this show on our Instagram @allofitwnyc in case anyone wanted to look. What did you think a design needed to have, needed to be to be included in this show?

Paola Antonelli: I bet that some of the masterpieces in the show are on your desk and that's a very important notion. For an object to be in the show, it had to be an object that has had impact either in the past or has has it right now. From the Post-It Note, as you mentioned, to the Sony Walkman the first time you could carry your music and your personal bubble with you to the Frankfurt kitchen by Greta Lihotzky that redesigned the way kitchens are completely laid out. All of these different objects that had impacts either immediately big or small, but reverberating.

Alison Stewart: What do you think all of these designs have in common? What makes them so great?

Paola Antonelli: That if they did not exist, the world would really miss out. Really, that's the only thing. It's always my litmus test. Whenever I see a great piece of design that is worthy of the design collection, before I make the last move, I close my eyes and I think if it didn't exist, would we miss out?

Alison Stewart: Listeners, we want to hear from you during this conversation. I want you to think about this. What is a design that you think had a big impact on your life, on culture as a whole? Give us a call or text us now. 212-433-9692, 212-433-9692. It could be a product you use every day or an invention that really changed how we behave and we've engaged with the world. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. When you talk about would we miss this, would this be missing from our lives, how can great design change our

collective behavior?

Paola Antonelli: You can do it in many different ways. Just think about the Google Map pin. I remember when I moved to the United States and I was living in Los Angeles and the map of LA was a book that was a few inches thick, and so I had to memorize my itinerary every single time. Right now, we tend not to mind ourselves with that because a GPS is going to tell us. That's a direct impact. Or when it comes to the Post-It Note, you mentioned it before, I'm thinking, forget our daily life, but think of workshops. Think of how it's become a way to organize thoughts in a different way.

Truly, I would like people to stop and look at objects and understand deeply what kind of impact they have on our lives. Big, small, positive, negative.

Alison Stewart: Yes, let's talk about the Post-It Note. Invented in the '70s and it has earned a reputation like Kleenex or Band-Aid. They're actually sticky notes, but you have the Post-It Note in the show. How did it come about?

Paola Antonelli: It came about because one scientist at 3M in the 1960s was experimenting with glues, and all of a sudden, he came up with this glue that was made with very, very tiny spheres, and therefore, would not really stick. He thought it was a failure, so he put it on the shelf. Thank God he kept it. He didn't throw it out, but it was on the shelf. A decade later, a colleague was singing in a choir and he wanted to keep the pages in the hymnal. It was a church choir, so he wanted to keep the pages and the bookmarks without letting them fall out from the hymnal. He remembered about this sticky, non-permanent glue, and he decided to try it on his own skin, and then all of a sudden, it was a product.

He presented it to his supervisors at 3M and it became the Post-It Note. See, it's an adage that we've heard many times, almost platitude, but mistakes really should never be discounted as such.

Alison Stewart: My guest is Paola Antonelli, MoMA senior curator and director of research and development. We're speaking about a new MoMA exhibition, Pirouette: Turning Points in Design. It's on view now through October 18th. I also wanted to point out to people the way that it is presented. You have. The walls are red and there's curtains hanging in between each exhibit. Why did you decide wanted to present the show this way?

Paola Antonelli: Because I wanted every single object to get the stage, to get its own stage. Some of these objects are like the Bic pen or the M&Ms or the emojis. We don't usually mind them because they're so and deeply in our lives that we don't even pay attention to them anymore. I wanted people to really stop and the spotlight be on them. Also, every single object has its story narrated either through text or audio or a video, so full attention and focus.

Alison Stewart: Oh, yes, the videos are terrific.

Paola Antonelli: Thank you.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Carrie, calling in from downtown. Hi, Carrie. Thank you so much.

Carrie: Hi.

Alison Stewart: Hi.

Carrie: Oh, thanks for having me. Recently, my bedside lamp, I do a lot of reading in bed, and my bedside lamp just conked out. I eventually got an anglepoise, which is a celebrated British band of long-standing. It's just beautiful. It's an architect's lamp and it's a beautiful color. It just makes me surprisingly happy every time I look at it, [laughter] which I'm frankly mortified by. I recommend them to everyone now.

Alison Stewart: Thank you.

Paola Antonelli: That's wonderful. You know what? The fact that it makes you happy is very important. Some designs are absolutely functional. They're a matter of life or death, but in other cases, delight is as important as anything else. An object that is delightful should not cost more than an object that is an aberration. You know what I'm saying? We should demand that kind of elegance and that kind of attention in the objects that surround us.

Alison Stewart: Hear, hear. Let's talk to Scott from Morristown. Hi, Scott, you're on the air.

Scott: Hi. Yes, thank you for having me on. The thing that actually had the most design thing that had the most impact on my life professionally and as an individual was an Apple Macintosh computer. I was a graphic designer working in an advertising studio and everything they were doing there was old school. They still pasted up everything and sent it out to a printer and all that and I said I'm going to make the leap. I bought a Mac and my God, not only was I able to run an entire agency out of my own house but as you were saying before, it made me happy.

You didn't have to use DOS or whatever that crazy interface was on early computers. You had to be an engineer or computer scientist to know even how to and make it do something for you.

Alison Stewart: Thanks for calling, Scott. Yes, the Macintosh--

Paola Antonelli: I want to talk about that interface. Sorry, I just jump on you. I'm so Italian, I jump on you, but I wanted to say that in the exhibition, we also have the icons for the original Macintosh that made Scott so happy designed by Susan Kare. They're also in the collection.

Alison Stewart: Let's see. The Walker. It was miraculous for my active mom when her mobility declined. The freedom it provides is life-changing. That's Jude from Fairfield County. It says, "I'm an avid homebred baker and my latest favorite design is the Danish dough whisk. It's cool wire on a wooden handle that makes mixing flour and water together, not just easy but joyful, a useful, and a beautiful design." Then we got this one which will make your heart sing. "Hey, WNYC, the ballpoint pen. As an artist, I think about it all the time." Panda from New Jersey, the ballpoint pen is in the exhibition.

Paola Antonelli: Indeed. It's the Bic pen version. Absolutely.

Alison Stewart: The best-selling pen in history. Why do you think that's the case?

Paola Antonelli: I think it's because it really worked. When, when Marcel Bich designed it, he used a tungsten sphere as opposed to the previous iron sphere that was used by Laszlo Biro. That tungsten ball really made the ink flow seamlessly without those terrible knots that you sometimes have. Also, he had a hole in the barrel because the pressure needed to be kept constant so that the ink would flow and a second hole so that if anybody ingested by mistake the pen, they could still be able to breathe. It's really interesting. They think about everything.

Alison Stewart: Also in this exhibit is the Monobloc chair. It's this ubiquitous chair that's also part of its controversy as well. Everybody has seen one on some terrace or backyard somewhere. Who developed it and what was unique about its design?

Paola Antonelli: First of all, it's very funny that this exhibition opened at the same time as Bad Bunn-.

Alison Stewart: Exactly.

Paola Antonelli: -dropping it.

Alison Stewart: On the cover of his album.

Paola Antonelli: It's so funny, all these Instagram posts tagging Bad Bunny. I'm very, very flattered. The monobloc chair had been a dream of designers throughout the 20th century. It was this idea of being able to churn out a chair made of one piece of material pop out. In the 1950s, it became almost feasible because there were thermoplastics that are these little pellets of plastic that you can inject in a mold with high temperature and high pressure. You open the mold and you have the chair, but it's only in the 1970s that this became also scalable, that this became also cost-effective. That's how it all started.

Nobody ever really patented a chair. There was this French designer, Henry Massonnet, that did a chair in the 1970s that was one of the most celebrated, but then after that, it's a family, it's a species, almost, the monoblock chair. They have invaded the world for good and for bad. In some cultures, it's cherished, and people fix it, and it's not easy to fix, but they try. In others, because it is so utilitarian, it is easily discarded. People don't get attached to it. It has become, on the one side, a symbol of real mass production and of accessibility and affordability, and on the other hand, it's also become synonymous with consumerism and almost like a symbol of landfills in the whole world.

Alison Stewart: You'll love these two texts, which will get us to our third mention of the exhibit. This is, "The Ziploc baggie, couldn't live without." Another one says, "Pringles can, no more broken chips." This leads us to the fully built German kitchen. From what I read on the sheet, it says that it was designed for efficiency. How so?

Paola Antonelli: Indeed. It was this woman architect, Grete Lihotzky. The prototype was in Frankfurt. After World War I, there was a big housing crisis in many different cities in Germany, and Frankfurt became almost the laboratory. Grete Lihotzky designed a kitchen that was as efficient as possible. It had a gas stove, it had sinks, it had these beautiful aluminum containers for all the different kinds of spices and produce. It had oak details so they would deal with worms and other parasites. It had linoleum on the floor.

If you see it, really, if you see the drawings and the plans, it really looks like it's a boat. Everything is within your arm's reach. It's really for accessibility, for efficiency, and for standardization as a way to lift everybody in society.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about Pirouette: Turning Points in Design. It's on View at MoMA through October 18th. I'm speaking with curator Paola Antonelli. We'd love to know what design has had a big impact on your life, on the culture as a whole. 212-433-9692, 212-243-3-WNYC. Let's go over to Clothing the New York City, the official, the Bushwick Birkin. We'll talk about the Telfar bag. When he was on the show, he said to us that he wanted a bag that people could afford to buy, that everyone could afford to buy. Let's listen to Telfar.

Telfar Clemens: For me growing up, basically, the clothes that I wanted didn't exist, so I basically had to make them. It's like I've always been attracting women's wardrobes. It's like I wanted a shirt that was a crop top, but I wasn't allowed to buy it because it was in the women's section. When I start to make clothes that fit how I wanted to dress, I just didn't put a gender on it. That's always how I proceeded with my career and what I wanted to make because it's like it's for a person that's like me.

A person that really just wears what they think looks good on them, rather than trying to explain where they got it from, or the women's or the men's section or in between. It's always fine for a woman to wear a man's piece, but it's not okay in the opposite way. Really, I wanted that freedom to exist for my customer.

Alison Stewart: What's unusual about the Telfar bag?

Paola Antonelli: Telfar's motto, which really resonates with me, is, this is not for you, it's for everyone. It's this idea of making these bags available to everybody. There's a little bit of struggle. You have to wait for the drop, and then you have to get the color that you want. There's a secondary market. It has all the implications of luxury bags, but it's affordable. I really love this concept. I love the fact that there's a playfulness and a sense of passion and without any jadedness about it. We acquired for the collection the big size tan bag because it's the first one that really went on the runway, but of course, right now there are so many different colors.

I saw that Telfar also opened a store across the street from my house, which is very funny. It has some other colors that I had never seen and it's become an object of desire for myself too, but I'm just controlling my own impulses.

Alison Stewart: How about Crocs? [laughs]

Paola Antonelli: Crocs. No, Crocs is fascinating. First of all, I have to say, it's one of the best original videos that we made. Sarah Cohen is the video maker at the moment. She did a fabulous job. Crocs are fascinating because they're at the same time super ugly. They've been considered some of the ugliest or the ugliest shoes ever produced in the world, but also utilitarian. Also, even though they're relatively young, they've already had quite a few different parts of life. At some point, everybody hated them. I hate Crocs was a tag and people would cut Crocs online. Then instead, it had a second life when different celebrities like Questlove wore them, and then collaborations with Balenciaga.

It remains at the same time super ugly, but also incredibly attractive by those that consider ugliness not the contrary of beauty, but rather another possibility for formal expression.

Alison Stewart: Let's take some more calls. Let's talk to David from Manhattan. Hi, David. Thank you so much for calling in.

David: Hi. Listen, I'm a designer, background in architecture. I'm also an artist and a cabinet maker. I think that for me, the basic element is the paperclip, the glorious paperclip. The way it's just a simple piece of wire bent in a certain way, understanding the idea of friction and coherence. They're used for many different things. If you ever have to get into your phone or computer, you can bend it and get that little diameter wire in there. The other thing in that realm is the spring clothespin. Those two things show, to me, a basic understanding of design and functionality. I hope there is a separate section honoring the paperclip.

Alison Stewart: [laughs] Thank you so much for calling, David. Let's talk to Jackie. Hi, Jackie. Thank you so much for calling All Of It. You're on the air.

Jackie: Hi. I just want to say I'm not the most boring person in the world, but for me, it's electric toothbrush.

Alison Stewart: The electric toothbrush. Why is that?

Jackie: Just for the very obvious reasons of cleanliness, slack. God, I sound so boring. Slack and also brightness and whiteness. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: You sound okay to me. Thank you for calling, Jackie.

Paola Antonelli: Not boring at all. Please, I agree with all of you.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to John. Hi, John. Thank you so much for calling All Of It.

John: Hi. Thank you. For me, the product that amazes me are the little ring seals on milk and juice containers. To open, you put your finger in the little top ring and you pull out. It's a plastic device and it's just beautiful.

Alison Stewart: Thank you for that tip. My guest is Paola Antonelli. We're talking about MoMA's new exhibition, Pirouette: Turning Points in Design. I wanted to ask you about M&MS.

Paola Antonelli: M&MS are really a fun and interesting also example. M&Ms. Were designed at first by Forest Marsh. Forest Mars is the first M in M&MS. The second M is William Murray. Forest Mars is like the Mars bars and instead, William Murray was the president of Hershey Chocolate. Really, we have this like chocolate aristocracy here, but what happened is that Forest Mars was in Spain during the Civil War, so 1936, '39, more or less. There, he saw the soldiers. They were having in their rations small chocolates that were covered with hard sugar coating that prevented them from melting.

When he came back to the United States, he made his own chocolate pellet prototype, and then he brought the idea to Hershey Chocolate Corporation. In the partnership, Hershey would give the chocolate and instead Mars would produce them and distribute them. His design was patented then in 1941. Originally, the chocolates were packaged in cardboard tubes just like the Spanish one, and were available only to the military during the war, and then they became the sensation that we know today.

Alison Stewart: One of the turn, one of the most important exhibits is on the emoji because that really fundamentally has changed the way we communicate.

Paola Antonelli: Yes, it's so important. Emojis are incredibly important. The set that is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art is the original one from 1998, 1999 that was produced by this Japanese designer, Shigetaka Kurita, that was working for a Japanese telecom company, NTT Docomo. The company wanted to communicate with its customers, so wanted to have this easy way to say what the weather was going to be like or sending illustrations of pictograms, like heart symbol, facial expressions.

Kurita was working on what was available at that time, which was a 12 by 12 pixel grid. Imagine having this squares and having 12 by 12 squares, but if you look at the original set of 176 emojis, and right now, there's more than 3,700, if you look at those 176, they still pretty much contain our world. It's quite interesting because we can never be finished with emojis. Right. I'm sure that even though there are 3,700, we still are missing the one that we really want, but at that time, it already was very concisely complete, the whole series. They really changed the way we communicate. They have added nuance.

There's also Moby Dick that is all translated in emojis, I'm sure you know. It's another type of language that is at the same time exquisitely contemporary, but also ancient because you can also think of ideograms and pictograms that go back in the history of times. Very important turning point, not only in design but in the world.

Alison Stewart: Love this text. The tampon.

Paola Antonelli: The tampon also yes, absolutely. So true.

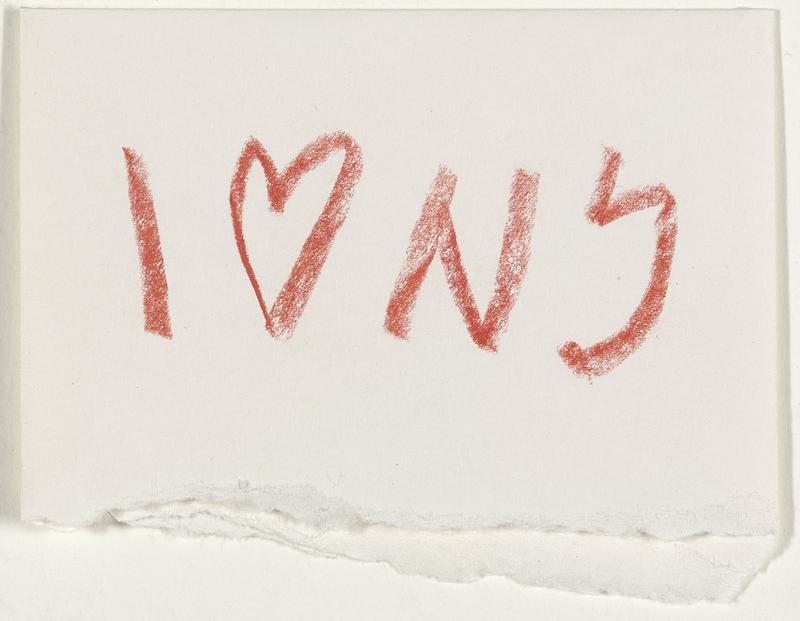

Alison Stewart: There are so many exhibits that you can see throughout this whole exhibition, I should say, but the one I want to finish with is the I heart New York logo conceived by Milton Glaser. You include one of the original sketch designs on an envelope?

Paola Antonelli: Yes. Milton was larger than life, taller than the Empire State Building, and just the most passionate New Yorker you can imagine. It all happened in the 1970s when the governor of New York, the city was in dire straits. There was crime, there was rampant, There was a sanitation workers strike, so everything was going the wrong way. Tourists were not coming anymore and the governor was desperate. He tasked Mary Lawrence Wells, who's this wonderful advertising executive woman that recently died, tasked her with a campaign, and Mary and her team spoke about it with Milton. Milton, so goes the legend, just sketched this I heart and Y on this piece of paper, and he gave it to me.

Whatever the story, the legend is, that's it. That's the piece of paper that I heart New York was born on. Of course, right now, it's been imitated all over the world. For a while, it was completely free to be used by everybody. Then the state of New York started to put some brakes on it, but it still is one of the most recognizable, imitated and universal symbols in the world, logos in the world.

Alison Stewart: You should go see Pirouette: Turning Points in Design at MoMA. I've been speaking with Paola Antonelli. Thank you so much for joining us, Paola

Paola Antonelli: Thank you for having me, Alison.