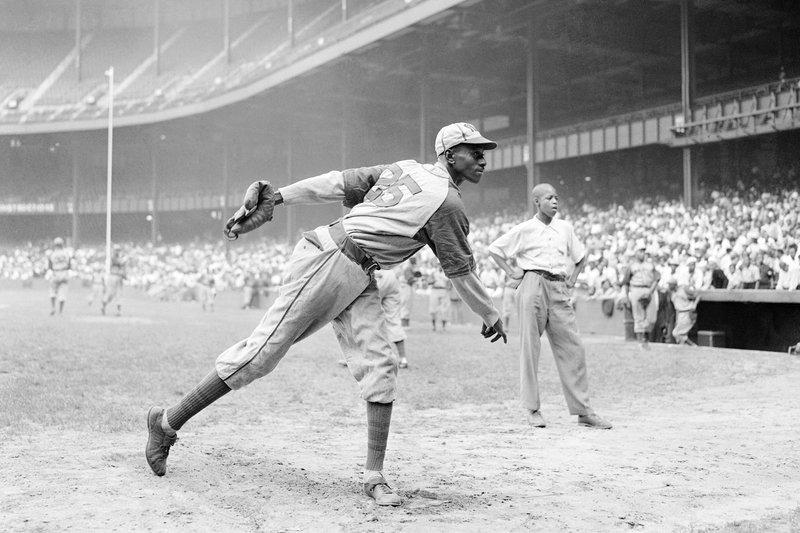

( AP Photo/Matty Zimmerman, File )

"The League," the most recent film from acclaimed documentarian Sam Pollard, tells the story of the Negro Baseball League and how vital it was to the Black community as a whole. He joins to discuss and take your calls.

[music]

Alison Stewart: This is All Of It. I'm Alison Stewart live from the WNYC studios in Soho. Thank you for spending part of your day with us. Whether you're listening on the radio, live streaming, or on demand, I'm grateful you're here. On today's show, we'll talk about the latest season of the podcast, The Last Archive, which goes deep on some obscure New York City history. We have a new concept we're floating out there called small stakes, big opinions. We'll debate Seltzer brands and flavors with Josh Gondelman, who wrote an article in Slate called One Seltzer to Rule Them All, his love letter to Polar. Agree or disagree? You can call it at 1:00 PM. That's our plan. Let's get this started with Sam Pollard and League.

[music]

We have just emerged from the All-Star break for Major League Baseball, the time when the players from the American League and the National League formed two elite squads for one day only. This year, the National League won for the first time in a few years. The first MLB All-Star game took place 90 years ago in 1933, but that same year, another All-Star Baseball game was played, called the East-West Game. It was put together by the Negro League and featured stars like Satchel Paige and Cool Papa Bell, athletes who weren't allowed to play in the All-White Major League.

Thanks to innovative and pioneering business leaders and baseball team owners, the Negro League was formed in 1920. It became a beloved staple in the lives of Black sports fans and the incubator for future Hall of Fame players. It was a significant source of pride and opportunity, and of course, Jackie Robinson began as a player for the all-Black Kansas City Monarchs before signing with the Dodgers and breaking the color line in 1947. The history of the Negro League is chronicled in the new documentary from celebrated filmmaker Sam Pollard. It is called The League, and Sam joins us now. Hi, Sam.

Sam Pollard: Hey, how are you doing, Alison?

Alison Stewart: I'm good. Listeners, we want to hear your experiences with the Negro leagues. Did you have a relative or a family member who attended games or maybe played in the league, maybe yourself have memories of attending a Negro League game? Do you have a favorite Negro League team or team name, maybe like the Birmingham Black Barons or the Jacksonville Redcaps? We want to hear your stories.

Give us a call, 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can also text us at that number or you can call in and join us, 212-433-WNYC. There's so much great archival footage in this film. Where did you start? Where did you go looking for this footage and where did you find it?

Sam Pollard: We had a great archival researcher named Ellen Russell, who really did a deep dive in scouring other archives, personal archives, people who are real Negro League historians who love the game. She was able to cover material, Alison, that I had never even seen before. I thought we wouldn't have enough, but we turned out to have much more than I could ever imagine. Not only archival footage but placards and tickets from the Negro League games. It was a phenomenal amount of material that she was able to locate.

Alison Stewart: As you started looking at the archival footage, what themes started to emerge for you?

Sam Pollard: It was important for me to make sure the audience understood the evolution and the history of the Negro leagues how it started in 1920. It's a little noisy where I'm at so I'll keep talking. It was important for me to understand that 1920, Rube Foster brought together a lot of Negro League owners and said, "We should start our own leagues just like the major leagues." In Kansas City, Missouri, they sat down together and they put together a contract that formed the Negro National League, and it was phenomenal.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk about Andrew Rube Foster, a former pitcher. He owned and managed the Chicago American Giants. First of all, how was Rube Foster as a player? Let's roll all the way back to that.

Sam Pollard: He was a phenomenal player. Many people say he's the one who created the school ball, and we taught it to the major league Hall of Fame with Christie Matterson. He also became a manager of the Chicago American Giants, a Negro League team. He became an owner. He was just a very, very proactive man, and he felt it was important that Negro League owners all come together to create a league that they initially thought could be a way for them to be entering into the major leagues, where major league owners will see all these great players and say, "We should recruit them then." It didn't happen, but that was his dream, that was his hope.

Alison Stewart: Before this happened, though, there were some Black players who played in professional integrated baseball leagues. When was this, and who were some of those standouts?

Sam Pollard: The major standout was a gentleman named Moses Fleetwood Walker, who really was the first African-American to play in the major leagues in the 1880s. Then, Hall of Fame, Cap Anson and a white baseball player in the early 20th century, he didn't want to play with Black players on the field. Basically, the white major league owners created what's called a gentleman's agreement, that they would hire no Black players on their teams.

When I was growing up, I thought Jackie Robinson was the first African-American to play in the major leagues. Then, to learn that Moses Fleetwood Walker was the first was an amazing thing to learn and understand. You can see that the evolution of the Negro leagues, there was such a phenomenal place, like you mentioned, Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Oscar Charleston, Buck Leonard, Buck O'Neill. There was just such a groundswell of great players. By the '40s, after World War II, the Major League realized that some of these players needed to be on Major League Baseball teams.

Alison Stewart: Let's take a call. Gregory from Harlem has a relative who played in the Negro leagues. Hi, Gregory, thank you so much for calling in.

Gregory: Always, Alison. Listen, my uncle Clarence Bruce played for a Pittsburgh team called the Homestead Grays.

Alison Stewart: What position did he play?

Gregory: Second base.

Alison Stewart: What do you remember about him as a player? What do you remember about the Negro leagues?

Gregory: I remember more than anything else that when he wasn't playing baseball, he loved golf. [laughs] He was always standing on the back porch hitting a wiffle golf ball, and he loved him and my father playing golf. I've never seen him play baseball, but he talked about it a lot.

Sam Pollard: How long did he play for the Homestead Grays?

Gregory: I believe he played for three or four seasons. He had just come back from World War II, and so it wasn't very long.

Alison Stewart: Gregory, I love that you have that memory. Thank you for sharing it with us. Listeners, we want to hear your experiences with the Negro leagues. Did you have a relative or a family friend who played in the league? Maybe you remember attending a game. Maybe yourself have memories of the Negro League. We want to hear them. 212-433-9692, 212-433-WNYC. You can text to us at that number. You can also call in and join my conversation with Sam Pollard.

He's director of the league. The documentary is on video on demand now. It was interesting and I'm glad Gregory brought up World War II because when thinking about this team, you also have to think about the moment, the history, what was happening in tandem. The Great Migration seems to have played a role in the Negro leagues. What was the connection between the Great Migration of the early 20th century and the Negro leagues?

Sam Pollard: Well, think about it this way. African Americans are trying to leave the South. They wanted to leave the horrific Jim Crow and the possibility of being lynched. There wasn't enough work. They were sharecropping. They moved to cities like Detroit and Chicago and New York and Dayton, Ohio. When they moved to these cities, they formed their own Black communities. These supposedly segregated Black communities where Black people had to find their own economic structure.

One of the things that helped the economy in these Black communities was these Negro League teams that would play games. They'd bring out fans. They'd have concessions. The money would get circulated back into the Black community. It was a real positive thing on one level, horrific on the other level because we were living during that time with Jim Crow and segregation. Our communities had to figure out how to survive, and they did.

This always gets back to that question, Alison, the pros and cons of integration versus segregation. We know that integration was important on a certain level but what did it do to self-sufficient Black communities? By the time Major League Baseball became integrated, by the time the Civil Rights Movement was really starting to flower, Black communities started to lose their professional people, their doctors, their lawyers, who were able to then leave the communities and integrate to other communities. It had a major economic impact on Black communities.

Alison Stewart: I've just had this conversation with Brian Lehrer around education. It's a tough subject. For those who might be interested, I think it's Hinchliffe Park in Patterson, New Jersey is one of the few old Negro League stadiums that's still standing. It reopened this year for the minor league New Jersey Jackals. It used to be the home of New York Black Yankees. What do we know about the experience of attending one of these games at one of these parks?

Sam Pollard: Well, if you watch the footage, what's amazing to me, Alison, is how Black people, no matter what our adversity we have to deal with in this horrific period of the 20th century, there's such a positive enjoyable sort of let's live our lives. When I'm watching that footage of people in the stands, they're dressed up, they got their Sunday best on. They're loving the game, they're loving seeing people run the bases, hit the ball, steal, bat and run. You can see there's just joy, which you would think that because of all the stuff we've had to face as people of color, it would be less happiness, but you can see it. We had to figure out a way to enjoy our lives and baseball gave people in our communities that opportunity.

Alison Stewart: How was the style of play in the Negro Leagues different from the style of play that was popular at the time in Major League baseball?

Sam Pollard: Well, the style of play was fast. It was aggressive. You had people running the bases, you had people stealing, you had bat and run. It was just a more ecstatic game. If you see the footage of Jackie Robinson from the late '40s and early '50s, you can see him, and when he's about to scope from first to second, his joy. The way he's sort of jumping off the base. Taunting the pitcher.

If you think about the Major League ball players who came after Jackie Robinson, Maury Wills, Ricky Henderson, Reggie Jackson, they brought a real pizazz and enjoyment to the game because before that after Babe Ruth became the home run king, it was really a game of hitting home runs and running around the bases. Black players bought a different kind of energy and a different kind of possess to the game, which made baseball in the '50s and '60s when I grew up very exciting to watch.

Alison Stewart: For those who aren't familiar, what does barnstorming mean when applied to baseball?

Sam Pollard: Well, barnstorming meant that in the '30s, African-American players had the ability to go around from community to community and play local teams to raise some money because they didn't make a lot of money and sometimes the barnstorming meant that Black teams could play white teams. For example, Satchel Paige put together a Black team, and they barnstorm and played against a team that was led by the white pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals, Dizzy Dean. You would go from community to community, you'd pass the hat, raise money, and then let people watch you play baseball.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to Lorraine calling from Eatontown, New Jersey. Hi, Lorraine, thanks for calling All Of It.

Lorraine: Hey, hey, Alison, you're on the air, you're being interviewed. You're interviewing. What a busy day you're having. I'm a listener. Listen, as soon as I heard this conversation, the first thing I wanted to say was Max Manning played for the Newark Eagles. I went to college with and became friends with his daughter, and I still am. She is very involved with the surviving members of the leagues. They have an annual event, I think, in Atlantic City.

She's still involved and still keeping the league alive. That's the first thing. Second thing, you mentioned the stadium in Patterson. Well, you know that there are only two national historic monuments in New Jersey because dedicated to African-Americans. One is Hinchliffe and one is the T. Thomas Fortune House in Red Bank, New Jersey. That stadium is a national historic monument. People need to know that.

Alison Stewart: Lorraine, I love that you listened so closely. I love that you gave us a little bit of history. Thank you so much for calling in, and please keep listening. Please keep calling. Let's talk to Musa, calling in from Newark. Hi Musa, thanks for calling All Of It.

Musa: Hi, Alison. How are you doing?

Alison Stewart: Good, thank you. How are you doing?

Musa: I'm doing good. Doing good. Listen to you every day.

Alison Stewart: Right on.

Musa: My grandfather played for the Kansas City Monarchs and the Birmingham Black Barons. I even have a picture of him with the Kansas City Monarchs uniform that I got from my aunt when I heard that she had it. I really treasure that.

Alison Stewart: What is it you treasure about it?

Musa: Well, it's part of that story. They're from Alabama. I heard that he was a boxer, jazz singer. He played in the Negro Leagues and he was part of the Northern migration. Moving up from Alabama to Chicago and Cleveland and all of the things that our forefathers and foremothers had to do to survive and to find some joy in life.

Alison Stewart: Musa, thank you so much for calling in. Someone texted this question, Sam if you can answer it. Did whites attend Negro League games?

Sam Pollard: I think by the '30s and '40s whites were attending Negro League games. I don't know in terms of their number, but I think they were. White reporters were definitely attending Negro League games, and they were part of the impetus to say, "Maybe people should be considering the integration of the Major Leagues." We know that Black news columnists from the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier, they were always taunting the importance of the Major League looking at Black players and thinking about integrating the league. Wendell Smith was a very important journalist in the Pittsburgh Courier who was always talking about the importance of the integration of the leagues.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about the documentary, the League with its director, Sam Pollard. After the break, we'll talk about one of the pioneering owners and managers who was a woman named Effa Manley. We'll hear a little bit about Josh Gibson and of course, Satchel Paige. We'll take more of your calls as well. Want to hear your remembrances and experiences with the Negro Leagues? 212-433-9692. 212-433-WNYC. We'll meet you right back here after a quick break.

[music]

You're listening to All Of It on WNYC. I'm Alison Stewart. My guest is Sam Pollard. He's the director of the documentary, The League. It's on video on demand now. All about the Negro Leagues, the history of it, the players. Josh Gibson was discovered playing in the Sandlots. What were his greatest strengths as a player, Josh Gibson?

Sam Pollard: He's considered by many next to Babe Ruth on the greatest home run [unintelligible 00:17:12]. In the film, if you compare, is that bat percentage against Hank Aaron and Barry Bonds. It's almost on par. That's how phenomenal he was. The sad thing about Josh Gibson though, Alison, is that by the time Major League Baseball decided to integrate from picking players from the Negro Leagues, he was past his prime and he wasn't mentally very healthy. It's sad that he wasn't able to make the cut. The same thing could be said for Max Manning or Buck Leonard, or Buck O'Neal. These were all great players.

By the time the major leagues decided to start to integrate their teams while these players were passed their prime. He was a great player, just like Satchel Paige, who was considered one of the greatest pitchers who played baseball. Not just Negro League baseball, but that played baseball. Even at the age of, in his early '40s, he did play in the Major Leagues with the Cleveland Indians and helped lead them to a World Series in 1948.

He still was considered a great, great pitcher. There's a story in the film where we say that he would call in the outfield, he had them sit down behind the infield and he would strike out the next three bats with nine strikes. That's how great he was as a pitcher. These were phenomenal players who basically had the opportunity to play on some great Negro league teams, but never got the opportunity to play many of them on Major League teams.

Alison Stewart: How well were they compensated?

Sam Pollard: Nobody in baseball, white or Black, made much money back then. Most of them had part-time jobs afterwards where they barnstormed to make extra money. It wasn't like today where you made millions and make millions and millions of dollars. It wasn't a game where you made money. Hank Aaron even says in the film, when they were playing, they would get a loaf of bread, white bread, peanut butter, and that would be their meals to survive. Satchel Paige, when he got to a certain ballpark, he thought they were going to stay in a hotel. They ended up sleeping out on the field on their suitcases. It wasn't a game about making money, it was about enjoying playing baseball.

Alison Stewart: Musa called back because he wanted to say his grandfather's name. He forgot to say it. It was Charles Langford.

Sam Pollard: Oh, great. Charles Langford.

Alison Stewart: Charles Langford.

Sam Pollard: Max Manning's daughter came to the premier at Tribeca of the Negro League show.

Alison Stewart: Oh, that must have been special.

Sam Pollard: It was special.

Alison Stewart: How did Pittsburgh become a power center of the Negro Leagues?

Sam Pollard: Pittsburgh became a power center because of two men. Cum Posey who owned the Homestead Grays and Gus Greenlee, who owned the Pittsburgh Crawfords. These two men helped rejuvenate the league after Rube Foster's passing in 1930. It was a great steel town. There was a lot of Black people in those communities, like in Homewood, and so they became sort of a fulcrum for the next iteration of the Negro National League in the '30s. They were the ones who came up with the notion of the East-West Classic where you had the best players from the East and the best players from the West playing against each other.

They were powerful teams and they were very successful, particularly the Pittsburgh Crawfords. They had Josh Gibson. They had Satchel Paige. They had Oscar Charleston. They had Cool Papa Bell, but in the late 30s, Trujillo, the president of the Dominican Republic or the dictator of the Dominican Republic wanted to bring a Negro League team to play against local teams in the DR.

He reached out to Satchel Paige, and Satchel Paige basically brought up much of the players from the Pittsburgh Crawfords to play the Dominican Republic, which made the Pittsburgh Crawfords team suffer on the field. It was about money for Satchel and those players. They made a lot of money going to the Dominican Republic and playing baseball there, but that was the real hub in the '30s, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Alison Stewart: Let's talk to-- This is a different Lorraine, but also a Lorraine from New Jersey. Hi Lorraine, thanks for calling in.

Lorraine: Oh, thank you. Several years ago, this was before COVID, Roundabout Theater did a play about a woman who played in the Negro Leagues. I believe her name was Toni Stone. I wonder if your guest could talk a little bit more about women participation, specifically as players.

Alison Stewart: That was a great play. April Matthis played Toni Stone and she was great in that play. [crosstalk]

Sam Pollard: In the 50s, when the Negro Leagues were starting to suffer because they were losing players, they came up with some other things, nice women players like Toni Stone who was a really great player. We only mentioned them very slightly in the film because we ran out of time in terms of how much material we could put in, but there were three or four Negro League women players who are-- If you go to Kansas City to the Negro League Museum, some of these women have plaques in their uniforms from playing in the '50s. One of them played for the Indianapolis, I think, if I'm clear, I think Toni might have played for the Indianapolis Clowns and replaced Hank Aaron.

Alison Stewart: We can say there was one woman who features prominently in your film who is really important to the story of the Negro Leagues is Effa Manley, co-owner with her husband of the Newark Eagles, who was known as the first lady of Black baseball. How did she come to become so powerful and important?

Sam Pollard: Here she is. There's a little bit of a mystery around her because some people say she wasn't Black, she was really white, but she grew up in a Black community. I'm not sure what's true, but she ended up marrying Abe Manley and they became co-owners of the Newark Eagles. She didn't know much about baseball at the beginning, but she became a real fanatical baseball fan. She was extremely supportive of the team.

One of the things we uncovered in doing the research for this film was that the great Branch Rickey, and I'm saying it with quotes--

Alison Stewart: Big old air quotes.

Sam Pollard: Yes, signed Jackie Robinson, but no one knew that he didn't compensate the Kansas City Monics for Jackie Robinson. He didn't compensate the Newark Eagles for Don Newcomb. He didn't compensate the Baltimore Elite Giants for Roy Campanella. When the Negro League owners heard about this, they were very upset. Effa Manley led the charge basically saying, "This wasn't fair. This wasn't right, that white owners wouldn't compensate Negro League owners for the players."

She was able to get Bill Vek who was running the Cleveland Indians at the time to compensate her for the services, Larry Doby, who became the first African American to play in the American League after Jackie Robinson was the first African American to play in the National League. She was a very powerful woman. She's a Black woman who is in the baseball hall of fame, which is extraordinary.

Alison Stewart: We're talking about the film, The League the documentary. Its director, Sam Pollard is my guest. As integration was on the horizon, how did the Black owners and players feel about the prospect of integration in baseball?

Sam Pollard: I would say it was probably a double-edged sword. On the one hand, here we are in the 50s, we have the Montgomery bus boycott, we have Rosa Parks, she wasn't sitting in the back of the bus. We got Dr. King and Fred Shuttlesworth and Ralph Abernathy coming to the floor fighting for we didn't want to be treated as second-class citizens anymore. Any Black person had to feel that was the most positive thing to happen.

On the other hand, it had an impact on economics and of the communities. There were Black communities that were self-sufficient, be it in Harlem, be it in Brownsville, Chicago, be it in Tulsa. These communities suffered because as I said earlier, the Black professionals who were at most times living within the Black communities with other working-class people, when they started to get the opportunity to leave these communities, the communities suffered.

When the Negro League teams started to lose their players, they lost their patrons because their patrons would say, "Well, I don't need to see a Negro League game, I can go watch Willie Mays with the New York Giants. I can go watch Hank Aaron with the Milwaukee Braves. I can watch Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and Don Lukeham with the Brooklyn Dodgers." They started to lose their patrons because now there was an attraction to go to the Major League ballparks and see Major League games.

This notion of America and integration versus segregation is a very complicated kind of story which none of us have a real answer for. It's always complicated being American, particularly a person of color in this country. I can go on all day.

Alison Stewart: Final two questions. One, which logo did you like the best? Because some of the logos are fly of the Negro League baseball hats. Who's a player you wish people knew more about?

Sam Pollard: I like the Kansas City Monarchs logo the best, in my taste. That one I like. To me, it's got a nice interesting look to it. The player that people should know more about, I would say Max Manning. Max Manning is a player, he was a good pitcher, people should know more about him. I didn't know much about him at all since I started the show. I knew about Josh and Satchel and Cool Papa Bell and Buck O'Neal because of Ken Burns, but now I got to learn about Max Manning and Buck Leonard and Oscar Charleston. To me, it was like, "Oh wow, now I can dig deeper into learning about these other players." I didn't really know much about them.

Alison Stewart: The name of the film is The League. Its director is Sam Pollard. It is on video on demand. It's a great, great watch. Sam, thanks for being with us.

Sam Pollard: My pleasure, and I love that little thing about Ella Fitzgerald. She was in a home of detention and then she created that great song, A-Tisket, A-Tasket, a brown and yellow basket. [laughs]

Alison Stewart: That is up next. You did my former promo for me, Sam.

[laughter]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.